Charles Santley

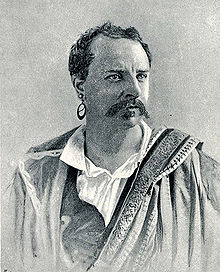

![Photograph of Charles Santley, [ca. 1859–1870]. Carte de Visite Collection, Boston Public Library.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/10/Charles_Santley_-_DPLA_-_7f394a3ebe68ee176453a91ff818b337_%28page_1%29.jpg/220px-Charles_Santley_-_DPLA_-_7f394a3ebe68ee176453a91ff818b337_%28page_1%29.jpg)

Sir Charles Santley (28 February 1834 – 22 September 1922) was an English opera and oratorio singer with a bravura[Note 1] technique who became the most eminent English baritone and male concert singer of the Victorian era. His has been called 'the longest, most distinguished and most versatile vocal career which history records.'[1]

Santley appeared in many major opera and oratorio productions in Great Britain and North America, giving numerous recitals as well. Having made his debut in Italy in 1857 after undertaking vocal studies in that country, he elected to base himself in England for the remainder of his life, apart from occasional trips overseas. One of the highlights of his stage career occurred in 1870 when he led the cast in the first Wagner opera to be performed in London, The Flying Dutchman, at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Santley retired from opera during the 1870s in order to concentrate on the lucrative concert circuit.

Santley also wrote books on vocal technique and two sets of memoirs.

Early training

[edit]

Santley was the elder son of William Santley, a journeyman bookbinder,[2] organist and music teacher of Liverpool in northern England.[3] He had a brother and two sisters, one of whom named Catherine should not be confused with the actor-manager Kate Santley.[4] He was educated at the Liverpool Institute High School, and as a boy sang alto in the choir of a local Unitarian church.[5] His voice began to break before he was fourteen. Following musical lessons from his father (who insisted upon his singing tenor[6]), he passed the examination for admission to the second tenors of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society on his fifteenth birthday, and in the same year took part in the concerts at the opening of the Philharmonic Hall.[5]

It was not until he reached the age of seventeen to eighteen that he rebelled against his father's decree and dropped into the bass clef, and was pronounced to be a bass.[7] Santley was apprenticed to the provision trade. He enlisted, however, as a violinist in the Festival Choral Society and the Società Armonica, and as a chorus member, with his father and sister, he sang in a performance of Haydn's The Creation at the Collegiate Institution, Liverpool, in which Jenny Lind was a soloist. Soon afterwards he was in a hand-picked choir for Handel's Messiah, where the tenor Sims Reeves headed the soloists, at the Eisteddfod at Rhuddlan Castle, and was in the chorus for Elijah and Rossini's Stabat Mater under Julius Benedict at the Liverpool Festival. He heard Pauline Viardot, Luigi Lablache and Mario there. While acting as accompanist to his sister at St Anne's Catholic Church, Edge Hill, Liverpool, he sang 'Et incarnatus est' from Haydn's Second Mass, reading from the same score as Julius Stockhausen, as a trial, and obtained a place as bass soloist, modelling himself upon the style of the Austrian bass Josef Staudigl (1807–1861), and of the German bass Karl Formes (1815–1889) (whom he heard as Sarastro in London).[2][8]

In 1855, Santley went to Italy to study as a singer, with advice from Sims Reeves to visit Lamperti in Milan. However he chose to study under Gaetano Nava, who became his lifelong friend. Nava taught him buffo roles in Rossini's La Cenerentola, L'italiana in Algeri and Il Turco in Italia, and in Mercadante's operas, laying the basis of sound vocal technique as a baritone. He also taught him Italian speech. Santley studied duets from Bellini's Zaira and Rossini's Semiramide and The Siege of Corinth. He was a frequent guest at concerts and conversaziones of the Marani family. At the theatres, he heard Antonio Giuglini, Scheggi, Marini and Enrico Delle Sedie, and saw Ristori in Maria Stuarda, attending La Scala, Milan, and the Carcano Theatre.

He made his stage debut on 1 January 1857 in Pavia as Dr Grenvill in La traviata (later in the same run singing Germont père), and Don Silva in Ernani. Other minor engagements followed, After a thin summer, however, Henry Fothergill Chorley visited and urged his return to England.[2]

Oratorio, 1857–1872

[edit]In 1857 Santley returned to London, and made his first appearance (16 November) for John Hullah in the role of Adam in Haydn's Creation: it is related that he broke down in the duet Graceful Consort owing to nerves, but the audience burst into applause for him and bade him continue.[9] Manuel García, who heard him, offered training which Santley accepted gratefully. There were a few concerts at the Crystal Palace and elsewhere, under Chorley's guidance, and at a Chorley party he met Gertrude Kemble, who became his wife a year later. Through her he was introduced to the salon of Henry Greville, at whose musical parties he joined company with Mario, Giulia Grisi, Italo Gardoni, Ciro Pinsuti and others.[2]

After an audition with Michael Costa, he sang in Mendelssohn's St. Paul in Manchester under Charles Hallé, and in March 1858 he first sang Mendelssohn's Elijah (at Exeter Hall, Liverpool), of which he became a leading interpreter[10] for over 50 years. From the first, he was given firm encouragement by Sims Reeves and Clara Novello, and by Mario and Grisi, with whom he sang on various occasions. At the inauguration of the original Leeds Festival of autumn 1858 he was the star performer (with Willoughby Weiss) in Rossini's Stabat Mater . In the autumn of 1859 he was singing items from St Paul, Judas Maccabaeus and Messiah at the Bradford Festival, shortly before embarking on his initial operatic season.[2]

In 1861 he sang Elijah in his first appearance at the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival.[2][11] In July of the following year, at St James's Hall Piccadilly, he appeared in the Philharmonic Society's 50th Jubilee Concert, singing an item from Hummel's Mathilde of Guise, and With Joy the Impatient Husbandman from Haydn's The Seasons. On that occasion he shared a platform (though in separate performance) with Jenny Lind, the pianist Lucy Anderson (her last public appearance), Thérèse Tietjens, and Alfredo Piatti the cellist, under the direction of William Sterndale Bennett. Bennett had just drilled a new orchestra to a level of high efficiency, creating a sensation before a huge audience.[12] In 1862 Santley appeared at the Handel Festival at the Crystal Palace.[11]

The year 1863 saw his first appearance at the Worcester and Norwich festivals: at Worcester he sang in Schachner's new work Israel's return from Babylon, and at Norwich he introduced Julius Benedict's Richard Coeur de Lion, a great success. In April 1864 he sang in Handel's Messiah, and in a miscellaneous concert, at Stratford-upon-Avon for the Shakespeare centenary festival. At the Hereford Festival he sang the second part of The Creation, an English version of Rossini's Stabat Mater and Benedict's Richard. At the Birmingham festival of 1864 was given Michael Costa's new work Naaman, where (as Elisha) he sang opposite Sims Reeves and the young Adelina Patti (then making her first appearance in oratorio).[13] Santley also appeared there in Messiah and Arthur Sullivan's The Masque at Kenilworth.[2]

The autumn of 1865 witnessed his debut appearance at the Gloucester Festival, where he sang Elijah, the first part of St. Paul, part of Messiah, and Mendelssohn's First Walpurgis Night. In 1866 he was at Worcester Festival, and then at Norwich, where Costa's Naaman was given again, in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and Benedict's new cantata St Cecilia (libretto by Chorley) was introduced. At Hereford in 1867 the main event for Santley was singing with the famous soprano Jenny Lind for the first time, in the oratorio Ruth by Otto Goldschmidt. There, and at Birmingham festival, Willoughby Weiss took most of the sacred bass or baritone roles. Santley sang bass arias from the Messiah, Gounod's Mass, Benedict's St Cecilia and J. F. Barnett's The Ancient Mariner.[2]

Returning to the Birmingham Festival in 1867 he was a soloist in the premiere of the Sacred Cantata The Woman of Samaria by William Sterndale Bennett, conducted by the composer.

At the Handel Festival in June 1868 he sang the Messiah solos, and on the selection day, 'O voi dell'Erebo' from La Resurrezione and 'O ruddier than the cherry' from Acis and Galatea. He also sang 'The Lord is a Man of War' with Signor Foli. At Hereford he sang Dr Wesley's anthem The Wilderness, and under Dr Wesley, Elijah, with Louisa Pyne. In 1869 a Rossini festival took place at the Crystal Palace, with a chorus and orchestra of about 3,000, in which he sang in the Stabat Mater, and appeared in the scene of the 'Blessing of the Banners' from The Siege of Corinth. In mid-May he sang in the first performance in England of Rossini's Petite Messe Solennelle, with the dramatic soprano Thérèse Tietjens, Pietro Mongini and the mezzo-soprano Sofia Scalchi. It was also performed that year at the Worcester and Norwich festivals. At Worcester, Reeves, Santley, Trebelli and Tietjens gave the first performance of Sullivan's The Prodigal Son, under the composer's baton. At Norwich there was also Hugo Pierson's oratorio Hezekiah.[2]

At the close of the 1868–69 season of the Philharmonic Society of London Santley, Tietjens and Nilsson took part in the final supernumerary concert, held at St James's Hall for the first time before the Society moved there permanently in the next season. These three singers were among the original ten recipients to be awarded the Society's gold medal at its first presentation in 1871.[14]

In early 1870, as his departure from the theatre was approaching, Santley sang at concerts in London and at Exeter Hall. Then, under the management of George Wood, he made a six-week concert tour of the provinces. The touring company included Clarice Sinico, the violinist August Wilhelmj and the pianist Arabella Goddard (later joined by Ernst Pauer). Santley's concert singing reached a high point of acclaim during his subsequent United States and Canadian tour of 1871–72. In such songs as "To Anthea", "Simon the Cellarer" and the "Maid of Athens", he was viewed as being unapproachable, and his oratorio singing was praised for perpetuating the finest traditions of the art form.[11] In 1872, he took part in a joint recital with Pauline Rita at St James's Hall, London.[15]

Operatic career 1857–1876

[edit]The early years

[edit]In the first years after his return to England, Santley used often to sing buffo duets (for example 'Che l'antipatica vostra figura' from Ricci's Chiara di Rosemberg) with Giorgio Ronconi and Giovanni Belletti, at parties held by the influential critic H. F. Chorley. In 1859 he made his debut at Covent Garden as Hoel in Meyerbeer's opera Dinorah.[11][16] In the same season he sang in the English Il trovatore (Di Luna), The Rose of Castille, Satanella, La sonnambula, and as Rhineberg in Wallace's Lurline, with William Harrison and Louisa Pyne. Wallace transcribed the latter role (originally for bass) to suit his higher register, and composed the character's part in the final act expressly for him.[17] Dinorah also received a royal command performance before Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was also able to fit in performances of Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride in Manchester, with Sims Reeves and Catherine Hayes, for Charles Hallé. These were twice repeated at the residence of Lord Ward in Park Lane, London.[2]

Santley appeared in English opera for Mapleson at Her Majesty's Theatre in the 1860–61 season. Mapleson mounted a new opera, George Alexander Macfarren's Robin Hood, featuring a cast led by Sims Reeves and stage-debutante Helen Lemmens-Sherrington, under the direction of Charles Hallé. In the same season Santley sang (for Pyne and Harrison) Fra Diavolo, La Reine Topaze, The Bohemian Girl (with Mme Parepa), Il trovatore and Wallace's The Amber Witch, which later transferred to Drury Lane.[18] He was announced to sing in Verdi's Macbeth with Giulia Grisi in 1861, but the promotion collapsed.[2]

For the season of 1861–62, Santley returned to Covent Garden, opening in Howard Glover's Ruy Blas (as Don Sallust, Harrison as Ruy Blas), then in a re-cast version of Robin Hood, and finally in Balfe's The Puritan's Daughter. He also created the role of 'Danny Man' in Julius Benedict's The Lily of Killarney, which was performed nightly for five or six weeks. Worn out by this busy season, Santley decided to turn his attention to Italian opera, and, armed with a letter from Michael Costa, paid a visit to Rossini in Paris. This meeting proved disappointing; but he made an Italian début at Covent Garden in 1862 when he sang the role of di Luna in Il trovatore for three nights at Covent Garden, 'in place of Graziani, to oblige Mr. Gye':[19] that was with the English soprano Fanny Gordosa, Constance Nantier-Didiée, the Italian dramatic tenor Enrico Tamberlik and the Franco-Italian bass-baritone Joseph Tagliafico. Santley's performances were received rapturously by the Covent Garden audience.[2]

Mapleson's Italian Opera

[edit]

Mapleson won Santley back for his own Italian opera company, and in the 1862–63 season at Majesty's, he performed in Il trovatore (as Di Luna), The Marriage of Figaro (as Almaviva) and Les Huguenots (as de Nevers). He returned to Covent Garden for the English Opera, however, appearing in the Lily of Killarney, Dinorah, and Balfe's The Armourer of Nantes. In defence of his decision to move to Italian opera, Santley notes that since 1859-60 he had been singing about 110 opera performances per season, in addition to fulfilling concurrent concert engagements.[2]

With Mapleson's Italian Opera he joined some of the 19th century's most celebrated singers, including Thérèse Tietjens, Marietta Alboni, Antonio Giuglini and Zelia Trebelli. Once the 1862–63 season was over, Santley paid a visit to Paris and saw Mme Carvalho perform in Gounod's Faust, which Mapleson had obtained for the 1863 season in London. In the new season (begun with Il trovatore), Carvalho and Santley appeared together in the premiere of Schira's Niccolo de' Lapi, Santley creating the title-role. He also played the elder Germont in La traviata.[2]

The first performance of Faust in England followed. It was given in a problematic English translation by Henry Fothergill Chorley, which nevertheless remained the standard translation until well into the 20th century. Santley appeared as Valentine. The other cast members were Tietjens (as Marguerite), Trebelli (Siebel), Antonio Giuglini (Faust) and Edouard Gassier (Mephisto). In July 1863 the company performed Weber's Oberon with Reeves, Tietjens, Alboni and Alessandro Bettini. Santley appeared as Scherasmin. In the autumn, after the Worcester and Norwich festivals, Santley joined the Mapleson company's annual tour, beginning in Dublin. Sims Reeves had joined the company to perform the roles of Edgardo, Huon and Faust (with Tietjens and Trebelli as his partners).[2]

After hearing Santley's Valentine, Gounod composed the aria Even bravest heart expressly for him to an original English text by Chorley (now, ironically, better known in French translation as Avant de quitter or in Italian as Dio possente) and this was introduced in London in January 1864 at the opening of the spring session. Also appearing in this production were Reeves, Lemmens-Sherrington and Salvatore Marchesi (the latter as Mephisto). Late in the run, however, Santley took on the role of Mephisto, in an 'abominable red costume'. Faust was later produced with Tietjens, Gardoni, Trebelli, and Signor Junca, with Santley resuming his place. In the same season he appeared in the English premiere of Nicolai's Die Lustigen Weiber von Windsor and in Gounod's Mireille (with Giuglini and Tietjens). He appeared, too, as Plunkett in Martha, as the Duke in Lucrezia Borgia, and as the Minister in Fidelio.[2]

The company in transition

[edit]

After the festival season, Santley toured in Mapleson's company during the autumn (with Italo Gardoni as lead tenor), appearing in Faust, Oberon and Mireille, In November 1864 he set off for Barcelona, where he was booked for a three-month season at the Liceu. His Di Luna was warmly received, and he followed with his first Rigoletto, and La traviata. He also played Enrico in Lucia, Obertal in Le Prophète, and Renato in Un ballo in maschera. He arrived back in Britain to join Mapleson's spring tour at Dublin, on the same day stepping in at Tietjens's insistence to save a failing production of Lucrezia Borgia. During this tour he also performed Carlo Quinto in Ernani for the first time and sang at the Theatre Royal at Liverpool, the fulfilment of a childhood ambition.[2]

In the spring of 1865, Giuglini left the company, and the Croatian diva Ilma de Murska[20] joined it, appearing in Lucia di Lammermoor. Santley took on three new roles: Papageno in Mozart's Magic Flute, Creonte in Cherubini's Médée and Pizarro in Beethoven's Fidelio (opposite Tietjens). In September there was a short touring season, in which he played Don Giovanni (with Mario) for the first time, at Manchester. He also sang Caspar in Der Freischütz in London in October. Santley then went on to appear in a season at La Scala, Milan, where Il trovatore was staged for his debut there as de Luna (he alone of all the cast was not hooted by the audience[21]), as well as Nicolai's Il Templario (in which he sang the role of Brian the Templar). Returning to London in March 1866, Santley appeared in the spring season with Tietjens, Gardoni and Gassier in Iphigénie en Tauride. He also sang in Dinorah (with de Murska and Gardoni) and Ernani (with Tietjens, Tasca and Gassier). During the autumn, he performed as Leporello in Don Giovanni at Her Majesty's.[2]

The year 1867 brought the engagement of Sweden's Christine Nilsson, and Santley appeared with her in La traviata and I Lombardi. La forza del destino was also given, along with Don Giovanni, Dinorah, Fidelio, Oberon, Medea, Der Freischütz and Les Huguenots. After the autumn tour with Alessandro Bettini in Les Huguenots, the November session opened with Faust, followed by La traviata and Martha, and Linda di Chamounix, in which Santley first sang the part of Antonio. Don Giovanni, with Clara Louise Kellogg as Zerlina and Santley as Leporello, proved to be the final operatic performance of that season: Santley had been due to play Pizarro, when the news came to him, while he was appearing in concert in Brighton, that Her Majesty's Theatre had been burnt to the ground. Santley had sung the last notes ever to be heard in that theatre.[2]

After the fire

[edit]The company presented a fresh season, commencing in March 1868 at Drury Lane. In it, Santley sang Fernando in La Gazza Ladra with Kellogg, Trebelli, Bettini and Foli, and the title role in Rigoletto with Kellogg and the prominent tenor Gaetano Fraschini. Also produced at Drury Lane that season were Les Huguenots, Le nozze di Figaro, La Figlia del Reggimento and Faust (with Nilsson as Marguerite). At Nilsson's benefit concert, Santley played the final scene of I Due Foscari, and his Doge was compared favourably to Ronconi's.[2]

In July Santley appeared in Le Nozze at the Crystal Palace. The London autumn season was held at Covent Garden, with Santley's old hero Karl Formes joining the tour cast. The American soprano Minnie Hauk also appeared (in La Sonnambula). During the ensuing tour, Santley sang Tom Tug in Charles Dibdin's The Waterman for the first time, at Leeds. The next season, he sang it twice more in Leeds, and once each in Sheffield and Bradford. The airs from The Waterman 'The jolly young waterman' and 'Then farewell, my trim-built wherry' were sung by Santley to acclaim.[2]

Her Majesty's remained closed, and in 1869 Mapleson was drawn into a merger with the Royal Italian Opera. With the merged company, Santley performed in Rigoletto with Vanzini,[22] Scalchi, Mongini and Foli, in Norma and Fidelio, in Linda di Chamounix with di Murska and in Il trovatore. La Gazza Ladra was also staged with Santley appearing opposite Trebelli, Bettini and Patti. Santley led the cast, with Nilsson as his Ophelia, in the London premiere of Hamlet by Ambroise Thomas. He enjoyed the role, which was sung in Italian, apart from the 'Brindisi'. He also played Hoel in Dinorah opposite Patti, and although a planned partnership with her in L'Etoile du Nord did not occur, they did perform Rigoletto together for Patti's benefit. Santley's Hamlet was repeated in the autumn, with de Murska replacing Nilsson, and with Karl Formes as the ghost.[2]

Early in 1870 the company made an operatic tour of Scotland, during which Santley sang Don Giovanni. At Drury Lane, in the following Italian season managed by George Wood, Santley sang The Dutchman in The Flying Dutchman (in Italian, as L'Ollandese Dannato), opposite di Murska, and with Signor Foli as Daland. This was the first presentation of a Wagner opera in London. It took place in July 1870. But several other promised productions either did not occur (Macbeth, Cherubini's Les Deux Journees, Rossini's Tancredi) or the baritone role in them was given to another artist. (Lothario in Thomas' Mignon, for example, was assigned not to Santley but to the French baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure).[2]

Attempt to found an English lyric theatre

[edit]Rather than accept another season with the joint company, Santley decided to establish a new English Opera enterprise at the Gaiety Theatre, working with the theatre's music director and conductor, Meyer Lutz. In autumn 1870 he launched a successful nine-week run at the Gaiety with Hérold's Zampa. He refused to sing Don Giovanni but he did stage Fra Diavolo (with himself in title role), and, in the lead-up to Christmas, The Waterman. Performances of Fra Diavolo continued through February 1871, while Lortzing's Czar und Zimmerman (as Peter the Shipwright) was staged for Easter. This production proved a success but Santley could not persuade the Gaiety's manager, John Hollingshead, to produce Auber's Le Cheval de bronze as a follow-up. Feeling that his long-cherished project of an English lyric theatre could never be accomplished, he decided to turn his back on the stage altogether. Instead, in 1872–1873, he set out on a concert tour of in the United States and Canada.[2]

With Carl Rosa's company

[edit]

The concert tour itself was not a financial success. Santley therefore entered into an agreement with Carl Rosa to join his Italian season in New York City in March 1872; but he joined them first for the English season to play Zampa and Fra Diavolo, at Baltimore, Philadelphia, Newark and elsewhere. He played Valentin in Faust at Philadelphia. In the Italian season, from mid-March to the end of April, he was with Mme Parepa-Rosa, Adelaide Phillips and the tenor Theodore Wachtel (1823–1893), and with Karl Formes, who sang Marcel in Les Huguenots with Santley (Saint-Bris), at the Academy of Music in New York under Adolph Neuendorff.[23] Santley was also particularly proud to have sung once in that season with his friend and idol, Giorgio Ronconi, who was Leporello to Santley's Don Giovanni. The company also played Il trovatore, Rigoletto, Lucrezia Borgia, Martha and Guglielmo Tell. The houses and receipts were enormous, and they sailed to England well pleased in early May 1872.[2]

In 1873 Carl Rosa invited Santley to appear as Telramund in a planned English Lohengrin at Drury Lane. Santley accepted, but the project failed with the untimely death of Mme Parepa-Rosa. (Lohengrin was not heard in London until 1875).[24] Santley's wish to play Wolfram in Tannhäuser also remained unrealised. He disliked the prominence of the Wagnerian orchestra and regretted the innovation which saw orchestral players being relegated to a pit beneath the opera stage.[2]

However, in 1875 Carl Rosa tempted him back to the stage for a season at the Princess's Theatre, London, in which he played in Le nozze di Figaro, Il trovatore, The Siege of Rochelle (as Michel), Cherubini's The Water Carrier (Mikelì) and The Porter of Havre (Martin). In Figaro he was cast as Almaviva, but was transferred to the role of Figaro, singing with Sig. Campobello[25] (Almaviva), Aynsley Cook (Bartolo), Charles Lyall (Basilio), Ostava Torriani (Contessa), Rose Hersee (Susanna), Josephine York (Cherubino) and Mrs Aynsley Cook (Marcellina). This received a special performance for the Prince and Princess of Wales. There was a provincial tour in the autumn.[2]

In autumn 1876 at the Lyceum Theatre, again with Carl Rosa, Santley revived his Flying Dutchman, this time in English, with Ostava Torriani as Senta. Between the London season and the provincial tour which followed they performed it 50 times. Among the cities visited were Edinburgh (four performances) and Glasgow (two performances).[26] In the same season they undertook a work new to him, Nicolo's Joconde, and he played Zampa and The Porter of Havre again. The final work was a new opera with a role (Claude Melnotte) written especially for him, the Pauline of F. H. Cowen: the work was not successful. The tour took them to Dublin, Sheffield, Hanley and Birmingham. That, apart from two appearances as Sir Harry in The School for Scandal at Drury Lane benefits, and his eventual farewell appearance at Covent Garden in 1911,[27] was the end of his stage career.[2]

Later years

[edit]

Santley gave recitals at the Monday Popular Concerts, and appeared with the Joachim String Quartet and Mme Clara Schumann.[28] He settled down to concert and oratorio work in England.

Santley, to whom European travel had been a holiday routine for many years, toured in Australia and New Zealand in 1889–1890, to the United States and Canada in 1891 and South Africa in 1893 and again in 1903. He sang last at the Birmingham festival in 1891 after an unbroken series of thirty years of appearances there. George Bernard Shaw, describing Santley as the hero of the 1894 Handel Festival, remarked especially on his Honour and Arms and Nasce al Bosco. 'Santley's singing of the division of Selection Day was, humanly speaking, perfect. It tested the middle of his voice from C to C exhaustively; and that octave came out of the test hall-marked; there was not a scrape on its fine surface, not a break or a weak link in the chain anywhere; while the vocal touch was impeccably light and steady, and the florid execution accurate as clockwork.' In these two arias his entire compass from low G to top E flat, and in Nasce al Bosco the top E natural and F, were exhibited 'in such a way as made it impossible for him to conceal any blemish, if there had been one.'[29]

In January 1894 he was with Clara Butt, Edward Lloyd, Antoinette Sterling and other singers at the first of the Chappell's Ballad Concerts, when they were transferred from St James's Hall to Queen's Hall.[30] From 1894 Santley devoted his time increasingly to teaching: between 1903 and 1907 he trained the Australian baritone Peter Dawson, taking him meticulously through Messiah, The Creation and Elijah.[31] Indeed, in 1904 he brought Dawson in on a tour of the West Country, beginning at Plymouth, led by Emma Albani, with William Green (tenor), Giulia Ravogli, Johannes Wolf, Adela Verne and Theodore Flint.[32]

In January 1907 he sang Elijah at Manchester Town Hall, having sung Messiah and Elijah every year there since 1858.[33] He celebrated the jubilee of his singing career in the company of many of his musician friends at a grand benefit concert held at the Royal Albert Hall on 1 May 1907. He was knighted (the first singer to receive this honour) in December of that year, after singing at Bristol, and sang Elijah at Hanley two days later.[33] Over the next months he gave short recitals at Liverpool and sang Elijah at Edinburgh.[33] He made his Covent Garden farewell in 1911 as Tom Tug in Charles Dibdin's The Waterman.[27] In 1915, at the request of London's Lady Mayoress, he sang at the Mansion House concert for Belgian refugees, when the accurate intonation, fine quality and vigour of his voice were still apparent.

Vocal character

[edit]In addition to a 'haunting' beauty of timbre,[34] Santley's technique and musicianship made him a master in the singing of Handel or Mozart, where a fresh and accurate management of rhythm and roulade created an effect of spontaneity, vigour and ideal phrasing.[35] His ensemble singing was also noted, for example, as Figaro[36] and in Fidelio.[37] Henry J. Wood observed that his compass ranged from the bass E-flat to the baritone top G, and was exceptionally even throughout. 'All his low F's told – even to the remotest corners of the largest concert-hall while his top F's were as a silver trumpet.'[38] His clarity and freedom from strain enabled him to continue singing with remarkable freshness throughout a career lasting more than 60 years, perhaps partly because he had not over-taxed his voice by remaining for too long on the operatic stage.[39]

George Bernard Shaw, who first saw him on stage as Di Luna in Il trovatore, considered that Santley's dramatic powers were 'blunt, unpractised, and prone to fall back on a good-humoured nonchalance in his relations with the audience, which was highly popular, but which destroyed all dramatic illusion. He was always Santley, the good fellow with no nonsense about him, and a splendid singer.... The nonchalance was really diffidence....'[40] He played Valentin, in Faust, 'in an unfinished, hail-fellow-well-met way.' Later on, as Vanderdecken, etc., 'his dramatic grip was much surer; and at the present moment [1892], on the verge of his sixtieth year, he is a more thorough artist than ever.'[41]

Personal life

[edit]Santley married twice, first (in 1858) to Gertrude Kemble (granddaughter of Charles Kemble), who before her marriage had a professional career as a soprano singer. Their daughter Edith also became a concert singer. Gertrude died in 1882. The couple had five children.[42]

Santley's second marriage, on 7 January 1884,[43] was to Elizabeth Mary Rose-Innes (Isabel María Rose-Innes Vives), eldest daughter of George (Jorge) Rose-Innes, a Valparaíso merchant and banker whose father was British. They had one son.[44]

Santley converted to Roman Catholicism in 1880, and in 1887 Pope Leo XIII created him a Knight Commander of St Gregory the Great.

Recordings

[edit]Charles Santley made a few recordings, mostly of ballads. His earlier series was made for the Gramophone Company (His Master's Voice) in 1903.[45] Although the voice lacks much of its former brilliant resonance due to age it remains firm and steady. His most famous record preserves his remarkably vivid and lively rendering of 'Non piu andrai' (Figaro), employing a portamento (notably on the word 'narcisetto', usually broken by modern interpreters) that is fit to satisfy Garcia himself.[46] He did not commit any souvenirs of his Handel performances to disc. His 1903 discs are:

- 2-2862 Simon the Cellarer (Hatton) (10")

- 2-2863 The vicar of Bray (10")

- 052000 Ehi capitano/Non piu andrai (Figaro – Mozart) (12")[47]

- 2-2864 To Anthea (Hatton) (10")

- 02015 Thou'rt passing hence, my brother (Sullivan) (12")

Several years later he cut a group of ballad titles for the Columbia label. Hatton's 'To Anthea' and 'Simon the Cellarer' are characteristic of Santley's earlier ballad repertoire, and are repeated in the Columbia series, which also includes Ethelbert Nevin's 'My Rosary', C.V. Stanford's 'Father O'Flynn,' Sullivan's 'Thou'rt passing hence, my brother,' and other titles.[48]

Books

[edit]Santley's publications include the following:

- Method of Instruction for a Baritone Voice, a translation of "Metodo pratico di vocalizzazione, per le voci de basso e baritono" by G. Nava (London, c 1872)

- Student and Singer, Reminiscences of Charles Santley (Macmillan, London 1893)

- The Singing Master (1900)

- The Art of Singing and Vocal Declamation (1908)

- Reminiscences of my Life (Isaac Pitman, London 1909)

Of the volumes of reminiscences, Student and Singer deals with his career up to circa 1870, and Reminiscences of My Life includes material for the later period.

Compositions

[edit]- Mass in A flat

- Ave Maria, Berceuse for Orchestra

Santley also composed a number of songs under the pseudonym of Ralph Betterton.[49]

Notes

[edit]- ^ From the Italian verb bravare, to show off. A florid, ostentatious style or a passage of music requiring technical skill

References

[edit]- ^ Arthur Eaglefield-Hull, A Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians (Dent, London 1924), 435.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab C. Santley, Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley 3rd Edition (Edward Arnold, London 1892), p.6.

- ^ Eaglefield-Hull 1924: Rosenthal & Warrack, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera.

- ^ 1851 and subsequent Census returns for 20 Hardwick Street, West Derby, Liverpool (National Archives HO 107.2192).

- ^ a b John Warrack, "Santley, Sir Charles (1834–1922)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 28 April 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art if Singing' (1908), p. 16.

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), p. 16.

- ^ Rosenthal & Warrack 1974.

- ^ H.J. Wood, My Life of Music (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1946 edition), p. 17.

- ^ William Ludwig's conception of Elijah was considered nobler by some, see Henry Wood, My Life of Music, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 194.

- ^ R. Elkin, Royal Philharmonic (Ryder, London 1946), p. 62.

- ^ S. Reeves, The Life of Sims Reeves, Written by Himself (Simpkin, Marshall, London 1888), p. 217-218.

- ^ R. Elkin, Royal Philharmonic (Rider, London 1946), 65-71.

- ^ Daily News, 22 May 1872, p. 3

- ^ C. Santley, 'The Art of Singing and Vocal Declamation' (Macmillan and Co., London 1908), pp. 15-17.

- ^ Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), pp. 17-18.

- ^ Santley 1892, 171–72: J. H. Mapleson, The Mapleson Memoirs (Belford, Clarke & Co, Chicago & New York 1888), I, 28.

- ^ Santley, 'The Art of Singing' (1908), p. 18.

- ^ 'di' Murska in Rosethal and Warrack, and in Santley 1892, 'de' Murska in Mapleson 1888.

- ^ Illustrated London News, 3 March 1866, p. 215.

- ^ Mrs Van Zandt, mother of the Mlle. van Zandt who sang at the Opéra-Comique.

- ^ 'Adolph Neuendorff dead', The New York Times 5 December 1897

- ^ Rosenthal and Warrack 1974.

- ^ Signor Campobello was the stage name of Henry McLean Martin, baritone. According to Groves' Dictionary 1890 edition, in 1874 he married the soprano Clarice Sinico, née Marini, afterwards known as Mme Sinico-Campobello.

- ^ Design, Site Buddha Web. "Charles Santley – Opera Scotland".

- ^ a b Eaglefield-Hull 1924, 435.

- ^ Eaglefield-Hull 1924.

- ^ G. B. Shaw, Music in London 1890-94 (Constable, London 1932), III, 254-257.

- ^ R. Elkin, Queen's Hall 1893-1944 (Rider, London 1944), 91.

- ^ P. Dawson, Fifty Years of Song (Hutchinson, London 1951), 17-20.

- ^ Dawson 1951, 25-26.

- ^ a b c Santley 1909

- ^ Herman Klein, Thirty Years of Music in London 1870-1900 (Century Co., New York 1903), 466.

- ^ Klein 1903, p. 466: M. Scott, The Record of Singing I (Duckworth, London 1977), p. 52-53, quoting Hanslick and John McCormack.

- ^ Klein 1903, 49, & n.

- ^ M.J.C. Hodgart and R Bauerle, Joyce's Grand Operoar: Opera in Finnegans Wake (Illinois University Press 1997, ISBN 0-252-06557-3), p. 25.

- ^ H. J. Wood, My Life of Music (Gollancz, London 1946 (Cheap edition)), p. 91.

- ^ G. Davidson, Opera Biographies (Werner Laurie, London 1955), 267.

- ^ G. B. Shaw, Music in London, 1890-94 (Constable, London 1932), II, 195.

- ^ Shaw 1932, II, 196.

- ^ "Kemble Genealogy Page". Archived from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- ^ "Marriage: Santley–Rose-Innes". The Tablet. 63 (2283). London: 92. 19 January 1884.

- ^

- White, Maude Valerie (1914). Friends and memories. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 75, 236.

- Coo Lyon, José Luis (1971). "Familias extranjeras en Valparaíso en el siglo XIX". Revista de estudios históricos (in Spanish) (17). Instituto Chileno de Investigaciones Genealógicas: 33.

- ^ Bennett 1955,: Bennett 1967.

- ^ Reproduced and discussed in M. Scott, The Record of Singing, Vol. I (Duckworth, London 1977).

- ^ This title in Bennett 1967.

- ^ Scott 1977, 52-53.

- ^ "AIM25 collection description".

Bibliography

[edit]- J.R. Bennett, Voices of the Past – Catalogue of Vocal recordings from the English Catalogues of the Gramophone Company, etc. (c1955).

- J.R. Bennett, Voices of the Past – Vol 2. A Catalogue of Vocal recordings from the Italian Catalogues of The Gramophone Company, etc. (Oakwood Press (1957), 1967).

- G. Davidson, Opera Biographies (Werner Laurie, London 1955), 264–267.

- J.H. Mapleson, The Mapleson Memoirs (Chicago & New York 1888).

- S.Reeves, Sims Reeves, His Life and Recollections Written by Himself (Simpkin Marshall & Co, London 1888).

- H. Rosenthal and J. Warrack, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera (Corrected Edition, Oxford 1974).

- M. Scott, The Record of Singing to 1914 (Duckworth 1977).

- G.B. Shaw, 1932, Music in London 1890-94 by Bernard Shaw, 3 Vols (Constable & Co, London)

- Herbert Thompson, Herbert. "Sir Charles Santley 1834-1922", The Musical Times, Vol. 63, No. 957 (1 November 1922), pp. 784–92