George Town, Penang

George Town

Bandaraya Pulau Pinang | |

|---|---|

| City of Penang Island | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Mandarin |

|

| • Hokkien | Pho-té / Kiâu-tī-tshī (Tâi-lô) |

| • Tamil | ஜார்ஜ் டவுன் Jārj Iḍavuṉ (Transliteration) |

| • Thai | จอร์จทาวน์ Chogethao (RTGS) |

Skyline of the city centre The two Penang bridges | |

| Etymology: George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland | |

| Nickname: Pearl of the Orient[1] | |

| Motto: | |

| |

| Coordinates: 05°24′52″N 100°19′45″E / 5.41444°N 100.32917°E | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Districts | Northeast and Southwest |

| Mukims[3] | City centre and 36 subdistricts |

| Founded[4] | 11 August 1786 |

| Municipality[5] | c. 1857 |

| Incorporated (city)[6] | 1 January 1957 |

| Expansion[7] | 31 March 2015 |

| Founded by | Francis Light |

| Government | |

| • Type | City council |

| • Body | Penang Island City Council |

| • Mayor[8] | Rajendran P. Anthony |

| • City Secretary[9] | Cheong Chee Hong |

| Area | |

| • City[10] | 306 km2 (118 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,759 km2 (1,451 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[11] | |

| • City[10] | 794,313 |

| • Rank |

|

| • Density | 2,596/km2 (6,720/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,844,214 (2nd) |

| • Metro density | 760/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Georgetowner[12] |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | Not observed |

| Postal code |

|

| Area code(s) | 4-2, 4-6, 4-8 |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 1223 |

| Inscription | 2008 (32nd Session) |

George Town is the capital of the Malaysian state of Penang. It is the core city of the George Town Conurbation, Malaysia's second largest metropolitan area with a population of 2.84 million and the second highest contributor to the country's GDP. The city proper spans an area of 306 km2 (118 sq mi) encompassing Penang Island and surrounding islets, and had a population of 794,313 as of 2020[update].

Initially established as an entrepôt by Francis Light in 1786, George Town serves as the commercial centre for northern Malaysia. According to Euromonitor International and the Economist Intelligence Unit, it has the highest potential for revenue growth among all Malaysian cities and contributed nearly 8 per cent of the country's personal disposable income in 2015, second only to the national capital, Kuala Lumpur. Its technological sector, anchored by hundreds of multinational companies, has made George Town the top exporter in the country. The Penang International Airport links George Town to several regional cities, while a ferry service and two road bridges connect the city to the rest of Peninsular Malaysia. Swettenham Pier is the busiest cruise terminal in the country.

George Town was the first British settlement in Southeast Asia, and its proximity to maritime routes along the Strait of Malacca attracted an influx of immigrants from various parts of Asia. Following rapid growth in its early years, it became the capital of the Straits Settlements in 1826, only to lose its administrative status to Singapore in 1832. The Straits Settlements became a British crown colony in 1867. Shortly before Malaya attained independence from Britain in 1957, George Town was declared a city by Queen Elizabeth II, making it the first city in the country's history. In 1974, George Town was merged with the rest of the island, throwing its city status into doubt until 2015, when its jurisdiction was reinstated and expanded to cover the entire island and adjacent islets.

The city is described by UNESCO as having a "unique architectural and cultural townscape" that is shaped by centuries of intermingling between various cultures and religions.[13] It has also gained a reputation as Malaysia's gastronomical capital for its distinct culinary scene. The preservation of these cultures contributed to the designation of the city centre of George Town as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2008.

Etymology

[edit]George Town was named in honour of King George III, the ruler of Great Britain and Ireland between 1760 and 1820.[14][15] Prior to the arrival of the British, the geographical area had been known as Tanjung Penaga, due to the abundance of penaga laut trees (Calophyllum inophyllum) found at the cape (tanjung) of the city.[16]

The city is often mistakenly spelled as "Georgetown", which was never the city's official name. This misspelling may be due to confusion with other places worldwide that share the same name.[17] In common parlance, the city of George Town is also called "Penang", which is the name of the larger state.[18][19]

History

[edit]

British East India Company 1786–1858

British Raj 1858–1867

Straits Settlements 1826–1941; 1945–1946

Empire of Japan 1941–1945

Malayan Union 1946–1948

Federation of Malaya 1948–1963

Malaysia 1963–present

Establishment

[edit]

In 1771, Francis Light, a former Royal Navy captain, was instructed by the British East India Company (EIC) to establish trade relations in the Malay Peninsula. He arrived in Kedah, a Siamese vassal state facing threats from the Bugis of Selangor.[4] Kedah's ruler Sultan Muhammad Jiwa Zainal Adilin II offered Light Penang Island in exchange for British military protection. Light noted the strategic potential of the island as a "convenient magazine for trade" that could enable the British to check Dutch and French territorial ambitions in Southeast Asia, and tried unsuccessfully to persuade his superiors to accept the Sultan's offer.[4][20]

Light was finally authorised to negotiate the British acquisition of Penang Island in 1786.[4] After the cession was finalised with Muhammad Jiwa's successor Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah, Light and his entourage landed on the island on 17 July that year.[21] They took formal possession of the island "in the name of King George III of England" on 11 August.[4][22][23] Penang Island was renamed Prince of Wales Island after the heir to the British throne.[24][25][26] George Town was the first British colonial possession in Southeast Asia and marked the beginning of the gradual British colonisation in Malaya.[26][27]

When Light first landed on the cape, it was densely covered in jungle.[28] After the area was cleared, Light oversaw the construction of Fort Cornwallis, the first structure in the newly established settlement.[4][21] The first roads of George Town – Light, Beach, Chulia and Pitt streets – were created in a grid-like configuration.[28][29] This urban planning method facilitated the easy division, transaction and assessment of land, as well as efficient military deployment. The grid pattern was also replicated in Singapore following the acquisition of the island by Stamford Raffles in 1819.[28]

British rule

[edit]

As Light intended, George Town grew rapidly as a free port and a conduit for spice trade, taking maritime commerce from Dutch posts in the region.[31][32][33] The spice trade allowed the EIC to cover the administrative costs of Penang.[34] The threat of French invasion in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars forced the British to enlarge and reinforce Fort Cornwallis as the garrison for the settlement.[21]

Local governance committees were formed from 1796 to resolve specific matters of administration.[5] However, there were no unified legal systems in place to maintain order in the settlement. Light, who believed that feudal laws instituted by the newly-immigrated settlers were incompatible with British law, initially implemented a system in 1792 whereby matters of justice were partially delegated to local leaders.[35] This decision was ratified by Lieutenant-Governor George Leith in 1800. However, further legal disputes meant that under the directives of the Bengal Presidency, this system was replaced by a set of regulations in 1805, drafted by Leith and revised by John Dickens, the presidency's appointed judge and magistrate for Penang.[36]

In 1807, a Charter of Justice was granted which mandated the establishment of a "Court of Judicature" composed of the Governor, a recorder and three councillors.[37] The high court was inaugurated at Fort Cornwallis in the following year, with Edmond Stanley as recorder.[38] With the establishment of the court, George Town became the first settlement in British Malaya to possess a modern judicial system.[39]

In 1826, George Town was made the capital of the Straits Settlements, which also comprised Singapore and Malacca. In 1832, the administrative centre was relocated to Singapore, as it surpassed George Town in commercial and strategic prominence.[40][41] Despite its secondary importance to Singapore, George Town continued to play a crucial role as a British entrepôt. Following the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and a tin mining boom in the Malay Peninsula, the Port of Penang became a leading exporter of tin.[21][42] By the end of the 19th century, George Town emerged as the foremost financial centre of British Malaya, as mercantile firms and international banks were established.[21][23][42]

Throughout the century, George Town's population grew rapidly in tandem with economic prosperity. Between 1797 and 1830, an influx of immigrants from all over Asia quadrupled its population.[20][37] A cosmopolitan population emerged, comprising Chinese, Malay, Indian, Peranakan, Siamese and migrants of mixed European-Asian lineage referred to as "Eurasians". The population growth also created social problems, such as inadequate health facilities and rampant crime, with the latter culminating in rioting in 1867.[43][44][45]

George Town came under direct British rule when the Straits Settlements became a British crown colony in 1867.[41][46] Law enforcement and immigration control were gradually strengthened to suppress organised crime.[47][48] More investments were also made on the settlement's health care and public transportation.[20][43][49]

Advances in education and living standards gave rise to a non-European gentry and middle class, which in turn fostered nascent intellectual activities and political movements.[47][50] George Town, according to historian Mary Turnbull, emerged as "a Mecca for Asian intellectuals", who perceived it to be more intellectually receptive than Singapore.[20][47][50] The settlement was a centre for reformist newspapers, and attracted political and intellectual figures such as Rudyard Kipling, W. Somerset Maugham and Sun Yat-sen.[21][47][51] However, political turmoil in Qing China and the influx of Chinese migrants posed security concerns among the British authorities. Sun chose George Town as the headquarters for revolutionary activities by the Tongmenghui in Southeast Asia that eventually launched the Wuchang Uprising, a precursor to the Xinhai Revolution that ushered in the beginning of Republican China.[51][52]

World wars

[edit]

George Town emerged from World War I relatively unscathed, except for the Battle of Penang where the Imperial German Navy cruiser SMS Emden sank two Allied warships off the settlement.[53][54] World War II, on the other hand, caused unprecedented social and political turmoil in George Town.[54]

In mid-December 1941, the settlement was subjected to severe Japanese aerial bombardment, forcing inhabitants to flee George Town and take refuge in the jungles.[54] While Penang Island had been designated a fortress before the outbreak of fighting, the British high command led by Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival decided to abandon the island and secretly evacuate George Town's European population, leaving the settlement's Asian residents undefended against the Japanese advance.[54][55] According to historian Raymond Callahan, "the moral collapse of British rule in Southeast Asia came not at Singapore, but at Penang".[56][57]

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) seized George Town on 19 December without encountering any resistance.[54] During Japanese occupation, George Town was only lightly garrisoned by the IJA, while the Imperial Japanese Navy converted Swettenham Pier into a major submarine base for the Axis powers.[54][58][59] Japanese military police imposed order by massacring Chinese civilians under the Sook Ching policy; the victims were buried in mass graves all over the island, such as at Rifle Range, Bukit Dumbar and Batu Ferringhi.[54] Poverty and wanton Japanese brutality towards the local population also forced women into sexual slavery.[54]

Between 1944 and 1945, Allied bombers based in India targeted naval and administrative buildings in George Town, damaging and destroying several colonial buildings in the process.[21][54] The Penang Strait was mined to constrict Japanese shipping.[60] Following Japan's surrender, on 3 September 1945, British Royal Marines launched Operation Jurist to retake George Town, making it the first settlement in British Malaya to be liberated from the Japanese.[54]

Post-war

[edit]

After a period of military administration, the British dissolved the Straits Settlements in 1946 and merged the Crown Colony of Penang into the Malayan Union, which was then replaced with the Federation of Malaya in 1948. At first, the impending annexation of the British colony of Penang into the vast Malay heartland proved unpopular among Penangites.[61] Partly due to concerns that George Town's free port status would be at risk in the event of Penang's absorption into Malaya's customs union, the Penang Secessionist Committee was founded in 1948 and attempted to avert Penang's merger with Malaya.[54][61] A petition at the time warned that the incorporation of Penang into Malaya would "reduce it to the churn of filth of a fishing village... trade assiduously built up during the last one and a half centuries will be turned to nothing, entailing untold monetary losses and hardship to the merchants in Penang".[54]

The secessionist movement was ultimately met with British disapproval.[62][63][64] To assuage the concerns raised by the secessionists, the British government guaranteed George Town's free port status and promised greater decentralisation. Meanwhile, municipal elections, which had been abolished in 1913, were reintroduced in 1951, further diminishing the secessionists' commitment to their cause.[5][62] Nine councillors were to be elected from George Town's three electoral wards, while the British High Commissioner held the power to appoint six more.[65] In 1956, George Town became Malaya's first fully-elected municipality and in the following year, it was granted city status by Queen Elizabeth II.[6][66] This made George Town the first city within the Malayan Federation, and by extension, Malaysia.[6][66]

Post-independence

[edit]

During the early years of Malaya's independence, George Town retained its free port status, which had been guaranteed by the British. The George Town City Council enjoyed full financial autonomy and by 1965, it was the wealthiest local government in Malaysia, with an annual revenue almost double that of the Penang state government.[65] This financial strength allowed the Labour-led city government to implement progressive policies, and to take control of George Town's infrastructure and public transportation. These included the maintenance of its own public bus service, as well as the construction of public housing schemes and the Ayer Itam Dam.[67][68]

However, longstanding political differences between the George Town City Council and the Alliance-controlled state government led to allegations of maladministration against the city government.[67][69] In response, Chief Minister of Penang, Wong Pow Nee, took over the powers of the George Town City Council in 1966.[69][70] Local government elections nationwide were also suspended in the aftermath of the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, never to be reinstated.[65]

The period of relative prosperity vis-à-vis the rest of Malaysia came to an end in 1969, when the Malaysian federal government rescinded George Town's free port status.[50][63] This sparked massive unemployment, brain drain and urban decay within the city.[71][72][73] The federal government also began channelling resources towards the development of Kuala Lumpur and Port Klang, leading to George Town's protracted decline.[50]

To revive Penang's fortunes, newly-elected Chief Minister Lim Chong Eu launched the Komtar project in 1974 and spearheaded the establishment of the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone (Bayan Lepas FIZ) which, at the time, was outside the city.[50][74] Although these were successful in transforming Penang into a tertiary-based economy, they also led to the decentralisation of the urban population as residents gravitated towards newer suburban townships closer to the Bayan Lepas FIZ.[73][74][75] The destruction of hundreds of shophouses and whole streets for the construction of Komtar further exacerbated the hollowing out of George Town.[50]

In 1974, the George Town City Council and the Penang Island Rural District Council were merged to form the Penang Island Municipal Council. This led to a prolonged debate over George Town's city status, in spite of Clause 3 of the Local Government (Merger of the City Council of George Town and the Rural District Council of Penang Island) Order, 1974, which stated that "the status of the City of George Town as a city shall continue to be preserved and maintained and shall remain unimpaired by the merger hereby effected".[76]

Renaissance

[edit]

George Town had benefitted from a real estate boom towards the end of the 20th century, but in 2001, the Rent Control Act was repealed, worsening the depopulation of the city's historical core and leaving colonial-era buildings in disrepair.[50][77][78] The city also suffered from incoherent urban planning, poor traffic management and a brain drain which left it without the expertise to regulate urban development and arrest its decline.[19][30]

In response, George Town's civil societies banded together and galvanised public support for the conservation of historic buildings, and to restore the city to its former glory.[77][79][80] Following subsequent heritage conservation efforts, a portion of the city centre was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.[13][77]

Widespread resentment over the city's decline also resulted in the then opposition Pakatan Rakyat bloc (now Pakatan Harapan) wresting power in Penang from the incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) administration in the 2008 state election.[77][81][82] The newly-elected state government took a more inclusive approach to heritage conservation and sustainable urban development, while concurrently pursuing economic diversification.[83][84][85] The city has since witnessed an economic rejuvenation, boosted by a growth in the private sector.[86][87]

George Town's jurisdiction was expanded by the Malaysian federal government to encompass the entirety of Penang Island and the surrounding islets in 2015.[10][88] This expansion resulted in an enlargement of the city government's manpower and responsibilities, as well as enhancing the regulation of heritage conservation.[89][90]

Geography

[edit]

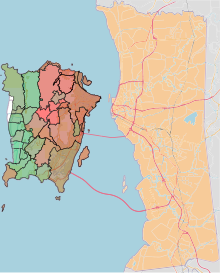

The jurisdiction of George Town covers an area of approximately 306 km2 (118 sq mi), encompassing the entirety of Penang Island and nine surrounding islets.[3][10][88] George Town is slightly more than two-fifths the size of Singapore.α The 295 km2 (114 sq mi) Penang Island has an uneven terrain with a mountainous topography down the middle.[28][92] The island's coastal plains are narrow, with the most extensive plain located at the northeastern cape, where the 25.5 km2 (9.8 sq mi) city centre is situated.[92] Over the centuries, the built-up area of George Town has expanded in three directions – along the island's northern coast, south down the eastern shoreline and towards Penang Hill to the west.[93]

The surrounding islets within George Town's jurisdiction are Jerejak, Andaman, Udini, Tikus, Lovers', Betong, Betong Kecil, Kendi and Rimau islands.[3] The riverine systems within the city include the Kluang, Dua, Glugor and Pinang rivers.[28] The Pinang River, which is 3.5 km (2.2 mi) long, flows through the city centre.[94]

Penang Hill, with a height of 833 m (2,733 ft), is the highest point in Penang, serving as a water catchment area and a green lung for the city.[95][96] In 2021, the 12,481 ha (124.81 km2) Penang Hill Biosphere Reserve, which includes the Penang Botanic Gardens and the 2,562 ha (25.62 km2) Penang National Park, was inscribed as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in recognition of the area's biodiversity.[95][97]

As land scarcity is a pressing issue in George Town, land reclamation has been extensively undertaken at high-demand areas, such as at Tanjong Tokong and Bayan Lepas.[91][98] Between 1960 and 2015, George Town expanded by more than 9 km2 (3.5 sq mi) due to land reclamation that altered much of the city's eastern shoreline.[98] In 2023, a massive reclamation project commenced off Batu Maung to build the 920 ha (9.2 km2) Silicon Island, envisioned as a new hub for high-tech manufacturing and commerce.[99] Reclamation projects to create Gurney Bay and the nearby mixed-use precinct of Andaman Island are also ongoing.[100][101]

Click link at the top right corner to zoom in.

Climate

[edit]George Town features a tropical rainforest climate, under the Köppen climate classification (Af). Weather forecast in George Town is served by the Penang Meteorological Office at Bayan Lepas, which acts as the primary weather forecast facility for northwestern Peninsular Malaysia.[102] The city experiences relatively consistent temperatures throughout the course of the year, with an average high of about 32 °C and an average low of 24°C.[103] It sees on average about 2,477 millimetres (97.5 in) of precipitation annually.[104] Its proximity to the island of Sumatra makes George Town susceptible to dust particles carried by wind from transient forest fires that cause the perennial Southeast Asian haze.[105]

| Climate data for George Town (Penang International Airport) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1934–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.2 (95.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.2 (97.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.1 (93.4) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.1 (93.4) |

36.2 (97.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.9 (89.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.8 (82.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.6 (76.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 80.3 (3.16) |

85.8 (3.38) |

145.5 (5.73) |

188.4 (7.42) |

229.1 (9.02) |

163.5 (6.44) |

189.8 (7.47) |

246.3 (9.70) |

316.4 (12.46) |

336.6 (13.25) |

232.8 (9.17) |

116.5 (4.59) |

2,331 (91.77) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 13.6 | 13.0 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 13.2 | 15.5 | 18.3 | 15.7 | 10.8 | 142.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 78 | 81 | 84 | 85 | 84 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 85 | 78 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 191 | 204 | 201 | 191 | 178 | 171 | 172 | 169 | 167 | 161 | 164 | 169 | 2,138 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[106] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Ogimet[107]Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity),[108] | |||||||||||||

Governance and politics

[edit]Local governance

[edit]Below: The City Hall, built in 1903 as a combination of Edwardian and Baroque architectural styles, has been listed as a national monument since 1982.[23]

In 1796, a committee was formed to record trade revenue, and another committee responsible for property valuation was established in 1800. The latter committee was assembled through an election of ratepaying representatives, making it the first political election ever held in the settlement.[5] Although the committees were organised ad hoc and lacked regulatory power, these early measures marked the beginning of a systematic approach to municipal governance in Penang.[5]

In 1856, the India Board, an administrative body of British India, passed Act No. XXVII, which mandated the appointment of Municipal Commissioners and taxation of the Straits Settlements.[109] A Municipal Commission for George Town came into being the following year.[5] In 1957, prior to Malaya's independence, Queen Elizabeth II granted George Town city status, making it the first city in the new nation.[6][66] By then, George Town had also become the first municipality in Malaya to have a fully-elected local government.[66] Following the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, local government elections across the country have been suspended since 1965.[5][65]

The Penang Island City Council (MBPP), headquartered in the City Hall, carries out the official administrative and legislative duties of the city. One of the two city governments in Penang, MBPP is led by a mayor, assisted by a secretary and 24 councillors who perform oversight responsibilities over 19 departments.[110][111] Each councillor is appointed by the Penang state government under an extendable one-year term.[112] As of 2023[update], one of the 24 councillor positions has been allocated to the city's non-governmental organisations (NGOs), while the remaining 23 are occupied by component parties of the ruling state government.[113] The mayor since 2023 is Rajendran P. Anthony, the second mayor of Indian descent in the city's history after D. S. Ramanathan and the first since 2015.[111][114]

MBPP's current urban planning strategy is set out in the Penang Island Local Plan 2030, first published in 2022.[3][115] The city government is responsible for municipal services including waste management, public maintenance and community service.[116] It is also involved in major infrastructural projects such as the Jalan Bukit Kukus Paired Road.[117] Since 2009, it has operated the Central Area Transit (CAT) bus service in collaboration with Rapid Penang.[118] In 2023, MBPP projected its estimated revenue at RM372.29 million and an estimated expenditure of RM405.17 million, which included allocations for smart city projects, economic growth, cleanliness, sustainability and urban mobility.[119]γ

After Pakatan Rakyat (predecessor to the incumbent Pakatan Harapan) was voted into power in 2008, the newly-elected state government attempted to reinstate local government elections within Penang.[120] Backed by strong support from George Town's NGOs, the Local Government Elections (Penang Island and Province Wellesley) Enactment was passed in 2012, which would have allowed city government elections for the first time since the 1960s. However, the Barisan Nasional-controlled federal government objected to the move and the Federal Court later ruled that local government elections are not within the purview of state governments.[120][121]

State and national representation

[edit]

George Town is the administrative capital of Penang. The offices of the Chief Minister of Penang and the Penang state government are located in Komtar, while the official residence of the Governor of Penang is located in Scotland Road.[33][122] Penang's legislature has been convened in the State Assembly Building in Light Street since 1959.[123]

George Town is represented by six Members of Parliament and 19 state constituencies.[85] Prior to 2023, state elections had been conducted simultaneously with nationwide general elections every five years.[85] Tanjong is the smallest parliamentary constituency in Malaysia by area.[124] Padang Kota is the least populated state constituency by population, while Pengkalan Kota is the densest in the country.[125] Batu Lancang has the largest proportion of Chinese residents in any state constituency.[125]

Due to George Town's predominantly Chinese population and the longstanding political consciousness, the city has been regarded as a stronghold for the incumbent Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.[126][127] As of 2023[update], non-Malays formed the majority in 15 out of the 19 state constituencies in George Town, particularly around the city centre.[85] In the 2023 state election, PH retained 17 of George Town's state constituencies, with the far-right Perikatan Nasional (PN) opposition bloc seizing two of the Malay-majority seats at the western edge of the city.[85]

Parliamentary constituencies[85]

State constituencies[85]

Judiciary

[edit]George Town is the judicial capital of Penang. The city's judicial system consists of the magistrate, sessions and the high court. The Penang High Court, the state's supreme judicial authority, is located in Light Street. Established in 1808, the high court is regarded as the birthplace of the modern Malaysian judiciary.[21][39] Notable lawyers who served the Penang High Court include Tunku Abdul Rahman, Cecil Rajendra and Karpal Singh.[23][128]

The city also has two magistrate and sessions courts serving the Northeast and Southwest districts respectively, with the former located in Light Street and the latter housed in Balik Pulau.[129] The Royal Malaysia Police is responsible for law enforcement within George Town, establishing a total of 22 police stations throughout the city as of 2022[update].[130][131] Traffic law enforcement is augmented by MBPP's traffic warden unit, the first unit of its kind outside Kuala Lumpur.[132]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 101,182 | — |

| 1921 | 123,069 | +21.6% |

| 1931 | 149,408 | +21.4% |

| 1947 | 189,068 | +26.5% |

| 1957 | 234,903 | +24.2% |

| 1970 | 269,247 | +14.6% |

| 1980 | 250,578 | −6.9% |

| 1991 | 219,603 | −12.4% |

| 2000 | 180,573 | −17.8% |

| 2010 | 198,298 | +9.8% |

| 2020β | 794,313 | +300.6% |

| Source: [11][133] | ||

According to the 2020 Malaysian census, George Town's population was 794,313, out of which 158,336 – or almost 20% – resided within the city centre.[11][134] With a population density of approximately 2,595.8/km2 (6,723/sq mi), George Town is also one of the most densely populated cities in Malaysia.[11][98] The city's identity has been largely shaped by centuries of intermingling between the various cultures on its shores.[37][54] The George Town Conurbation, which also covers Seberang Perai, and parts of neighbouring Kedah and Perak, was home to 2,844,214 residents as of 2020[update], making it the second largest metropolitan area in Malaysia after the Klang Valley.[11][135]

Ethnicities

[edit]

Historically, George Town has been a predominantly Chinese city. According to the 1891 Straits Settlements census, about 68% of George Town's population of 51,627 were ethnic Chinese.[136] As of 2020[update], Chinese formed more than half of the city's population.[11]

During British rule, the Chinese in George Town were categorised based on their dialects, such as Hokkien, Cantonese, Hainanese and Teochew, as well as place of birth.[136] In contrast to newer arrivals known colloquially as sinkheh, the Peranakan Chinese, descendants of mixed Malay and Chinese ancestries who had inhabited the Straits Settlements for generations, formed an influential group within the Chinese community.[37][61] They generally preferred Western education, and held leadership positions in some of George Town's commercial and community associations.[61][137] As the Peranakan Chinese tended to be more loyal to the British Crown than to China, they were also known as the "King's Chinese".[137][138] Although Malaysia's ethnic policies have effectively forced the Peranakan Chinese to identify themselves with the larger Chinese community, Peranakan Chinese culture still thrives in the city, visible in Straits Chinese architectural styles and dishes like asam laksa.[139]

The Bumiputeras, which include ethnic Malays and East Malaysian indigenous races like the Dayaks and Kadazans, collectively made up 31% of the city's population in 2020.[11][140][141] As of 2022[update], George Town has seen growing arrivals of Sabahan and Sarawakian natives migrating to the city for employment opportunities in sectors like manufacturing, healthcare and the civil service.[142] Ethnic Indians comprised another 8% of George Town's population.[11] Additionally, there are small but prominent Eurasian and Siamese enclaves such as Kampung Siam and Kampong Serani.[37][143][144]

Close to 8.5% of the city's population consisted of non-Malaysian citizens.[11] George Town's affordable living costs, natural destinations, advanced healthcare infrastructure, its established ecosystem of multinational companies (MNCs) and the widespread use of English have been cited as factors that made the city attractive to expatriates.[145][146] It has also been described by news outlets such as CNN as one of the best cities for retirement in the world.[147]

Throughout George Town's history as a cosmopolitan port of clearance and departure, it attracted a polyglot society consisting of various other communities such as Burmese, Acehnese, Arabs, Jews, Japanese and Armenians.[37][54] While most of these other communities no longer exist, they left their legacy to several landmarks and street names such as the Dhammikarama Burmese Temple, Armenian Street and the Jewish Cemetery.[37][148]

Languages

[edit]

Major languages in common use by George Town's multilingual, cosmopolitan society are Malay, English, Hokkien, Mandarin and Tamil.[37][150] Penang Hokkien, a local variant of the Hokkien dialect, is widely used as the unofficial lingua franca between the various ethnic groups in the city.[151][152]

During British rule, English was the official language in Penang, and was used as the medium of instruction in secular and mission schools.[37] The combination of Western education and the importance of English for global trade has created distinct English-speaking groups within the Chinese and Indian communities, in contrast to those who have received vernacular education.[37][150]

Like in the rest of Malaysia, Malay is currently Penang's official language. The Malays and Jawi Peranakans in the city often use Bahasa Tanjong, a variant of the Kedah Malay dialect that is slightly modified to suit the conditions of a cosmopolitan society.[153] Meanwhile, the Tamils form the bulk of George Town's Indian community.[37] Tamil is used as the medium of instruction in Tamil-medium primary schools.[150][154] Other Indian languages that are spoken in the city include Telugu and Punjabi.[37][155]

George Town's Chinese community uses a variety of Chinese dialects, including Teochew, Hakka and Cantonese.[37][150] Mandarin is the medium of instruction in Chinese schools, contributing to its more prevalent use among youths.[156] Originally a variant of the Southern Min group of languages, Penang Hokkien has absorbed numerous loanwords from Malay and English, yet another legacy of the Peranakan Chinese culture.[156][157] Although Penang Hokkien is still widely spoken within the city centre, its use has been waning in recent years in the face of the increasing prevalence of Mandarin and English.[151][156]

In 2008, the newly-elected Pakatan Rakyat state government introduced bilingual street signs throughout George Town.[149] These street signs display the names of streets in either English, Chinese, Tamil or Arabic alongside the official Malay language, highlighting the city's multilingual character.[158][159] However, this move was not without controversy, as the street signs occasionally became targets of vandalism by political extremists opposing the city's cosmopolitanism.[160][161]

Economy

[edit]As the capital city of Penang, one of the only four high-income territories in Malaysia, George Town has a diversified service sector. The city's economy is largely driven by manufacturing and services, particularly electronics and optical manufacturing, hospitality, wholesale and retail trade, logistics, finance, and real estate.[162] With at least 300 multinational companies (MNCs), the robust manufacturing sector has contributed to George Town emerging as Malaysia's leading exporter and one of the major destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country.[130][163][164] George Town is the core city of the George Town Conurbation, which had a GDP worth US$13.5 billion in 2010, the second largest economy in Malaysia after the Klang Valley.[135]

According to Euromonitor International in 2023, George Town exhibits the greatest potential among Malaysian cities for revenue growth.[165] The Economist Intelligence Unit had also reported that in 2015, the city contributed US$12,044 – or almost 8% – of Malaysia's personal disposable income in 2015, second only to Kuala Lumpur.[166] Knight Frank's 2016 rankings positioned George Town as Malaysia's most attractive destination for commercial property investment, surpassing even the federal capital.[167] George Town was rated a "Gamma −" level global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network in 2020, due to its capacity in "advanced producer services" – namely finance and insurance.[168][169] In 2024, George Town ranked 351st in the Oxford Economics Global Cities Index, the eighth highest within the ASEAN region and the second in Malaysia after Kuala Lumpur.[170] Additionally, the city has developed extensive logistical connections through the Penang International Airport and Swettenham Pier.

Manufacturing

[edit]

Following the revocation of George Town's free port status and the fall of the Alliance-led state government in 1969, newly-elected Chief Minister Lim Chong Eu sought to revamp Penang's economy and commissioned Robert R. Nathan Associates to formulate strategies.[72][74] The resulting Nathan Report of 1970 recommended an export-led growth strategy and the strengthening of linkages with the global economy.[74]

As a part of this economic transformation, the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone (Bayan Lepas FIZ) was established in 1972.[74] The zone has played a significant role in Penang's economic growth over the decades since.[72][81] It is regarded as the Silicon Valley of the East, home to more than 300 multinational companies (MNCs) including 39 Fortune 1000 companies.[163][172][171] Among the MNCs within the Bayan Lepas FIZ are technology firms such as AMD, Bosch, HP Inc., Intel, Motorola, Osram and Renesas.[173][174]

The electronics ecosystem and supply chain comprising both MNCs and large local companies (LLCs) have solidified George Town's position as a major destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) and Malaysia's top exporter.[164][130] In 2021, Penang captured RM74.4 billion in inbound FDI, with the Bayan Lepas FIZ contributing over 95%.[130][175] In 2022, the Penang International Airport (PIA), which lies adjacent to the zone, saw an estimated RM385 billion worth of exports, making it the largest exporter of all ports of entry in Malaysia.[164] The successful electronics manufacturing sector has also encouraged a growth in start-ups, driven by home-grown companies like Piktochart and DeliverEat.[176]

Finance

[edit]

George Town was once the financial centre of British Malaya. During the late 19th century, many international banks such as Standard Chartered, HSBC, and the Royal Bank of Scotland established themselves in the city, leading to the clustering of mercantile trade around the northern end of Beach Street.[21][33][177] Post-independence, George Town continues to function as the financial hub of northern Malaysia.[178] The city's financial and commercial precincts expanded around Northam Road and Pulau Tikus by the 1990s.[179][180]

The Penang Island City Council formally proposed the Central Business District (CBD) as one of the city's four economic zones in its Local Plan 2030, along with the Bayan Baru–Bayan Lepas, Tanjong Tokong–Tanjong Bungah and Batu Ferringhi–Teluk Bahang corridors.[3] Designated as a financial and banking district, the CBD covers a significant portion within the city centre up to the northern bank of the Pinang River, including existing financial precincts of Beach Street, Northam Road and Pulau Tikus, as well as a Business Improvement District (BIDS) around Komtar.[3][181] Apart from banking and ancillary services, the CBD is home to federal financial institutions like Bank Negara and the Employees Provident Fund.[151][182][183] In 2022, finance and ancillary services contributed 9.1% of Penang's GDP.[162]

Services

[edit]

George Town has traditionally been one of Malaysia's most popular tourist destinations. It has attracted influential personalities like Somerset Maugham, Rudyard Kipling, Noël Coward, Lee Kuan Yew and Queen Elizabeth II.[184][185][186] The city is recognised for its architecture and diverse cultures, natural attractions like beaches and hills, and its culinary scene.[187]

Unlike most cities in Malaysia, George Town is not solely dependent on air transportation for tourist arrivals. Swettenham Pier, the busiest port-of-call in Malaysia for cruise shipping, serves as a major entry point into the city along with PIA.[188] In addition to its role as a freight exporter, the PIA ranks as the third busiest airport in the country in passenger volume.[189]

Measures to promote economic diversification have led to George Town expanding tourism offerings in specific areas such as healthcare, business events, ecotourism and cruise arrivals.[190] The city is home to several private hospitals, contributing to Penang's emergence as the leading destination in Malaysia for medical tourism.[191][192][193] George Town is the country's second most popular destination for meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions (MICE) after Kuala Lumpur, with the industry had an economic impact of about RM1.3 billion throughout Penang in 2018.[194][195] Some of the major venues for business events within the city are SPICE Arena, Straits Quay and Prangin Mall.[196]

As the main shopping destination of northwestern Malaysia, George Town's retail scene includes shopping malls like Gurney Plaza, Gurney Paragon, 1st Avenue Mall, Straits Quay, Sunshine Central and Queensbay Mall. The city's traditional shophouses and markets continue to thrive, offering various local products unique to Penang such as nutmegs, Heong Peng and Tambun biscuits.[197][198]

In 2004, the Bayan Lepas FIZ and the adjacent township of Bayan Baru were accorded Multimedia Super Corridor Cyber City status, paving the way for George Town's growth as a shared services and outsourcing (SSO) hub.[199] By 2016, Penang attracted the second largest share of investments for global business services (GBS) within Malaysia after Kuala Lumpur, creating over 8,000 high-income jobs in the process.[200][201] Newer office spaces at Bayan Baru have attracted multinational companies including Cisco, Citigroup, Clarivate, Swarovski and Teleperformance to establish GBS offices at the area.[202][203][204]

Cityscape

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

In 2008, UNESCO designated nearly 260 ha (2.6 km2) within the city centre as a World Heritage Site.[13] Recognised for the British-era cityscape, the city centre is notable for its "unique architectural and cultural townscape without parallel anywhere in East and Southeast Asia", according to UNESCO.[13] Largely bounded by Transfer Road to the west and Prangin Road to the south, the UNESCO-protected site is further demarcated into a 109.38 ha (270.3-acre) core zone surrounded by a 150.04 ha (370.8-acre) buffer zone.[3][13][206]

The Penang Island City Council has officially identified 3,642 heritage buildings inside the UNESCO-demarcated zone.[3] Shophouses sit alongside Anglo-Indian bungalows, mosques, temples, churches, and European-style administrative and commercial complexes, shaping the city's multicultural framework.[207] Among the landmarks within the zone that feature various Asian architectural styles are the Khoo Kongsi, Kapitan Keling Mosque and Sri Mahamariamman Temple.[23] Elsewhere in the city, the influence of Siamese and Burmese cultures can be seen at places of worship like Wat Chayamangkalaram, Dhammikarama Burmese Temple and Kek Lok Si.[208]

Apart from the colonial-era architecture, George Town is also home to most of Penang's skyscrapers. The tallest skyscrapers in the city include the Komtar Tower, Marriott Residences and Muze @ PICC. There has been a surge in demand for residential high-rises at the suburbs since 2015, driven by the growing need for strata housing and the city's thriving economy.[209]

Parks

[edit]

Established in 1884 by botanist Nathaniel Cantley, the Penang Botanic Gardens was Malaysia's first botanical garden.[23] It is dedicated to botanical and horticultural research, as well as wildlife conservation within the area.[211] The botanical garden forms part of the Penang Hill Biosphere Reserve, recognised as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve since 2021.[95][97] Nearby, the City Park was opened in 1972 as a public recreational space in the aftermath of the 1969 race riots in Kuala Lumpur.[212]

Spanning 2,562 ha (25.62 km2) within the Penang Hill Biosphere Reserve, the Penang National Park covers 1,266 ha (12.66 km2) of coastal hills, meromictic lakes, mangroves, coral reefs, and turtle-nesting beaches like Pantai Kerachut, Pantai Mas, Teluk Kampi and Teluk Ketapang.[213] Gazetted by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks in 2003, this forest reserve has been earmarked by the Penang state government as a key eco-tourism destination within the city.[213][214]

Described as "a new iconic waterfront destination for Penang" by then Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng, Gurney Bay is a 24.28 ha (0.2428 km2) park being built on reclaimed land off Gurney Drive.[100] It is divided into four sections featuring a food and beverage (F&B) area, water gardens, a man-made beach and a coastal grove.[100][215] The first phase of Gurney Bay was opened to public in 2024.[210]

As part of efforts to create accessible green spaces and counter climate change within George Town, the Penang Island City Council is developing 18,000 ha (180 km2) of interconnecting parks and waterways throughout the city.[3][216] The Penang Green Connectors Project envisions ecological corridors that include 50 km (31 mi) of coastal parks and 65 km (40 mi) of riverine systems designated as "blue corridors", in addition to the construction of pedestrian and cycling paths in the city.[216]

Culture

[edit]Arts

[edit]

The Penang variant of the Chingay procession was introduced in George Town in 1919. It is characterised by the act of balancing gigantic flags on one's head or hands.[218] Formerly infused with rituals from the Chinese underworld, Chingay parades are now held annually in the city as a tourist attraction by itself and continue to be a major expression of the Penang Chinese identity.[219][220] George Town was also the birthplace of Bangsawan, a form of Malay theatre that incorporates Indian, Western, Islamic, Chinese and Indonesian influences.[221] Boria, another unique form of theatre that features singing accompanied by violin, maracas and tabla, was first performed in the city in the mid-19th century.[222]

Apart from these, George Town has emerged as a hub for the arts and culture scene in Malaysia. Since its inception in 2010, the George Town Festival is one of the major yearly arts events in Southeast Asia.[223] Held annually since 2011, the George Town Literary Festival won the International Literary Festival Award at the London Book Fair in 2018, the first such event from Southeast Asia to receive this honour.[224]

In 2012, Lithuanian artist Ernest Zacharevic created a series of murals showcasing local culture, inhabitants and lifestyles. The city is also adorned with 52 wrought iron caricatures and 18 wall murals that depict its history and the daily lives of the local community.[217] Additionally, art exhibitions are held at event spaces like the Hin Bus Depot and Sia Boey.[225][226]

Cuisine

[edit]George Town's culinary scene incorporates Malay, Chinese, Indian, Peranakan and Thai influences, evident in the range of available street food that includes char kway teow, asam laksa and nasi kandar.[227] Described by CNN as "the food capital of Malaysia", the city was also listed by Time and Lonely Planet as one of the best in Asia for street food.[227][228][229] According to Time in 2004, only in the city "could food this good be this cheap".[228] Robin Barton of the Lonely Planet described George Town as the "culinary epicentre of the many cultures that arrived after it was set up as a trading port in 1786, from Malays to Indians, Acehenese to Chinese, Burmese to Thais".[229]

Over the years, the city's culinary scene has expanded to include fine dining establishments, adding to its already diverse array of street food options.[230][231] In 2022, the Michelin Guide made its debut in Penang, in recognition of the state's "small-scale restaurants and street food that embodies Malaysia's distinctive streetside dining culture".[232] The 2024 edition of the Michelin Guide features 53 eateries throughout the city.[233]

Sports

[edit]

George Town is home to a variety of sports facilities. The 20,000-seater City Stadium serves as the home ground for Penang FC, while the SPICE Arena features an indoor arena and an aquatics centre.[234][235] Malaysia's oldest equestrian centre, the Penang Turf Club, is located within the city.[23] Additionally, investments have also been made on dedicated training facilities for badminton and squash.[236][237] George Town has played host to regional and international sports tournaments like the 2001 SEA Games, 2013 Women's World Open Squash Championship and Asia's first Masters Games in 2018.[238][239][240]

Some of the more significant annual sporting events in the city include the Penang International Dragon Boat Festival and the Penang Bridge International Marathon. The Penang International Dragon Boat Festival takes place every December and attracts participants from abroad.[241] The Penang Bridge International Marathon, which features the iconic Penang Bridge as its route, has also gained international recognition and attracted about 20,000 participants from 61 countries in 2023.[242]

Education

[edit]As of 2022[update], George Town is home to 111 primary schools and 49 secondary schools.[130][131] British colonial rule had encouraged the growth of mission schools throughout the city, including St. Xavier's Institution, St. George's Girls' School and Methodist Boys' School.[37] Founded in 1816, Penang Free School (PFS) is the oldest English school in Southeast Asia.[243]

In 1819, the first Chinese school in George Town was established, marking the start of Malaysia's modern Chinese education system.[244][245] While Chinese, English and mission schools have since been brought under the jurisdiction of the Malaysian Ministry of Education, the Penang state government also provides annual financial assistance to aid in the maintenance of these schools.[246] George Town is also home to 12 international and expatriate schools that offer either British, American or International Baccalaureate syllabuses.[130][131][247]

In 1969, Universiti Pulau Pinang was established as Malaysia's second university and the first public tertiary institution in George Town.[66][248] It was renamed Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) in 1972.[249] As of 2025[update], the university is ranked 146th in the QS World University Rankings, third in Malaysia after Universiti Malaya and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.[250] Most of the other tertiary institutions within the city are privately-run, including Wawasan Open University, Han Chiang University College of Communication, DISTED College and RCSI & UCD Malaysia Campus.[251] Headquartered at Gelugor, RECSAM is one of the 26 specialist institutions of the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization.[252]

In 2016, the state government launched Malaysia's first digital library within the grounds of PFS.[253] Conceptualised as a "library in a park" and a community space, the Penang Digital Library provides structured access to over 3,000 ebook titles.[253][254] Following the success of the Penang Digital Library, similar libraries have been built at other locations within both the city and Seberang Perai.[255]

Healthcare

[edit]

Healthcare in Penang is provided by a two-tier system made up of public and private hospitals. Administered and funded by the Malaysian Ministry of Health (MOH), the 1,100-bed Penang General Hospital within the city centre is the main tertiary referral hospital of northwestern Malaysia.[256] It is supported by the 81-bed Balik Pulau Hospital that serves the western part of the city.[257]

In addition, 13 private hospitals are scattered throughout George Town.[258] Operating independently of the MOH, private hospitals such as Penang Adventist Hospital, Loh Guan Lye Specialists Centre and Island Hospital have played a significant role in making Penang the top destination for medical tourists in Malaysia.[191][192] While public and private hospitals typically operate separately, there have been instances of public-private cooperation, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic which saw private hospitals sharing equipment and taking in non-COVID-19 patients in need of urgent medical procedures.[259]

Media

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]George Town was once the centre of Malaysia's print media. The country's first newspaper was the Prince of Wales Island Gazette, founded in the city in 1806.[260][261] The paper was shut down 21 years later, a victim of the stringent censorship that was prevalent in the early 19th century.[261] Greater press freedom eventually emerged by the middle of the century, concurrent with the perceived political freedom in Penang which stood in contrast to the stronger government apparatus in Singapore.[20][50][261]

Following Malaya's independence in 1957, several major dailies moved to Kuala Lumpur due to its importance as the country's administrative capital.[262] The Star, one of Malaysia's top English dailies, started as a regional newspaper that was first published in George Town in 1971.[263] In addition, George Town is home to the nation's oldest Chinese newspaper, Kwong Wah Yit Poh, which was established in 1910.[264]

Film and television

[edit]George Town's well-preserved colonial-era architecture has made the city a popular filming location for movies and television series that depict Asian culture.[265] Films and series that were shot within the city include Crazy Rich Asians, Anna and the King, Lust, Caution, The Little Nyonya and You Mean the World to Me; the latter was the first movie to be produced entirely in Penang Hokkien.[266] Additionally, George Town was featured as a pit-stop in The Amazing Race 16, The Amazing Race Asia 5 and The Amazing Race Australia 7.[267][268][269]

Transportation

[edit]

Land

[edit]George Town's oldest roads – Light, Beach, Chulia and Pitt streets – were arranged nearly at right angles to each other in a grid pattern.[28] Rapid urbanisation throughout the 20th century led to a gradual expansion of the city's road network.[28] George Town is physically connected to mainland Malay Peninsula by two road bridges – the 13.5 km (8.4 mi) Penang Bridge and the 24 km (15 mi) Second Penang Bridge.[270] Within the city, the Tun Dr Lim Chong Eu Expressway is an important thoroughfare that runs along its eastern seaboard, connecting the city centre with the two bridges and the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone.[271] The Federal Route 6 is a pan-island trunk road that circles the city, while the George Town Inner Ring Road functions as the main artery within the city centre.[272][273]

Public transportation

[edit]

George Town was formerly at the forefront of public transportation in Malaya. The first trams, originally powered by steam, were launched in the 1880s and gradually expanded throughout the settlement.[49] Although trams became obsolete by 1936, another colonial legacy, the trishaw, remains in use primarily for tourists.[49][275]

Public buses form the backbone of the city's public transportation system. Since 2007, Rapid Penang has been the primary public bus operator in the city.[276] As of 2023[update], it runs 25 routes throughout George Town, and two cross-strait routes between the city and Seberang Perai.[277]

Penang Hill Railway, a funicular railway to the peak of Penang Hill, is the only rail-based transportation system within the city. A cable car system is being built as of 2024[update] to reduce overreliance on the railway.[278] To further alleviate traffic congestion, which saw average daily traffic reaching 64,144 vehicles in 2019, the Penang state government embarked on the Penang Transport Master Plan, which envisions the introduction of urban rail systems throughout George Town.[279] In 2024, the Malaysian federal government announced a takeover of the Mutiara LRT line from the state government. This 29 km (18 mi) line is planned to connect the city with Seberang Perai and will link the city centre with the Penang International Airport.[280]

Efforts are also being undertaken to promote urban mobility by implementing pedestrianisation and providing cycling infrastructure.[281][282] George Town became the first city in Malaysia to operate a public bicycle-sharing service, with the inauguration of LinkBike in 2016.[282]

Air

[edit]

The Penang International Airport (PIA) is located 16 km (9.9 mi) south of the city centre. It serves as the primary airport for northwestern Malaysia. PIA is Malaysia's third busiest airport for passenger traffic, recording nearly 4.3 million passengers in 2022.[189] Within that same year, exports worth RM385 billion passed through PIA, making the airport the top contributor to Malaysia's export value.[164]

Sea

[edit]Swettenham Pier is one of the major entry points into George Town. In 2017, the pier saw 125 port calls by cruise ships, surpassing Port Klang as the busiest cruise shipping terminal in Malaysia.[188] It has attracted some of the world's largest cruise liners such as the Queen Mary 2 and also sees occasional port visits by warships.[285][286]

Prior to the completion of the Penang Bridge in 1985, the Penang ferry service was the only transportation link between George Town and mainland Seberang Perai.[287] At present, three ferries ply the Penang Strait between both cities daily, with the Raja Tun Uda Ferry Terminal serving as the dedicated docking facility in George Town.[288]

Utilities

[edit]George Town relies heavily on the Muda River, which forms the northern boundary between mainland Seberang Perai and Kedah, as its primary source of water. Treated water is delivered from the mainland to the island city via three sets of submarine pipelines.[289][290] The Penang Water Supply Corporation (PBAPP) is also responsible for managing the 11 reservoirs in George Town, including two at Ayer Itam and Teluk Bahang that act as strategic reserves for the surrounding suburbs in the event of dry weather and supply disruptions from the mainland.[96][291][292]

Electricity in George Town is supplied by Tenaga Nasional (TNB), the national power company. George Town's power supply is drawn from the mainland through three cross-strait cables that connect to the 330 MW Gelugor Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT) plant, the only power station in the city.[293][294][295] Due to the scheduled retirement of the Gelugor power plant in 2024, TNB is constructing a new RM500 million overhead power grid across the Penang Strait to cater to the anticipated demand up to 2030.[293][294] To reduce energy consumption, the Penang Island City Council and TNB replaced all 33,101 street lights throughout George Town with LED street lighting by 2023.[296]

In 2020, Penang had become the first Malaysian state to make the installation of fibre-optic communication infrastructure mandatory for all development projects.[297] In 2022, George Town saw the implementation of 5G, with the installation of the supporting spectrum infrastructure at 151 sites within the city.[298] The Penang International Airport became the first airport in Malaysia to offer public 5G services that year.[299] In 2024, DE-CIX inaugurated the Penang Internet Exchange (PIX), with internet traffic being routed through a data centre at Bayan Baru.[300][301]

International relations

[edit]George Town is home to a substantial contingent of foreign diplomatic missions. As of 2023[update], a total of 23 countries have either established consulates or appointed honorary consuls within the city. This list is based on information from the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, unless otherwise cited.[302]

Sister and friendship cities

[edit]George Town is also twinned with the following sister and friendship cities.

Sister cities

Friendship cities

Notable people

[edit]George Town was the birthplace of prominent Malaysian and Singaporean personalities and professionals, including:

- Wu Lien-teh (1879–1960), physician and inventor of the respiratory mask[313]

- Hon Sui Sen (1916–1983), former cabinet minister in Singapore[314]

- Wee Chong Jin (1917–2005), first Chief Justice of Singapore[315]

- P. Ramlee (1929–1973), actor, filmmaker, musician, composer and icon of Malay-language entertainment[316]

- Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (born 1939), fifth Prime Minister of Malaysia[317]

- Karpal Singh (1940–2014), lawyer, politician and former national chairman of the Democratic Action Party[318]

- Jimmy Choo (born 1948), fashion designer knighted with the Order of the British Empire[319]

- David Arumugam (born 1950), singer and founder of the pop band Alleycats[320]

- Khaw Boon Wan (born 1952), former cabinet minister in Singapore[321]

- Sultan Nazrin Shah (born 1956), reigning monarch of the neighbouring state of Perak[322]

- Ooi Keat Gin (born 1959), academician and historian[323]

- Saw Teong Hin (born 1962), film director[324]

- Nicol David (born 1983), former world number one female squash player[325]

- Chan Peng Soon (born 1988), Malaysian badminton player and 2016 Olympic silver medallist[326]

- Loh Kean Yew (born 1997), Singaporean badminton player[327]

Notes

[edit]- ^α Singapore's land mass is approximately 734 km2 (283 sq mi).[328]

- ^β The massive jump in population is attributable to the expansion of George Town's jurisdiction to its present-day city limits in 2015. See #Renaissance.[10][88]

- ^γ As of 2021[update], 1 Malaysian ringgit was equivalent to 0.24 US dollar.[329]

References

[edit]- ^ Mike Aquino (30 August 2012). "Exploring Georgetown, Penang". Asian Correspondent. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Logo". Penang Island City Council. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Draf Rancangan Tempatan Pulau Pinang (Pulau) 2030 Jilid 1". Penang Island City Council.

- ^ a b c d e f Samuel Wee, Tien Wang (1992). "British Strategic Interests in the Straits of Malacca 1786–1819" (PDF). Simon Fraser University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Koay Su Lin, Steven Sim (2014). "A History of Local Elections in Penang Part I: Democracy Comes Early". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Penang's Big Day—What a Day!". The Straits Times. 2 January 1957. p. 1. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Opalyn Mok (31 March 2015). "Council President Now Penang's First Mayor". Malay Mail. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Mayor's Profile". Penang Island City Council. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "City Secretary (Chief Digital Officer (CDO))". Penang Island City Council. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Looi, Sue Chern (25 March 2015). "George Town A City Again". The Edge. Archived from the original on 26 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Key Findings of Population and Housing Census of Malaysia 2020" (pdf) (in Malay and English). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. ISBN 978-967-2000-85-3.

- ^ Jessica Chan (30 November 2000). "Asiaweek's Top Ten Cities of Asia". Asiaweek. Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Ooi, Keat Gin (2010). The A to Z of Malaysia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780810876415.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2017). The Concise Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192556462.

- ^ "Penaga Laut trees are Back in George Town". The Star. 28 July 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Sanjay, CS (16 July 2015). "The Right Spelling is George Town". The Star. Archived from the original on 22 February 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Tennant, Paul (March 1973). "The Abolition of Elective Local Government in Penang". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 4 (1): 72–87. doi:10.1017/S0022463400016428. ISSN 1474-0680. S2CID 159521756. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Gwynn (2008). Contested Space: Cultural Heritage and Identity Reconstructions : Conservation Strategies Within a Developing Asian City. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783825813666.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, Su Lin (2016). Cities in Motion: Urban Life and Cosmopolitanism in Southeast Asia, 1920–1940. University of Cambridge. ISBN 9781107108332.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Langdon, Marcus (2014). George Town's Historic Commercial and Civic Precincts. George Town World Heritage Incorporated (published 2015). ISBN 9789671228128.

- ^ Merican, Ahmad Murad (29 October 2021). "The 1786 Acquisition of Pulau Pinang: Unveiling the Light Letters, Revisiting Legal History Case Materials and R. Bonney's Kedah 1771–1821" (PDF). Universiti Sains Malaysia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hockton, Keith (2012). Penang: An Inside Guide to Its Historic Homes, Buildings, Monuments and Parks. MPH Group. ISBN 978-967-415-303-8.

- ^ Ooi, Keat Gin (2010). The A to Z of Malaysia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780810876415.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2017). The Concise Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192556462.

- ^ a b Pampus, Mareike (September 2021). "Multiple Motives and a Malleable Middleman: The Founding of George Town (Malaysia)". Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg.

- ^ Shennan, Margaret (2000). Out in the Midday Sun: The British in Malaya, 1880-1960. John Murray. ISBN 9780719557163.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhao, Long (2 December 2018). "The Townscape Evolution of Historic Port Settlement of George Town, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia" (PDF). University of Putra Malaysia. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Fadzlin Bakri, Aidatul (October 2018). "Negotiating Identities and 'Sense of Place' in a World Heritage City: The Case of George Town, Penang, Malaysia" (PDF). University of Birmingham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ a b Sue-Ching Jou, Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao, Natacha Aveline-Dubach (2014). Globalization and New Intra-Urban Dynamics in Asian Cities. National Taiwan University. ISBN 9789863500216.

- ^ Ashley Jackson (November 2013). Buildings of Empire. OUP Oxford. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-958938-8. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ Ooi, Kee Beng (2014). "When Penang Became a Spice Island". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Khoo, Su Nin (2007). Streets of George Town, Penang. Areca Books. ISBN 978-983-9886-00-9.

- ^ Ludher, Swaran (2015). They Came to Malaya. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781503500365.

- ^ Tan, Soo Chye (1950). "A Note on Early Legislation in Penang". Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1 (151): 100–107. JSTOR 41559485. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Tan 1950, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Keat Gin, Ooi (2015). "Disparate Identities: Penang from a Historical Perspective, 1780–1941" (PDF). Kajian Malaysia – Journal of Malaysian Studies. 33 (2). Universiti Sains Malaysia: 27–52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Kyshe, Norton (1885). Cases Heard and Determined in Her Majesty's Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements, 1808–1884. Vol. I, Civil Cases. Vol. 1. Singapore and Straits Print. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ a b The Malaysian Judiciary: Yearbook 2016 (PDF). Federal Court of Malaysia. 2016. p. XV. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Singapore Becomes Admin Centre of the Straits Settlements". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b Jaime Koh. "Straits Settlements". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 13 January 2024. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ a b Wong, Yee Tuan (2015). Penang Chinese Commerce in the 19th Century: The Rise and Fall of the Big Five. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. ISBN 978-981-4515-02-3.

- ^ a b Ooi, Giok Ling (2 September 1991). "British Colonial Health Care Development and the Persistence of Ethnic Medicine in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore" (PDF). National University of Singapore. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 14 February 2024 – via Kyoto University.

- ^ "The Disturbances at Penang". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 September 1867. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2017 – via Trove.

- ^ Wong, Chun Wai (20 April 2013). "A cowboy town that was old Penang". The Star. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Straits Settlements". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Turnbull, C. M. "The Penang Story" (PDF). Penang's Changing Role in the Straits Settlements, 1826–1946. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Asian Studies". Government Legislation for Chinese Secret Societies in the Straits Settlements in the Late 19th. Century.

- ^ a b c Francis, Ric (2006). Penang Trams, Trolleybuses & Railways: Municipal Transport History, 1880s–1963. Areca Books. ISBN 9789834283407.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Daniel Goh, P. S. (2014). "Between History and Heritage: Post-Colonialism, Globalisation, and the Remaking of Malacca, Penang and Singapore" (PDF). Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Chinese Hero's Memory Burns Bright in Penang House". Reuters. 21 January 2007. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Sun Yat Sen". National Library Board. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Ajay Kamalakaran (20 May 2015). "Battle of Penang: When Malay Fishermen Rescued Russian Sailors". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Barber, Andrew (2010). Penang At War : A History of Penang During and Between the First and Second World Wars 1914–1945. AB&B.

- ^ "Penang Evacuated – British Garrison Withdrawn New Jap Thrusts in Malaya London, December 19 – Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA : 1905–1952) – 20 December 1941". Northern Times. 20 December 1941. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Bayly, Christopher (2005). Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941–1945. Harvard University.

- ^ B. Frank, Richard (2020). Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War: July 1937-May 1942. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9781324002116.

- ^ Stevens, David. "German U-Boat Operations in Australian Waters". Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Eugene Quah (December 2023). "When Penang Was an Axis Submarine Base". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 27 December 2023. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ Paul H. Kratoska (1998). The Japanese Occupation of Malaya: A Social and Economic History. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-85065-284-7. Archived from the original on 16 March 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Koay, Su Lin (2016). "Penang: The Rebel State (Part One)". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ a b Koay, Su Lin (1 October 2016). "Penang: The Rebel State (Part Two)". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b Christie, Clive (1998). A Modern History of Southeast Asia: Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-354-5.

- ^ Sopiee, Mohd. Noordin (7 April 2011). "The Penang Secession Movement, 1948–1951". Cambridge University Press. 4: 52–71. doi:10.1017/S0022463400016416. S2CID 154817139. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Abdullah, Saifuddin. "George Town: Malaysia's First Local Democracy". Penang Institute. Archived from the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Wong, Chun Wai (5 October 2013). "George Town's First Mayor Ramanathan was a Fiery Man, Politician, Educationist and Unionist". The Star. Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ a b "REFSA Quarterly issue 1 2015" (PDF). REFSA. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Urban Transport Study in Greater Metropolitan Areas of George Town, Butterworth and Bukit Mertajam" (PDF). Japan International Cooperation Agency. January 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Minister to Take Over City Council". The Straits Times. 10 June 1966. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Khor, Cheang Kee (3 August 1966). "City Hall Drama". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ Singh, Chet; Rasiah, Rajah; Wong, Yee Tuan (2019). From Free Port to Modern Economy: Economic Development and Social Change in Penang, 1969 to 1990. Penang Institute. ISBN 9789814843966.

- ^ a b c Ooi, Kee Beng (December 2009). "Tun Lim Chong Eu: The Past is Not Passé". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ a b Evelyn Teh (July 2016). "Where the Sea Meets the City is Where the World Meets Penang". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Athukorala, Prema-chandra. "Growing with Global Production Sharing: The Tale of Penang Export Hub, Malaysia" (PDF). Australian National University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ Nancy Duxbury, W.F. Garrett-Petts, David MacLennan (2015). Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry. Routledge. ISBN 9781317588016.

- ^ Goh, Ban Lee (February 2010). "Remember the City Status of George Town". Penang Monthly. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Li, Ho Fai (September 2011). "The Politics of Heritage Conservation in a Southeast Asian Postcolonial City: The Case of Georgetown in Penang, Malaysia" (PDF). Chinese University of Hong Kong. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Rananawa, Arjuna (30 March 2000). "A City at a Crossroad". CNN. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ Ng, Su-Ann (7 November 2004). "Penang Losing Its Tourism Lustre". The Star. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Penang – Who Should Stop the Rot?". Malaysiakini. 16 December 2004. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ a b Ooi, Kee Beng (2010). Pilot Studies for a New Penang. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814279697.

- ^ Saravanamuttu Jayaratnam, Lee Hock Guan, Ooi Kee Beng (2008). March 8: Eclipsing May 13. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812308962.

- ^ "From Port City to World Heritage Site: Case Study of George Town (Malaysia)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.