A Woman of No Importance

A Woman of No Importance by Oscar Wilde is "a new and original play of modern life", in four acts, first given on 19 April 1893 at the Haymarket Theatre, London.[1] Like Wilde's other society plays, it satirises English upper-class society. It has been revived from time to time since his death in 1900, but has been widely regarded as the least successful of his four drawing room plays.

Background and first production

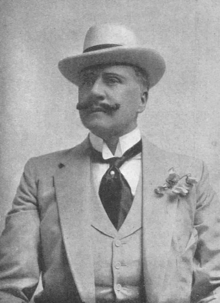

[edit]Wilde's first West End drawing room play, Lady Windermere's Fan, ran at the St James's Theatre for 197 performances in 1892.[2] He briefly moved away from the genre to write his biblical tragedy Salome, after which he accepted a request from the actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree for a new play for Tree's company at the Haymarket Theatre.[3] Wilde worked on it while staying in Norfolk in the summer, and later in a rented flat in St James's, impeded by constant interruptions by Lord Alfred Douglas.[4]

Tree accepted the finished play in October 1892.[5] The leading female role, Mrs Arbuthnot, was intended for Madge Kendal, but for contractual reasons she withdrew and was replaced by Mrs Bernard Beere.[6] The play was first performed on 19 April 1893 at the Haymarket Theatre, London, to an audience that included Arthur Balfour and Joseph Chamberlain;[7] the Prince of Wales attended the second night.[8] The production ran for 113 performances, closing on 16 August.[9]

Original cast

[edit]

- Lord Illingworth – Herbert Beerbohm Tree

- Sir John Pontefract – E. Holman Clark

- Lord Alfred Rufford – Ernest Lawford

- Mr Kelvil, MP – Charles Allan

- The Ven Dr Daubeny, DD (Rector of Wrockley) – Henry Kemble

- Gerald Arbuthnot – Fred Terry

- Farquhar (butler) – — Hay

- Francis (footman) J. Montagu

- Lady Hunstanton – Rose Leclercq

- Lady Caroline Pontefract – R. G. Le Thière

- Lady Strutfield – Blanche Horlock

- Mrs Allonby – Mrs H. B. Tree

- Hester Worsley – Julia Neilson

- Alice (maid) – — Kelly

- Mrs Arbuthnot – Mrs Bernard Beere

- Source: The London Stage.[9]

Plot

[edit]The play is set in "the present" (i.e. 1893).

Act I

[edit]- The Terrace at Hunstanton Chase

The play opens with a party on a terrace in Lady Hunstanton's estate. The upper class guests spend the better part of Act I exchanging social gossip and small talk. Lady Caroline Pontefract patronises an American visitor, Hester Worsley, and proceeds to give her own opinion of everyone in the room (and her surrounding life). Lady Caroline also denounces Hester's enthusiasm for Gerald Arbuthnot until Gerald himself enters to proclaim that Lord Illingworth, a powerful, flirtatious male political figure, intends to take him under his wing as secretary. This is great news for Gerald, as being Lord Illingworth's secretary would be the young man's first step to a life of financial/political success. The guests then discuss the rumours surrounding Lord Illingworth's aim for being a foreign ambassador, while Lady Hunstanton sends a letter through her footman to Gerald's mother, inviting her to the party.

Gerald offers to take Hester for a walk, leaving the remaining guests to gossip further about their social lives. Lady Hunstanton and Lady Stutfield comment on the yet unseen Lord Illingworth's amoral qualities towards women when the man himself enters the terrace. He declines their thanks for his hiring of Gerald Arbuthnot and says that he hired him out of personal interest. Lord Illingworth remains near Mrs Allonby during the entire exchange until the two of them leave for the conservatory together, following a discussion of Hester's background and wealthy father. A footman enters with a letter from Mrs Arbuthnot, stating that she will come to the party after dinner. When Illingworth and Mrs Allonby return, the remaining guests have already moved to have tea in another room. The two characters have a witty conversation involving marriage and women and men until Gerald and Hester enter the room. They have some short small talk, and Lord Illingworth and Mrs Allonby are again left alone. Their discussion turns toward Hester when Mrs Allonby reprehends the young American for her casual talk of being eighteen and a Puritan. Lord Illingworth expresses that he rather admires Hester's beauty and actually uses the conversation to assert his flirtations toward Mrs Allonby, claiming that he has never met a woman so puritanical as Hester that she would steadfastly resist all and any advances. Mrs Allonby asserts that Hester is sincere in her desire to be left alone, but Illingworth interprets her remarks as a playful challenge. Lord Illingworth notices Mrs Arbuthnot's letter lying on a table and remarks that the handwriting on the envelope seems familiar. When Mrs Allonby asks who the handwriting reminds him of, he carelessly mentions "a woman of no importance."[10]

Act II

[edit]- Drawing room at Hunstanton

Gerald's mother arrives at the end of an argument between Hester and the upper-class women. Lord Illingworth enters shortly after, and Gerald uses the opportunity to introduce him to Mrs Arbuthnot. The three share an uncomfortable exchange, as Mrs Arbuthnot (to Gerald's dismay) can only partially express her disapproval of Illingworth's offer. Lord Illingworth excuses himself, and Lady Hunstanton calls everyone into her music-room soon after. Illingworth, however, asks to remain behind to speak with Mrs Arbuthnot.

What follows is the revelation that Gerald is the illegitimate child of Mrs Arbuthnot and Lord Illingworth, once known as George Harford. Years ago, Mrs Arbuthnot and George Harford conceived a child, yet Harford refused to marry Arbuthnot. Harford had offered to provide financial security through his mother, but according to Mrs Arbuthnot, it was his refusal to marry that forced her to leave him and live an arduous life as a scandalous single mother. Mrs Arbuthnot retains a strong bitterness toward Illingworth, yet also begs him to leave her son alone, expressing that after twenty years of being a mother, Gerald is all she has. She refuses to allow Gerald to stay with his father, but Illingworth questions how she will force Gerald to do what she wants. He tells Mrs Arbuthnot that Gerald should be able to choose his own future. Gerald then enters, and Lord Illingworth assures him and his mother that Gerald has the highest qualities that the man had hoped for in a secretary. Illingworth demands any other reason for Mrs Arbuthnot to protest against Gerald's opportunity. Unwilling to reveal her son's true heritage, Mrs Arbuthnot says that she has no other reason.[11]

Act III

[edit]- The Hall at Hunstanton Chase

Act III opens with Gerald and Lord Illingworth talking about Mrs Arbuthnot. Gerald speaks of his admiration and protective attitude toward his mother, expressing that she is a great woman and wondering why she has never told him of his father. Lord Illingworth agrees that his mother is a great woman, but he further explains that great women have certain limitations that inhibit the desires of young men. Leading the conversation into a cynical talk about society and marriage, Lord Illingworth says that he has never been married and that Gerald will have a new life under his wing. Soon the other guests enter, and Lord Illingworth entertains them with his invigorating views on a variety of subjects, such as comedy and tragedy, savages, and world society. Everything Lord Illingworth has to say opposes the norm and excites his company, leaving Mrs Arbuthnot room to say that she would be sorry to hold his views. During a discussion of sinful women, she also opposes Lady Hunstanton's later opinion by saying that ruining a woman's life is unforgivable. When Lady Hunstanton's company finally breaks up, Lord Illingworth and Mrs Allonby leave to look at the Moon. Gerald attempts to follow, but his mother protests and ask him to take her home. Gerald says that he must first say goodbye to Lord Illingworth and also reveals that he will be going to India with him at the end of the month.

Mrs Arbuthnot is then left alone with Hester, and they resume the previous conversation about women. Mrs Arbuthnot is disgusted by Hester's view that the sins of parents are suffered by their children. Recognising that Mrs Arbuthnot is waiting for her son to return, Hester decides to fetch Gerald. Gerald soon returns alone, however, and he becomes frustrated with his mother's continued disapproval for what he sees as an opportunity to earn his mother's respect and the love of Hester. Remembering Hester's views, Mrs Arbuthnot decides to tell her son the truth about his origin and her past life with Lord Illingworth, but she does so in the third person, being sure to describe the despair that betrayed women face. Gerald remains unmoved, however, so Mrs Arbuthnot withdraws her objections. Hester then enters the room in anguish and flings herself into Gerald's arms, exclaiming that Lord Illingworth has "horribly insulted" her. He has apparently tried to kiss her. Gerald almost attacks Illingworth in a rage when his mother stops him the only way she knows how: by telling him that Lord Illingworth is his father. With this revelation, Gerald takes his mother home, and Hester leaves on her own.[12]

Act IV

[edit]- Sitting room in Mrs Arbuthnot's House at Wrockley

Act IV opens with Gerald writing a letter in his mother's sitting room, the contents of which will ask his father to marry Mrs Arbuthnot. Lady Hunstanton and Mrs Allonby are shown in, intending to visit Mrs Arbuthnot. The two comment on her apparent good taste and soon leave when the maid tells them that Mrs Arbuthnot has a headache and will not be able to see anyone. Gerald says that he has given up on being his father's secretary, and he has sent for Lord Illingworth to come to his mother's estate at 4 o'clock to ask for her hand in marriage. When Mrs Arbuthnot enters, Gerald tells her all that he has done and that he will not be his father's secretary. Mrs Arbuthnot exclaims that his father must not enter her house, and the two argue over her marrying Gerald's father. Gerald claims that the marriage is her duty, while Mrs Arbuthnot retains her integrity, saying that she will not make a mockery of marriage by marrying a man she despises. She also tells of how she devoted herself to the dishonour of being a single mother and has given her life to take care of her son. Hester overhears this conversation and runs to Mrs Arbuthnot. Hester says she has realised that the law of God is love and offers to use her wealth to take care of the man she loves and the mother she never had. After ensuring that Mrs Arbuthnot must live with them, Gerald and Hester leave to sit in the garden.

The maid announces the arrival of Lord Illingworth, who forces himself past the doorway and into the house. He approaches Mrs Arbuthnot, telling her that he has resolved to provide financial security and some property for Gerald. Mrs Arbuthnot merely shows him Gerald and Hester in the garden and tells Lord Illingworth that she no longer needs help from anyone but her son and his lover. Illingworth then sees Gerald's unsealed letter and reads it. Lord Illingworth claims that while it would mean giving up his dream as a foreign ambassador, he is willing to marry Mrs Arbuthnot to be with his son. Mrs Arbuthnot refuses to marry him and tells Lord Illingworth that she hates him, adding that her hate for Illingworth and love for Gerald sharpen each other. She also assures Lord Illingworth that it was Hester who made Gerald despise him. Lord Illingworth then admits his defeat with the cold notion that Mrs Arbuthnot was merely his plaything for an affair, calling her his mistress. Mrs Arbuthnot then slaps him with his own glove before he can call Gerald his bastard.

Lord Illingworth, dazed and insulted, gathers himself and leaves after a final glance at his son. Mrs Arbuthnot falls onto the sofa sobbing. When Gerald and Hester enter, she cries out for Gerald, calling him her boy, and then asks Hester if she would have her as a mother. Hester assures her that she would. Gerald sees his father's glove on the floor, and, when he asks who has visited, Mrs Arbuthnot replies, "A man of no importance."[13]

Production history

[edit]

A production toured the British provinces in the latter part of 1893, with a cast headed by Lewis Waller as Lord Illingworth.[14] After the first London run, the play was next seen in the West End when Tree staged a revival at His Majesty's Theatre. The production ran for 45 performances from 22 May 1907; Tree again played Illingworth, Marion Terry played Mrs Arbuthnot, and the cast included Kate Cutler, Viola Tree, Charles Quartermaine and Ellis Jeffreys.[15] The Liverpool Playhouse company presented the play during a London season in 1915.[16] A revival at the Savoy Theatre in 1953 was, in the view of the critic J. C. Trewin, marred by cuts and inauthentic additions to Wilde's text; Clive Brook was Illingworth and the cast included Athene Seyler, Jean Cadell, Isabel Jeans and William Mervyn.[17] There were revivals at the Vaudeville Theatre, London (1967), the Chichester Festival (1978), the Abbey Theatre, Dublin (1996), the Barbican, London (1991) and the Haymarket (2003).[18][19] A revival at the Vaudeville in 2017, starring Dominic Rowan and Eve Best, ran from October to December.[20]

The Internet Broadway Database records two New York productions of A Woman of No Importance. Maurice Barrymore and Rose Coghlan played Illingworth and Mrs Arbuthnot in an 1893–94 production, and Holbrook Blinn and Margaret Anglin starred in the roles in 1916.[21] Robert Brough and his company presented the first Australian production in 1897.[22] Les Archives du spectacle record no performances of the play in France, in contrast with Wilde's other three drawing room plays, which have all been staged in translation on various occasions.[23]

Critical reception

[edit]The play was well received by the public, running from April to August 1893 – considered a good run for its time[n 1] – but received mixed reviews. The reviewer in The Theatre thought it "Not a play, but a stodge of Wilde, leavened by a pinch of human nature", redeemed only by superb acting that "performs a miracle and provides compensation well-nigh sufficient for the disappointments of the play".[25] The Era said, "If Lady Windermere's Fan showed us Mr Oscar Wilde as a playwright at his best, A Woman of No Importance exhibits all the vices of his method with irritating clearness".[26] The Pall Mall Gazette complained of "much want of originality in matter, and some want of originality in manner", but thought it "a play with many strong situations, with much – indeed with too much – amusing dialogue".[27] The Times commented:

Reviewing the play in 1934, W. B. Yeats quoted Walter Pater's comment that Wilde "wrote like an excellent talker"; Yeats agreed and found the verbal wit delightful, but the drama falling back on popular stage conventions.[29] Reviewing a 1953 production, J. C. Trewin wrote, "This revival proved once more that Wilde wrote one sustained play and one only: The Importance of Being Earnest. Nothing else, I fear, matters".[17] Wilde's biographer Richard Ellmann has described A Woman of No Importance as the "weakest of the plays Wilde wrote in the Nineties".[30] After a 1991 revival, The Times called the play "as fatuous a melodrama as ever eminent playwright penned".[18] In 1997, Wilde's biographer Peter Raby commented:

Adaptations

[edit]The play has been adapted for the cinema in at least four versions: British (1921), German (1936), French (1937) and Argentine (1945). The BBC has broadcast six adaptations of the play: one for television (1948) and five for radio (1924, 1949, 1955, 1960 and 1992).[32] A 1960 television adaptation broadcast by Independent Television starred Griffith Jones and Gwen Watford as Illingworth and Mrs Arbuthnot.[33]

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Who's Who in the Theatre an average of 12 new productions a year ran in the West End for more than 100 productions in the decade 1890–1899, including plays, operettas, burlesques and other genres.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Wilde (1966), p. 76

- ^ Wearing (1976), p. 195

- ^ Ellmann, p. 358

- ^ Wilde (1964), p. 56

- ^ Ellmann, p. 356

- ^ "Theatrical Notes", Westminster Gazette, 14 August 1893, p. 3

- ^ Ellermann, p. 360

- ^ "Court Circular", The Times, 21 April 1893, p. 5

- ^ a b Wearing (1976), p. 310

- ^ Wilde (1966), pp. 79–94

- ^ Wilde (1966), pp. 95–113

- ^ Wilde (1966), pp. 114–128

- ^ Wilde (1966), pp. 129–144

- ^ "'A Woman of No Importance' On Tour", The Sketch, 6 September 1893, p. 8

- ^ Wearing (1981), p. 562

- ^ "Kingsway Theatre", Westminster Gazette 11 May 1915, p. 3

- ^ a b Trewin, J. C. "At the Theatre", The Sketch, 25 February 1953, p. 148

- ^ a b Nightingale, Benedict. "Gorgeous but fatuous Wilde", The Times, 3 October 1991, p. 20

- ^ Billington, Michael. "Oscar Wilde at his weakest", The Times, 29 November 1967, p. 11; "Chichester's A Woman of No Importance", The Times, 3 May 1978, p. 5; Clancy, Luke. "Flat champagne", The Times, 17 June 1996, p. 18; and Nightingale, Benedict. "A lifeless lesson in pretty wit", The Times, 17 September 2003, p. 19

- ^ "A Woman of No Importance", This is Theatre. Retrieved 15 April 2021

- ^ "A Woman of No Importance", Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 15 April 2021; and "Wilde to Aid of Shakespeare Again", The Sun, 25 April 1916, p. 5

- ^ "Criterion Theatre", Truth, 10 January 1897, p. 2

- ^ "Une femme sans importance", "L'Éventail de Lady Windermere", "Un mari idéal and "L'Importance d'être Constant", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 15 April 2021

- ^ Parker, pp. 1849–1875

- ^ "Plays of the month", The Theatre, 1 June 1893, p. 333

- ^ "The London Theatres", The Era, 22 April 1893, p. 9

- ^ "'A Woman of No Importance' at the Haymarket", The Pall Mall Gazette, 20 April 1893, p. 2

- ^ "Haymarket Theatre", The Times, 20 April 1893, p. 5

- ^ Yeats, W. B. "A Woman of No Importance", The Bookman, December 1934, p. 201

- ^ Ellmann, p. 357.

- ^ Raby, p. 154

- ^ "A Woman of No Importance", BBC Genome. Retrieved 15 April 2021

- ^ "A Woman of No Importance (1960)", British Film Institute. Retrieved 15 April 2021

Sources

[edit]- Ellmann, Richard (1988). Oscar Wilde. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-24-112392-8.

- Parker, John, ed. (1939). Who's Who in the Theatre (ninth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 1036973910.

- Raby, Peter (1997). "Wilde's Comedies of Society". In Raby, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Oscar Wilde. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-147987-5.

- Wearing, J. P. (1976). The London Stage, 1890–1899: A Calendar of Plays and Players. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-81-080910-9.

- Wearing, J. P. (1981). The London Stage, 1900–1909: A Calendar of Plays and Players. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. OCLC 1245534136.

- Wilde, Oscar (1964). Rupert Hart-Davis (ed.). De Profundis. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 9780380007011. OCLC 1029021460.

- Wilde, Oscar (1966). Plays. London: Penguin. OCLC 16004478.

External links

[edit] Media related to A Woman of No Importance at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to A Woman of No Importance at Wikimedia Commons The full text of A Woman of No Importance at Wikisource

The full text of A Woman of No Importance at Wikisource