Symbolism (movement)

Death and the Grave Digger (La Mort et le Fossoyeur) (c. 1895) by Carlos Schwabe is a visual compendium of symbolist motifs. The angel of Death, pristine snow, and the dramatic poses of the characters all express symbolist longings for transfiguration "anywhere, out of the world". | |

| Years active | from the 1860s |

|---|---|

| Location | France, Belgium, Russia, others |

| Major figures | Charles Baudelaire; Stéphane Mallarmé; Paul Verlaine |

| Influences | Romanticism, Parnassianism, Decadent movement |

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and realism.

In literature, the style originates with the 1857 publication of Charles Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal. The works of Edgar Allan Poe, which Baudelaire admired greatly and translated into French, were a significant influence and the source of many stock tropes and images. The aesthetic was developed by Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine during the 1860s and 1870s. In the 1880s, the aesthetic was articulated by a series of manifestos and attracted a generation of writers. The term "symbolist" was first applied by the critic Jean Moréas, who invented the term to distinguish the Symbolists from the related Decadents of literature and art.

Etymology

[edit]The term symbolism is derived from the word "symbol" which derives from the Latin symbolum, a symbol of faith, and symbolus, a sign of recognition, in turn from classical Greek σύμβολον symbolon, an object cut in half constituting a sign of recognition when the carriers were able to reassemble the two halves. In ancient Greece, the symbolon was a shard of pottery which was inscribed and then broken into two pieces which were given to the ambassadors from two allied city states as a record of the alliance.

Precursors and origins

[edit]Symbolism was largely a reaction against naturalism and realism, anti-idealistic styles which were attempts to represent reality in its gritty particularity, and to elevate the humble and the ordinary over the ideal. Symbolism was a reaction in favour of spirituality, imagination, and dreams.[1] Some writers, such as Joris-Karl Huysmans, began as naturalists before becoming symbolists; for Huysmans, this change represented his increasing interest in religion and spirituality. Certain of the characteristic subjects of the Decadents represent naturalist interest in sexuality and taboo topics, but in their case this was mixed with Byronic romanticism and the world-weariness characteristic of the fin de siècle period.

The Symbolist poets have a more complex relationship with Parnassianism, a French literary style that immediately preceded it. While being influenced by hermeticism, allowing freer versification, and rejecting Parnassian clarity and objectivity, it retained Parnassianism's love of word play and concern for the musical qualities of verse. The Symbolists continued to admire Théophile Gautier's motto of "art for art's sake", and retained – and modified – Parnassianism's mood of ironic detachment.[2] Many Symbolist poets, including Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine, published early works in Le Parnasse contemporain, the poetry anthologies that gave Parnassianism its name. But Arthur Rimbaud publicly mocked prominent Parnassians and published scatological parodies of some of their main authors, including François Coppée – misattributed to Coppée himself – in L'Album zutique.[3]

One of Symbolism's most colourful promoters in Paris was art and literary critic (and occultist) Joséphin Péladan, who established the Salon de la Rose + Croix. The Salon hosted a series of six presentations of avant-garde art, writing and music during the 1890s, to give a presentation space for artists embracing spiritualism, mysticism, and idealism in their work. A number of Symbolists were associated with the Salon.

Movement

[edit]The Symbolist Manifesto

[edit]

Jean Moréas published the Symbolist Manifesto ("Le Symbolisme") in Le Figaro on 18 September 1886 (see 1886 in poetry).[4] The Symbolist Manifesto names Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine as the three leading poets of the movement. Moréas announced that symbolism was hostile to "plain meanings, declamations, false sentimentality and matter-of-fact description", and that its goal instead was to "clothe the Ideal in a perceptible form" whose "goal was not in itself, but whose sole purpose was to express the Ideal."

- Ainsi, dans cet art, les tableaux de la nature, les actions des humains, tous les phénomènes concrets ne sauraient se manifester eux-mêmes; ce sont là des apparences sensibles destinées à représenter leurs affinités ésotériques avec des Idées primordiales.

- (Thus, in this art movement, representations of nature, human activities and all real life events don't stand on their own; they are rather veiled reflections of the senses pointing to archetypal meanings through their esoteric connections.)[4][5]

In a nutshell, as Mallarmé writes in a letter to his friend Henri Cazalis, 'to depict not the thing but the effect it produces'.[6]

In 1891, Mallarmé defined Symbolism as follows, "To name an object is to suppress three-quarters of the delight of the poem, which consists in the pleasure of guessing little by little; to suggest is, that is the dream. It is the perfect use of this mystery that constitutes the symbol: to evoke an object, gradually in order to reveal a state of the soul or, inversely, to choose an object and from it identify a state of the soul, by a series of deciphering operations... There must always be enigma in poetry."[7]

While describing the pre-World War I friendship, which defied the pervasive anti-German sentiment and revanchism of the Belle Époque, between French symbolists Paul Verlaine and Stéphane Mallarmé and young and aspiring German symbolist poet Stefan George, Michael and Erika Metzger have written, "For the Symbolists, the pursuit of 'art for art's sake', was a highly serious – nearly a sacred – function, since beauty, in and of itself, stood for a higher meaning beyond itself. In their ultimate higher striving, the French Symbolists are not far from the Platonic ideals of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, and this idealistic aspect was undoubtedly what appealed to George far more than the Estheticism, the Bohemianism, and the apparent Nihilism so often superficially associated with this group."[8]

Techniques

[edit]

The symbolist poets wished to liberate techniques of versification in order to allow greater room for "fluidity", and as such were sympathetic with the trend toward free verse, as evident in the poems of Gustave Kahn and Ezra Pound. Symbolist poems were attempts to evoke, rather than primarily to describe; symbolic imagery was used to signify the state of the poet's soul. T. S. Eliot was influenced by the poets Jules Laforgue, Paul Valéry and Arthur Rimbaud who used the techniques of the Symbolist school,[9] though it has also been said[by whom?] that 'Imagism' was the style to which both Pound and Eliot subscribed (see Pound's Des Imagistes). Synesthesia was a prized experience; poets sought to identify and confound the separate senses of scent, sound, and colour. In Baudelaire's poem Correspondences (which mentions forêts de symboles ("forests of symbols") and is considered the touchstone of French Symbolism):[10]

- Il est des parfums frais comme des chairs d'enfants,

Doux comme les hautbois, verts comme les prairies,

– Et d'autres, corrompus, riches et triomphants,

Ayant l'expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l'ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l'encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l'esprit et des sens.

- (There are fragrances that are fresh like children's skin,

calm like oboes, green like meadows

– And others, rotten, heady, and triumphant,

having the expansiveness of infinite things,

like amber, musk, benzoin, and incense,

which sing of the raptures of the soul and senses.)

- (There are fragrances that are fresh like children's skin,

- A noir, E blanc, I rouge, U vert, O bleu : voyelles…

- (A black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels…)

– both poets seek to identify one sense experience with another. The earlier Romanticism of poetry used symbols, but these symbols were unique and privileged objects. The symbolists were more extreme, investing all things, even vowels and perfumes, with potential symbolic value. "The physical universe, then, is a kind of language that invites a privileged spectator to decipher it, although this does not yield a single message so much as a superior network of associations."[11] Symbolist symbols are not allegories, intended to represent; they are instead intended to evoke particular states of mind. The nominal subject of Mallarmé's "Le cygne" ("The Swan") is of a swan trapped in a frozen lake. Significantly, in French, cygne is a homophone of signe, a sign. The overall effect is of overwhelming whiteness; and the presentation of the narrative elements of the description is quite indirect:

- Le vierge, le vivace, et le bel aujourd'hui

Va-t-il nous déchirer avec un coup d’aile ivre

Ce lac dur oublié que hante sous le givre

Le transparent glacier des vols qui n’ont pas fui!

Un cygne d’autrefois se souvient que c’est lui

Magnifique mais qui sans espoir se délivre…- (The virgin, lively, and beautiful today –

Will it tear us up with a drunken wingbeat

This hard forgotten lake that lurks beneath the frost,

The transparent glacier of flights not taken with a blow from a drunken wing?

A swan of long ago remembers that it is he

Magnificent but without hope, who breaks free…)

- (The virgin, lively, and beautiful today –

Paul Verlaine and the poètes maudits

[edit]Of the several attempts at defining the essence of symbolism, perhaps none was more influential than Paul Verlaine's 1884 publication of a series of essays on Tristan Corbière, Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, Gérard de Nerval, and "Pauvre Lelian" ("Poor Lelian", an anagram of Paul Verlaine's own name), each of whom Verlaine numbered among the poètes maudits, "accursed poets."

Verlaine argued that in their individual and very different ways, each of these hitherto neglected poets found genius a curse; it isolated them from their contemporaries, and as a result these poets were not at all concerned to avoid hermeticism and idiosyncratic writing styles.[12] They were also portrayed as at odds with society, having tragic lives, and often given to self-destructive tendencies. These traits were not hindrances but consequences of their literary gifts. Verlaine's concept of the poète maudit in turn borrows from Baudelaire, who opened his collection Les fleurs du mal with the poem Bénédiction, which describes a poet whose internal serenity remains undisturbed by the contempt of the people surrounding him.[13]

In this conception of genius and the role of the poet, Verlaine referred indirectly to the aesthetics of Arthur Schopenhauer, the philosopher of pessimism, who maintained that the purpose of art was to provide a temporary refuge from the world of strife of the will.[14]

Philosophy

[edit]Schopenhauer's aesthetics represented shared concerns with the symbolist programme; they both tended to consider Art as a contemplative refuge from the world of strife and will. As a result of this desire for an artistic refuge, the symbolists used characteristic themes of mysticism and otherworldliness, a keen sense of mortality, and a sense of the malign power of sexuality, which Albert Samain termed a "fruit of death upon the tree of life."[15] Mallarmé's poem Les fenêtres[16] expresses all of these themes clearly. A dying man in a hospital bed, seeking escape from the pain and dreariness of his physical surroundings, turns toward his window but then turns away in disgust from

- … l'homme à l'âme dure

Vautré dans le bonheur, où ses seuls appétits

Mangent, et qui s'entête à chercher cette ordure

Pour l'offrir à la femme allaitant ses petits, …

- (… the hard-souled man,

Wallowing in happiness, where only his appetites

Feed, and who insists on seeking out this filth

To offer to the wife suckling his children, …)

- (… the hard-souled man,

and in contrast, he "turns his back on life" (tourne l’épaule à la vie) and he exclaims:

- Je me mire et me vois ange! Et je meurs, et j'aime

– Que la vitre soit l'art, soit la mysticité –

A renaître, portant mon rêve en diadème,

Au ciel antérieur où fleurit la Beauté!

- (I look at myself and I seem like an angel! and I die, and I love

– Whether the mirror might be art, or mysticism –

To be reborn, bearing my dream as a crown,

Under that former sky where Beauty flourishes!)

- (I look at myself and I seem like an angel! and I die, and I love

Symbolists and decadents

[edit]The symbolist style has frequently been confused with the Decadent movement, the name derived from French literary critics in the 1880s, suggesting the writers were self indulgent and obsessed with taboo subjects.[17] While a few writers embraced the term, most avoided it. Jean Moréas' manifesto was largely a response to this polemic. By the late 1880s, the terms "symbolism" and "decadence" were understood to be almost synonymous.[18] Though the aesthetics of the styles can be considered similar in some ways, the two remain distinct. The symbolists were those artists who emphasized dreams and ideals; the Decadents cultivated précieux, ornamented, or hermetic styles, and morbid subject matters.[19] The subject of the decadence of the Roman Empire was a frequent source of literary images and appears in the works of many poets of the period, regardless of which name they chose for their style, as in Verlaine's "Langueur":[20]

- Je suis l'Empire à la fin de la Décadence,

Qui regarde passer les grands Barbares blancs

En composant des acrostiches indolents

D'un style d'or où la langueur du soleil danse.- (I am the Empire at the endgame of decadence, watching the great pale barbarians passing by, all the while composing lazy acrostic poems in a gilded style where the languishing sun dances.)

Periodical literature

[edit]

A number of important literary publications were founded by symbolists or became associated with the style. The first was La Vogue initiated in April 1886. In October of that same year, Jean Moréas, Gustave Kahn, and Paul Adam began the periodical Le Symboliste. One of the most important symbolist journals was Mercure de France, edited by Alfred Vallette, which succeeded La Pléiade; founded in 1890, this periodical endured until 1965. Pierre Louÿs initiated La conque, a periodical whose symbolist influences were alluded to by Jorge Luis Borges in his story Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote. Other symbolist literary magazines included La Revue blanche, La Revue wagnérienne, La Plume and La Wallonie.

Rémy de Gourmont and Félix Fénéon were literary critics associated with symbolism. The symbolist and decadent literary styles were satirized by a book of poetry, Les Déliquescences d'Adoré Floupette, published in 1885 by Henri Beauclair and Gabriel Vicaire.[21]

In other media

[edit]Visual arts

[edit]

Symbolism in literature is distinct from symbolism in art although the two were similar in many aspects. In painting, symbolism can be seen as a revival of some mystical tendencies in the Romantic tradition, and was close to the self-consciously morbid and private decadent movement.

There were several rather dissimilar groups of Symbolist painters and visual artists, which included Paul Gauguin, Gustave Moreau, Gustav Klimt, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, Jacek Malczewski, Odilon Redon, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Henri Fantin-Latour, Gaston Bussière, Edvard Munch, Fernand Khnopff, Félicien Rops, and Jan Toorop. Symbolism in painting was even more widespread geographically than symbolism in poetry, affecting Mikhail Vrubel, Nicholas Roerich, Victor Borisov-Musatov, Martiros Saryan, Mikhail Nesterov, Léon Bakst, Elena Gorokhova in Russia, as well as Frida Kahlo in Mexico,[citation needed] Elihu Vedder, Remedios Varo, Morris Graves and David Chetlahe Paladin in the United States. Auguste Rodin is sometimes considered a symbolist sculptor.

The symbolist painters used mythological and dream imagery. The symbols used by symbolism are not the familiar emblems of mainstream iconography but intensely personal, private, obscure and ambiguous references. More a philosophy than an actual style of art, symbolism in painting influenced the contemporary Art Nouveau style and Les Nabis.[14]

Music

[edit]Symbolism had some influence on music as well. Many symbolist writers and critics were early enthusiasts of the music of Richard Wagner,[22] an avid reader of Schopenhauer.

The symbolist aesthetic affected the works of Claude Debussy. His choices of libretti, texts, and themes come almost exclusively from the symbolist canon. Compositions such as his settings of Cinq poèmes de Charles Baudelaire, various art songs on poems by Verlaine, the opera Pelléas et Mélisande with a libretto by Maurice Maeterlinck, and his unfinished sketches that illustrate two Poe stories, The Devil in the Belfry and The Fall of the House of Usher, all indicate that Debussy was profoundly influenced by symbolist themes and tastes. His best known work, the Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, was inspired by Mallarmé's poem, L'après-midi d'un faune.[citation needed]

The symbolist aesthetic also influenced Aleksandr Scriabin's compositions. Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire takes its text from German translations of the symbolist poems by Albert Giraud, showing an association between German expressionism and symbolism. Richard Strauss's 1905 opera Salomé, based on the play by Oscar Wilde, uses a subject frequently depicted by symbolist artists.

Prose fiction

[edit]Symbolism's style of the static and hieratic adapted less well to narrative fiction than it did to poetry. Joris-Karl Huysmans' 1884 novel À rebours (English title: Against Nature or Against the Grain) explored many themes that became associated with the symbolist aesthetic. This novel, in which very little happens, catalogues the psychology of Des Esseintes, an eccentric, reclusive antihero. Oscar Wilde was influenced by the novel as he wrote Salome, and Huysman's book appears in The Picture of Dorian Gray: the titular character becomes corrupted after reading the book.[23]

Paul Adam was the most prolific and representative author of symbolist novels.[citation needed] Les Demoiselles Goubert (1886), co-written with Jean Moréas, is an important transitional work between naturalism and symbolism. Few symbolists used this form. One exception was Gustave Kahn, who published Le Roi fou in 1896. In 1892, Georges Rodenbach wrote the short novel Bruges-la-Morte, set in the Flemish town of Bruges, which Rodenbach described as a dying, medieval city of mourning and quiet contemplation: in a typically symbolist juxtaposition, the dead city contrasts with the diabolical re-awakening of sexual desire.[24] The cynical, misanthropic, misogynistic fiction of Jules Barbey d'Aurevilly is sometimes considered symbolist, as well. Gabriele d'Annunzio wrote his first novels in the symbolist manner.

Theatre

[edit]

The characteristic emphasis on an internal life of dreams and fantasies have made symbolist theatre difficult to reconcile with more recent trends. Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam's drama Axël (rev. ed. 1890) is a definitive symbolist play. In it, two Rosicrucian aristocrats become enamored of each other while trying to kill each other, only to agree to commit suicide mutually because nothing in life could equal their fantasies. From this play, Edmund Wilson adopted the title Axel's Castle for his influential study of the symbolist literary aftermath.

Maurice Maeterlinck, also a symbolist playwright, wrote The Blind (1890), The Intruder (1890), Interior (1891), Pelléas and Mélisande (1892), and The Blue Bird (1908). Eugénio de Castro is considered one of the introducers of Symbolism in the Iberian Peninsula. He wrote Belkiss, "dramatic prose-poem" as he called it, about the doomed passion of Belkiss, The Queen of Sheba, to Solomon, depicting in an avant-garde and violent style the psychological tension and recreating very accurately the tenth century BC Israel. He also wrote King Galaor and Polycrates' Ring, being one of the most prolific Symbolist theoriticians.[25]

Lugné-Poe (1869–1940) was an actor, director, and theatre producer of the late nineteenth century. Lugné-Poe "sought to create a unified nonrealistic theatre of poetry and dreams through atmospheric staging and stylized acting".[26] Upon learning about symbolist theatre, he never wanted to practice any other form. After beginning as an actor in the Théâtre Libre and Théâtre d'Art, Lugné-Poe grasped on to the symbolist movement and founded the Théâtre de l'Œuvre where he was manager from 1892 until 1929. Some of his greatest successes include opening his own symbolist theatre, producing the first staging of Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi (1896), and introducing French theatregoers to playwrights such as Ibsen and Strindberg.[26]

The later works of the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov have been identified by essayist Paul Schmidt as being much influenced by symbolist pessimism.[27] Both Konstantin Stanislavski and Vsevolod Meyerhold experimented with symbolist modes of staging in their theatrical endeavors.

Drama by symbolist authors formed an important part of the repertoire of the Théâtre de l'Œuvre and the Théâtre d'Art.

Effect

[edit]Black night.

White snow.

The wind, the wind!

It will not let you go. The wind, the wind!

Through God's whole world it blows

The wind is weaving

The white snow.

Brother ice peeps from below

Stumbling and tumbling

Folk slip and fall.

God pity all!

From "The Twelve" (1918)

Trans. Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky[28]

Night, street and streetlight, drug store,

The purposeless, half-dim, drab light.

For all the use live on a quarter century –

Nothing will change. There's no way out.

You'll die – and start all over, live twice,

Everything repeats itself, just as it was:

Night, the canal's rippled icy surface,

The drug store, the street, and streetlight.

"Night, street and streetlight, drugstore..." (1912) Trans. by Alex Cigale

Among English-speaking artists, the closest counterpart to symbolism was aestheticism. The Pre-Raphaelites were contemporaries of the earlier symbolists, and have much in common with them. Symbolism had a significant influence on modernism (Remy de Gourmont considered the Imagists were its descendants)[29] and its traces can also be detected in the work of many modernist poets, including T. S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Conrad Aiken, Hart Crane, and W. B. Yeats in the anglophone tradition and Rubén Darío in Hispanic literature. The early poems of Guillaume Apollinaire have strong affinities with symbolism. Early Portuguese Modernism was heavily influenced by Symbolist poets, especially Camilo Pessanha; Fernando Pessoa had many affinities to Symbolism, such as mysticism, musical versification, subjectivism and transcendentalism.

Edmund Wilson's 1931 study Axel's Castle focuses on the continuity with symbolism and several important writers of the early twentieth century, with a particular emphasis on Yeats, Eliot, Paul Valéry, Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and Gertrude Stein. Wilson concluded that the symbolists represented a dreaming retreat into

things that are dying–the whole belle-lettristic tradition of Renaissance culture perhaps, compelled to specialize more and more, more and more driven in on itself, as industrialism and democratic education have come to press it closer and closer.[30]

This section possibly contains original research. (February 2018) |

After the beginning of the 20th century, symbolism had a major effect on Russian poetry even as it became less and less popular in France. Russian symbolism originally began as an emulation of the French original, but then, under the influence of Vyacheslav Ivanov, it radically diverged until it became something unrecognizable. Steeped in the doctrines of Eastern Orthodoxy and the Christian mystical philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov, it began the careers of several major poets such as Alexander Blok, Andrei Bely, Boris Pasternak, and Marina Tsvetaeva. Bely's novel Petersburg (1912) is considered the greatest example of Russian symbolist prose.

Primary influences on the style of Russian Symbolism were the irrationalistic and mystical poetry and philosophy of Fyodor Tyutchev and Solovyov, the novels of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the operas of Richard Wagner,[31] the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer[32] and Friedrich Nietzsche,[33] French symbolist and decadent poets (such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine and Charles Baudelaire), and the dramas of Henrik Ibsen.

The style was largely inaugurated by Nikolai Minsky's article The Ancient Debate (1884) and Dmitry Merezhkovsky's book On the Causes of the Decline and on the New Trends in Contemporary Russian Literature (1892). Both writers promoted extreme individualism and the act of creation. Merezhkovsky was known for his poetry as well as a series of novels on god-men, among whom he counted Christ, Joan of Arc, Dante, Leonardo da Vinci, Napoleon, and (later) Hitler. His wife, Zinaida Gippius, also a major poet of early symbolism, opened a salon in St Petersburg, which came to be known as the "headquarters of Russian decadence". Andrei Bely's Petersburg (novel) a portrait of the social strata of the Russian capital, is frequently cited as a late example of Symbolism in 20th century Russian literature.

In Romania, symbolists directly influenced by French poetry first gained influence during the 1880s, when Alexandru Macedonski reunited a group of young poets associated with his magazine Literatorul. Polemicizing with the established Junimea and overshadowed by the influence of Mihai Eminescu, Romanian symbolism was recovered as an inspiration during and after the 1910s, when it was exampled by the works of Tudor Arghezi, Ion Minulescu, George Bacovia, Mateiu Caragiale, Tristan Tzara and Tudor Vianu, and praised by the modernist magazine Sburătorul.

The symbolist painters were an important influence on expressionism and surrealism in painting, two movements which descend directly from symbolism proper. The harlequins, paupers, and clowns of Pablo Picasso's "Blue Period" show the influence of symbolism, and especially of Puvis de Chavannes. In Belgium, symbolism became so popular that it came to be known as a national style, particularly in landscape painting:[34] the static strangeness of painters like René Magritte can be considered as a direct continuation of symbolism. The work of some symbolist visual artists, such as Jan Toorop, directly affected the curvilinear forms of art nouveau.

Many early motion pictures also employ symbolist visual imagery and themes in their staging, set designs, and imagery. The films of German expressionism owe a great deal to symbolist imagery. The virginal "good girls" seen in the cinema of D. W. Griffith, and the silent film "bad girls" portrayed by Theda Bara, both show the continuing influence of symbolism, as do the Babylonian scenes from Griffith's Intolerance. Symbolist imagery lived on longest in horror film: as late as 1932, Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr showed the obvious influence of symbolist imagery; parts of the film resemble tableau vivant re-creations of the early paintings of Edvard Munch.[35]

Symbolists

[edit]

Precursors

[edit]- William Blake (1757–1827) English poet and artist (Songs of Innocence)

- Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) German painter (Wanderer above the Sea of Fog)

- Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher (Sartor Resartus)[36]

- Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837) Russian poet and writer (Eugene Onegin)

- Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870) French novelist

- Đorđe Marković Koder (1806–1891) Serbian poet (Romoranka)

- Gérard de Nerval (1808–1855) French poet

- Jules Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly (1808–1889) French writer

- Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) American poet and writer (The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket)

- Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841) Russian poet and writer (A Hero of Our Time)

- Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) French poet (Les Fleurs du mal)

- Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880) French writer (Madame Bovary)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) English poet and painter (Beata Beatrix)

- Christina Rossetti (1830–1894) English poet

Authors

[edit]Armenian

- Misak Metsarents (1886–1908)

- Levon Shant (1869–1951)

- Siamanto (1878–1915)

- Daniel Varujan (1884–1915)

- Vahan Terian (1885–1920)

- Gostan Zarian (1885–1969)

- Diran Chrakian (1885–1921)

- Yeghishe Charents (1897–1937)

Belgian

- Albert Giraud (1860–1929)

- Charles van Lerberghe (1861-1907)

- Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949)

- Albert Mockel (1866–1945)

- Georges Rodenbach (1855–1898)

- Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916)

Czech

- Otokar Březina (1868–1929)

- Viktor Dyk (1877–1931)

- Karel Hlaváček (1874–1898)

- Jiří Mahen (1882–1939)

- Antonín Sova (1864–1928)

Dalmatian

- Ricardo Tironni (1823–1872)

Dutch

- Marcellus Emants (1848-1923)

- Louis Couperus (1863–1923)

- J. H. Leopold (1865–1925)

English

- Edmund Gosse (1849–1928)

- William Ernest Henley (1849–1903)

- Arthur Symons (1865–1945)

- Renée Vivien (1877–1909)

French

- Paul Adam (1862–1920)

- Albert Aurier (1865–1892)

- Léon Bloy (1846–1917)

- Early Henri Barbusse (1873–1935)

- Henri Cazalis (1840–1909)

- Georges Duhamel (1884–1966)

- Paul Fort (1872–1960)

- Rémy de Gourmont (1858–1915)

- Nicolette Hennique (born 1886)

- Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907)

- Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam (1838–1889)

- Alfred Jarry (1873–1907)

- Gustave Kahn (1859–1936)

- Jules Laforgue (1860–1887) Uruguayan (wrote in French)

- Comte de Lautréamont (1846–1870) Uruguayan (wrote in French)

- Jean Lorrain (1855–1906)

- Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898)

- Alexandre Mercereau (1884–1945)

- Oscar Milosz (1877–1939) Lithuanian (wrote in French)

- Jean Moréas (1856–1910) Greek (wrote in French)

- Saint-Pol-Roux (1861–1940)

- Émile Nelligan (1879–1941) Canadian (wrote in Quebec French)

- Germain Nouveau (1851–1920)

- Rachilde (1860–1953)

- Henri de Régnier (1864–1936)

- Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891)

- Jules Romains (1885–1972)

- Albert Samain (1858–1900)

- Marcel Schwob (1867–1905)

- Paul Valéry (1871–1945)

- Paul Verlaine (1844–1896)

- Francis Vielé-Griffin (1863–1937)

- Charles Vildrac (1882–1971)

Georgian

- Valerian Gaprindashvili (1888–1941)

- Paolo Iashvili (1894–1937)

- Sergo Kldiashvili (1893–1986)

- Giorgi Leonidze (1899–1966)

- Kolau Nadiradze (1895–1991)

- Grigol Robakidze (1880–1962)

- Titsian Tabidze (1895–1937)

- Sandro Tsirekidze (1894–1923)

German and Austrian

- Stefan George (1868–1933) German

- Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874–1929) Austrian

- Alfred Kubin (1877–1959) Austrian

- Gustav Meyrink (1868–1932) Austrian

- Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) Austro-Bohemian

- Arthur Schnitzler (1862–1931) Austrian

Irish language

- See also: Modern literature in Irish

- Patrick Pearse (1879–1916)

- Máirtín Ó Direáin (1910–1988)

Polish

- See also: Young Poland movement

- Stanisław Korab-Brzozowski (1876–1901)

- Antoni Lange (1861–1929)

- Tadeusz Miciński (1873–1918)

Portuguese and Brazilian

- Manuel da Silva Gaio (1861–1934)

- João da Cruz e Sousa (1861–1898) Brazilian

- Raul Brandão (1867–1930)

- Alberto Osório de Castro (1868–1946)

- Eugénio de Castro (1869–1944)

- Alphonsus de Guimaraens (1870–1921) Brazilian

- António Nobre (1867–1900)

- Camilo Pessanha (1867–1926)

- Augusto Gil (1873–1929)

- Mário de Sá-Carneiro (1890–1916)

Russian

- Innokenty Annensky (1855–1909)

- Konstantin Balmont (1867–1942)

- Andrei Bely (1880–1934)

- Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

- Alexander Blok (1880–1921)

- Valery Bryusov (1873–1924)

- Georgy Chulkov (1879–1939)

- Zinaida Gippius (1869–1945)

- Vyacheslav Ivanov (1866–1949)

- Fyodor Sologub (1863–1927)

- Vladimir Solovyov[26] (1853–1900)

- Dmitry Merezhkovsky (1865–1941)

- Teffi (1872–1952)

- Maximilian Voloshin (1877–1932)

Scottish Gaelic

- Fr. Allan MacDonald (1859–1905)

- Sorley MacLean (1911–1996)

- Deòrsa Mac Iain Dheòrsa (1915–1984)

Serbian

- Svetozar Ćorović (1875–1919)

- Jovan Dučić (1871–1943)

- Petar Kočić (1877–1916)

- Veljko Petrović (1884–1967)

- Vladislav Petković Dis (1880–1917)

- Sima Pandurović (1883–1960)

- Milan Rakić (1876–1938)

- Isidora Sekulić (1877–1958)

- Jovan Skerlić (1877–1914)

- Borisav Stanković (1876–1927)

- Aleksa Šantić (1868–1924)

Others

- Josip Murn Aleksandrov (1879–1901) Slovene

- George Bacovia (1881–1957) Romanian

- Jurgis Baltrušaitis (1873–1944) Lithuanian

- Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) Argentine

- Mateiu Caragiale (1885–1936) Romanian

- Dimcho Debelyanov (1887–1916) Bulgarian

- Viktors Eglītis (1877–1945) Latvian

- Ady Endre (1877–1919) Hungarian

- Dumitru Karnabatt (1877–1949) Romanian

- Ivan Krasko (1876–1958) Slovak

- Stuart Merrill (1863–1915) American

- Giovanni Pascoli (1855–1912) Italian

Influence in English literature

[edit]English language authors who influenced or were influenced by symbolism include:

- Conrad Aiken (1889–1973)

- Max Beerbohm (1872–1956)

- Christopher Brennan (1870–1932)

- Roy Campbell (1900–1957)

- Hart Crane (1899–1932)

- Olive Custance (1874–1944)

- Ernest Dowson (1867–1900)

- T. S. Eliot (1888–1965)

- James Elroy Flecker (1884–1915)

- John Gray (1866–1934)

- George MacDonald (1824–1905)

- Arthur Machen (1863–1947)

- Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923)

- Edith Sitwell (1887–1964)

- Clark Ashton Smith (1893–1961)

- George Sterling (1869–1926)

- Wallace Stevens (1879–1955)

- Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909)

- Francis Thompson (1859–1907)

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973)[37]

- Rosamund Marriott Watson (1860–1911)

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

- W. B. Yeats (1865–1939)

Symbolist visual artists

[edit]French

- Edmond Aman-Jean (1858–1936)

- Émile Bernard (1868–1941)

- Gaston Bussière (1862–1929)

- Eugène Carrière (1849–1906)

- Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898)

- Maurice Denis (1870-1943)

- Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904)

- Charles Filiger (1863–1928)

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- Charles Guilloux (1866–1946)

- Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer (1865–1953)

- Pierre Félix Masseau (1869–1937)

- Edgar Maxence (1871–1954)

- Gustave Moreau (1826–1898)

- Gustav-Adolf Mossa (1883–1971)

- Alphonse Osbert (1857–1939)

- Armand Point (1861–1932)

- Ary Renan (1857–1900)

- Odilon Redon (1840–1916)

- Alexandre Séon (1855–1917)

Russian

- See also: Russian Symbolism and the Blue Rose group

- Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

- Alexandre Benois (1870–1960)

- Ivan Bilibin (1876–1942)

- Victor Borisov-Musatov (1870–1905)

- Konstantin Bogaevsky (1872–1943)

- Wassily Kandinsky (early works) (1866–1944)

- Mikhail Nesterov (1862–1942)

- Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947)

- Konstantin Somov (1869–1939)

- Viktor Vasnetsov (1848–1926)

- Mikhail Vrubel (1856–1910)

Belgian

- Félicien Rops (1855–1898)

- Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921)

- James Ensor (1860–1949)

- Égide Rombaux (1865–1942)

- Léon Frédéric (1865–1940)

- William Degouve de Nuncques (1867–1935)

- Jean Delville (1867–1953)

- Léon Spilliaert (1882–1946)

Romanian

- Octavian Smigelschi (1866–1912) Austro-Hungarian-born, culturally Romanian

- Mihail Simonidi (1870–1933)

- Lascăr Vorel (1879–1918)

- Apcar Baltazar (1880–1909)

- Ion Theodorescu-Sion (1882–1939)

German

- Eugen Bracht (1842–1921)

- Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach (1851–1913)

- Fritz Erler (1868–1940)

- Ludwig Fahrenkrog (1867–1952)

- Fidus (1868–1948)

- Otto Greiner (1869–1916)

- Ludwig von Hofmann (1861–1945)

- Max Klinger (1857 – July 1920)

- Emil Nolde (1867–1953)

- Max Pietschmann (1865–1952)

- Paul Schad-Rossa (1862–1916)

- Sascha Schneider (1870–1927)

- Clara Siewert (1862–1945)

- Franz von Stuck (1863–1928)

- Hans Unger (1872–1936)

- Oskar Zwintscher (1870–1916)

Swiss

- Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901)

- Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918)

- Carlos Schwabe (1866–1926)

Austrian

- Albin Egger-Lienz (1868–1926)

- Rudolf Jettmar (1869–1939)

- Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

- Alfred Kubin (1877–1959)

- Karl Mediz (1868–1945)

- Richard Müller (1874–1954)

Polish

- Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929)

- Kazimierz Stabrowski (1869–1929)

- Witold Wojtkiewicz (1879–1909)

- Stanisław Wyspiański (1869–1907)

Others

- George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) English

- James A. McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) American

- Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) American

- John William Waterhouse (1849–1917) English

- Luis Ricardo Falero (1851–1896) Spanish

- Ancell Stronach (1901–1981) Scottish

- Jan Toorop (1858–1928) Dutch

- Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) Italian

- Edvard Munch (1863–1944) Norwegian

- Arthur Bowen Davies (1863–1928) American

- Eliseu Visconti (1866–1944) Brazilian

- John Duncan (1866–1945) Scottish

- Early František Kupka (1871–1957) Czech

- Hugo Simberg (1873–1917) Finnish

- Frances MacDonald (1873–1921) Scottish

- Fermín Arango (1874–1962) Spanish-Argentine

- Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911) Lithuanian

- Stevan Aleksić (1876–1923) Serbian

- Felice Casorati (1883–1963) Italian

- Anselmo Bucci (1887–1955) Italian

- Ze'ev Raban (1890–1970) Polish/Israeli

- Beda Stjernschantz (1867—1910) Finnish

Symbolist playwrights

[edit]- Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) German

- Hugo von Hoffmannsthal (1874 - 1929), Austrian

- Federico García Lorca (1898–1936) Spanish

- Fr. Allan MacDonald (1959 - 1904), Scottish Gaelic literature

- Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949) Belgian

- Máirtín Ó Direáin (1910 - 1988), Irish

- Lugné-Poe (1869–1940) French

- Reinhard Sorge (1892 - 1916) German

Composers affected by symbolist ideas

[edit]

|

|

Gallery

[edit]-

Gustav Klimt, Allegory of Skulptur, 1889

-

Jan Toorop, The Three Brides, 1893

-

Hugo Simberg, The Garden of Death, 1896

-

Fernand Khnopff, Incense, 1898

-

Mikhail Vrubel, The Swan Princess, 1900

-

Franz von Stuck, Susanna und die beiden Alten, 1913

-

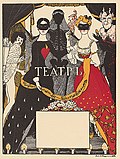

The cover to Aleksander Blok's 1909 book Theatre. Konstantin Somov's illustrations for the Russian symbolist poet display the continuity between symbolism and Art Nouveau artists such as Aubrey Beardsley.

-

Alfred Kubin, The Last King, 1902

-

Franz von Stuck, Die Sünde, 1893

-

Sascha Schneider The Feeling of Dependence, 1920

-

Gustave Moreau, Jupiter and Semele, 1894–95

-

Ferdinand Hodler, The Night, 1889–90

-

Arnold Böcklin – Die Toteninsel I, 1880

-

Jacek Malczewski, Poisoned Well with Chimera, 1905

-

Cesare Saccaggi, La Vetta, (1898)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Balakian, Anna, The Symbolist Movement: a critical appraisal. Random House, 1967, ch. 2.

- ^ Balakian, see above; see also Houston, introduction.

- ^ Album zutique – Wikisource. Gallimard, NRF, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade. 12 February 1965. pp. 111–121.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Jean Moréas, Un Manifeste littéraire, Le Symbolisme, Le Figaro. Supplément Littéraire, No. 38, Saturday 18 September 1886, p. 150, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica

- ^ Jean Moréas, Le Manifeste du Symbolisme, Le Figaro, 1886.

- ^ Conway Morris, Roderick "The Elusive Symbolist movement" – International Herald Tribune, 17 March 2007.

- ^ Edward Hirsch (2017), The Essential Poets Glossary, Mariner Books. Page 314.

- ^ Michael and Erika Metzger (1972), Stefan George, Twayne's World Authors Series. Page 21.

- ^ Untermeyer, Louis, Preface to Modern American Poetry Harcourt Brace & Co New York 1950

- ^ Pratt, William. The Imagist Poem, Modern Poetry in Miniature (Story Line Press, 1963, expanded 2001). ISBN 1-58654-009-2

- ^ Olds, Marshal C. "Literary Symbolism", originally published (as Chapter 14) in A Companion to Modernist Literature and Culture, edited by David Bradshaw and Kevin J. H. Dettmar. Malden, MA : Blackwell Publishing, 2006. Pages 155–162.

- ^ Paul Verlaine, Les Poètes maudits

- ^ Charles Baudelaire, Bénédiction

- ^ a b Delvaille, Bernard, La poésie symboliste: anthologie, introduction. ISBN 2-221-50161-6

- ^ Luxure, fruit de mort à l'arbre de la vie... , Albert Samain, "Luxure", in the publication Au jardin de l'infante (1889)

- ^ Stéphane Mallarmé, Les fenêtres Archived 9 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "What Was the Decadent Movement in Literature? (with pictures)". wiseGEEK. 5 June 2023.

- ^ David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Russian orientalism: Asia in the Russian mind from Peter the Great to the emigration, New Haven: Yale UP, 2010, p. 211 (online).

- ^ Olds, see above, p. 160.

- ^ Langueur, from Jadis et Naguère, 1884

- ^ Henri Beauclair and Gabriel Vicaire, Les Déliquescences d'Adoré Floupette (1885)

Les Déliquescences – poèmes décadents d'Adoré Floupette, avec sa vie par Marius Tapora by Henri Beauclair and Gabriel Vicaire (in French) - ^ Jullian Phillipe, The Symbolists, 1977, p. 8

- ^ "Decadent novel A rebours, or, Against Nature". The British Library. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020.

- ^ Alan Hollinghurst, "Bruges of sighs" (The Guardian, 29 January 2005, accessed 26 April 2009.

- ^ Saraiva, António José; Lopes, Óscar (2017). História da Literatura Portuguesa (17th ed.). Lisboa: Porto Editora. ISBN 978-972-0-30170-3.

- ^ a b c "Symbolism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ The Plays of Anton Chekhov, trans. Paul Schmidt (1997)

- ^ Blok, Alexander; Yarmolinsky, Avrahm; Deutsch, Babette (1929). "The Twelve". The Slavonic and East European Review. 8 (22): 188–198. JSTOR 4202372.

- ^ de Gourmont, Remy. La France (1915)

- ^ Quoted in Brooker, Joseph (2004). Joyce's Critics: Transitions in Reading and Culture. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0299196042.

- ^ "Symbolist Visions; The role of music in the paintings of M. K. Ciurlionis – Nathalie Lorand". lituanus.org.

- ^ Sobolev, Olga (2017). The symbol of the symbolists: Aleksandr Blok in the changing Russian literary canon. Open Book Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 9781783740888. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Boris Christa, 'Andrey Bely and the Symbolist Movement in Russia' in The Symbolist Movement in the Literature of European Languages John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1984, p. 389

- ^ Philippe Jullian, The Symbolists, 1977, p. 55

- ^ Jullian, Philippe, The Symbolists. (Dutton, 1977) ISBN 0-7148-1739-2

- ^ Sencourt, Robert (1971). Adamson, Donald (ed.). T. S. Eliot: A Memoir. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-396-06347-6.

- ^ Lee 2020, Anna Vaninskaya, "Modernity: Tolkien and His Contemporaries", pages 350–366

Further reading

[edit]- Anna Balakian, The Symbolist Movement: a critical appraisal. New York: Random House, 1967

- Michelle Facos, Symbolist Art in Context. London: Routledge, 2011

- Russell T. Clement, Four French Symbolists: A Sourcebook on Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Maurice Denis. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996.

- Bernard Delvaille, La poésie symboliste: anthologie. Paris: Seghers, 1971. ISBN 2-221-50161-6

- John Porter Houston and Mona Tobin Houston, French Symbolist Poetry: An Anthology. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-253-20250-7

- Philippe Jullian, The Symbolists. Oxford: Phaidon; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1973. ISBN 0-7148-1739-2

- Andrew George Lehmann, The Symbolist Aesthetic in France 1885–1895. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1950, 1968

- The Oxford Companion to French Literature, Sir Paul Harvey and J. E. Heseltine (eds.). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959. ISBN 0-19-866104-5

- Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony. London: Oxford University Press, 1930. ISBN 0-19-281061-8

- Arthur Symons, The Symbolist Movement in Literature. E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc. (A Dutton Paperback), 1958

- Edmund Wilson, Axel's Castle: A Study in the Imaginative Literature of 1870–1930. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931 (online version). ISBN 978-1-59853-013-1 (Library of America)

- Michael Gibson, Symbolism London: Taschen, 1995 ISBN 3822893242

- Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal. "Theatre As Church: The Vision of the Mystical Anarchists" in Russian History, 1977, Vol. 4, No. 2 (1977), pp. 122-141. Available Online.

External links

[edit]- Collection of German Symbolist art The Jack Daulton Collection

- Les Poètes maudits by Paul Verlaine (in French)

- ArtMagick The Symbolist Gallery

- What is Symbolism in Art Ten Dreams Galleries – extensive article on Symbolism

- Symbolism Archived 19 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine Gustave Moreau, Puvis de Chavannes, Odilon Redon

- Literary Symbolism Published in A Companion to Modernist Literature and Culture (2006)

![Cesare Saccaggi [it], La Vetta, (1898)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/La_vetta_-_Cesare_Saccaggi.jpg/160px-La_vetta_-_Cesare_Saccaggi.jpg)