Rutan Voyager

| Model 76 Voyager | |

|---|---|

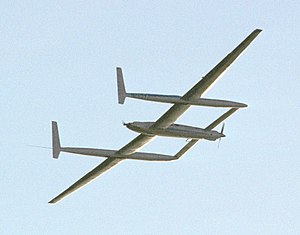

Voyager returning from its flight | |

| General information | |

| Type | Record plane |

| Manufacturer | Rutan Aircraft Factory |

| Designer | |

| Number built | 1 |

| Registration | N269VA |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 1984 |

| First flight | June 22, 1984 |

| Retired | 1987 |

| Preserved at | National Air and Space Museum |

The Rutan Model 76 Voyager was the first aircraft to fly around the world without stopping or refueling. It was piloted by Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager. The flight took off from Edwards Air Force Base's 15,000 foot (4,600 m) runway in the Mojave Desert on December 14, 1986, and ended 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds later on December 23, setting a flight endurance record. The aircraft flew westbound 26,366 statute miles (42,432 km; the FAI accredited distance is 40,212 km)[1] at an average altitude of 11,000 feet (3,350 m).

Design and development

[edit]

The aircraft was first imagined by Burt Rutan and his brother Dick Rutan in 1980.[2] Burt sketched his concept for the aircraft for Dick and Jeana Yeager during a lunch in 1981.[3] The idea was sketched out on the back of a napkin. Voyager was built in Mojave, California over a period of five years, mainly by volunteers working under both the Rutan Aircraft Factory and an organization named Voyager Aircraft. Burt Rutan served as the lead designer for the project, and the chief aerodynamicist was John Roncz.[4]

The airframe made of fiberglass, carbon fiber, and Kevlar weighed 939 pounds (426 kg) when empty. With the engines included, the unladen weight of the plane was 2,250 pounds (1,020 kg). When it was fully loaded with fuel for its historic flight it weighed 9,694.5 pounds (4,397.4 kg).[5] The aircraft had an estimated lift-to-drag ratio (L/D) of 27.[6] The canard and wing airfoils were custom-designed, and the aircraft was analyzed using computational fluid dynamics.[7] Vortex generators were added to the canard to reduce sensitivity to surface contamination by rain.[8]

Voyager had front and rear propellers, powered by separate engines. It was originally flown on June 22, 1984, powered by Lycoming O-235 engines with fixed-pitch propellers.[9] In November 1985, the aircraft was rolled out, fitted with world-flight engines, an air-cooled Teledyne Continental O-240 in the forward location and a liquid-cooled Teledyne Continental IOL-200 in the aft location.[10] Both were firstly fitted with wooden, variable-pitch electrically actuated MT-Propellers.[11] The plan was for the rear engine to be operated throughout the flight. The front engine was intended to provide additional power for takeoff and the initial part of the flight under heavy load.

On July 15, 1986, Dick Rutan and Yeager completed a test flight off the coast of California, in which they flew for 111 hours and 44 minutes, traveling 11,857 statute miles (19,082 km) in twenty circuits between San Luis Obispo and Stewarts Point,[12][13] breaking the previous record held since 28 May 1931 by a Bellanca CH-300 fitted with a Packard DR-980 diesel engine, piloted by Walter Edwin Lees and Frederic Brossy which had set a record by staying aloft for 84 hours and 32 minutes without being refueled. The first attempt at the Voyager test flight was ended by the failure of a propeller pitch-change motor that resulted in an emergency landing at Vandenberg Air Force Base.[14] On a test flight on September 29, 1986, the airplane had to make an emergency landing due to a propeller blade departing the aircraft.[15] As a result, the decision was made to switch to aluminium Hartzell hydraulically actuated propellers.[16] In a crash program, Hartzell made custom propellers for the aircraft, which were first flown on November 15, 1986.[17][18]

World flight

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Voyager's world flight takeoff took place on the longest runway at Edwards AFB at 8:01 am local time on December 14, 1986, with 3,500 of the world's press in attendance.[19] As the plane accelerated, the tips of the wings, which were heavily loaded with fuel, were damaged as they unexpectedly flew down and scraped against the runway, ultimately causing pieces (winglets) to break off at both ends (the pilot had wanted to gain enough speed for the inner wings, rather than the fragile outer wings, to lift the plane; in 67 test flights, the plane had never been loaded to capacity). The aircraft accelerated very slowly and needed approximately 14,200 feet (2.7 mi; 4.3 km) of the runway to gain enough speed to lift from the ground, the wings arching up dramatically just before take-off. The two damaged winglets remained attached to the wings by only a thin layer of carbon fiber and were removed by flying the Voyager in a slip, which introduced side-loading, tearing the winglets off completely. Some of the carbon fiber skin was pulled off in the process, exposing the blue foam core. Burt Rutan following with pilot Mike Melvill determined that Voyager was still within its performance specifications despite the damage and decided to allow the flight to continue. During the flight, the two pilots had to deal with extremely cramped quarters. To reduce stress, the two had originally intended to fly the plane in three-hour shifts, but flight handling characteristics while the plane was heavy prevented routine changeovers, and they became very fatigued. Dick Rutan reportedly stayed at the controls without relief for almost the first three days of the flight.

The plane also continuously reminded the pilots of its pitch instability and fragility. They had to maneuver around bad weather numerous times, most perilously around the 600-mile-wide (1,000 km) Typhoon Marge.[20] Libya denied access to the country's airspace in response to Operation El Dorado Canyon earlier that year. There were contentious radio conversations between the Rutan brothers as Dick flew around weather and, at one time, turned around and began doubling back. As they neared California to land, a fuel pump failed and had to be replaced with its twin pumping fuel from the other side of the aircraft.

In front of 55,000 spectators and a large press contingent, including 23 live feeds breaking into scheduled broadcasting across Europe and North America, the plane safely came back to earth, touching down at 8:06 a.m. at the same airfield 9 days after take-off. Rutan made three low passes over the landing field before putting Voyager down. The average speed for the flight was 116 miles per hour (187 km/h). There were 106 pounds (48 kg) of fuel remaining in the tanks,[5] only about 1.5% of the fuel they had at take-off.

Sanctioned by the FAI and the AOPA, the flight was the first successful aerial nonstop, non-refueled circumnavigation of the Earth that included two passes over the Equator (as opposed to shorter ostensible "circumnavigations" circling the North or South Pole). This feat has since been accomplished only one other time, by Steve Fossett in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer (also designed by Rutan). For the feat, Yeager, the Rutans, and crew chief/builder Bruce Evans received the 1986 Collier Trophy.[21]

Specifications

[edit]

Data from NASM [5]

General characteristics

- Crew: two

- Length: 29 ft 2 in (8.89 m)

- Wingspan: 110 ft 8 in (33.73 m)

- Height: 10 ft 3 in (3.12 m)

- Wing area: 363 sq ft (33.7 m2)

- Airfoil: Roncz 1046 (root), Roncz 1080 (tip), 1082/1082T (canard)[22]

- Empty weight: 2,250 lb (1,021 kg)

- Gross weight: 9,694.5 lb (4,397 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Teledyne Continental O-240 4-cylinder horizontally-opposed engine, 130 hp (97 kW) (front engine)

- Powerplant: 1 × Teledyne Continental IOL-200 4-cylinder horizontally-opposed engine, 110 hp (82 kW) (rear engine)

- Propellers: 2-bladed

Performance

- Maximum speed: 122 mph (196 km/h, 106 kn)

- Range: 24,986 mi (40,212 km, 21,712 nmi)

- Endurance: 216 hours

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Official FAI database". Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- ^ "Scaled Composites/Rutan Voyager Partial Replica". eaa.org. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Voyager Slides, Chapter 01: Voyager Chronology, a Brief Overview". dmc.tamuc.edu. Archived from the original on March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "John Roncz, Master Aerodynamicist To Experimental Aircraft, Flies West". AVweb. Firecrown. October 5, 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Rutan Voyager – Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Archived 2018-07-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ David Noland, "Steve Fossett and Burt Rutan's Ultimate Solo: Behind the Scenes", Popular Mechanics, Feb. 2005 (web version Archived 2006-12-11 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Lednicer, David, "A VSAERO Analysis of Several Canard Configured Aircraft", SAE paper 881485, presented at the SAE Aerospace Technology Conference and Exposition, Anaheim, California, October 1988.

- ^ Bragg, M. B. and Gregorek, G. M., "An Experimental Study of a High Performance Canard Airfoil with Boundary Layer Trip and Vortex Generators", AIAA Paper No. 86-0781-CP, The 14th Aerodynamic Testing Conference Publication, March 1986.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 107.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 121.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 124.

- ^ "Aerospace World". Air Force Magazine. Vol. 69, no. 3. September 1986. p. 43.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 181.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 66.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 198.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 209.

- ^ Yeager, Rutan & Patton 1987, p. 213.

- ^ Roncz, John G., "Propeller Development for the Rutan Voyager", SAE paper 891034, presented at the SAE General Aviation Aircraft Meeting & Exposition, Wichita, Kansas, April 1989.

- ^ Norris 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1987). Chapter 3: Northwest Pacific and North Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones Archived 2011-06-07 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2007-12-19.

- ^ Larson, George C. (January 2012). "From Point A to Point A". Air & Space Smithsonian., p. 84.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- David H. Onkst. Dick Rutan, Jeana Yeager, and the Flight of the Voyager. U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission.

- Stengel, Richard; Brown, Scott (December 29, 1986). "Flight of Fancy". Time. Mojave. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008.

- Norris, Jack (1988). Voyager The World Flight; The Official Log, Flight Analysis and Narrative Explanation. Northridge, California. ISBN 0-9620239-0-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Yeager, Jeana; Rutan, Dick; Patton, Phil (1987). Voyager. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopg. ISBN 1-885283-24-5.

External links

[edit] Media related to Rutan Voyager at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rutan Voyager at Wikimedia Commons- Flight path