Southampton Island

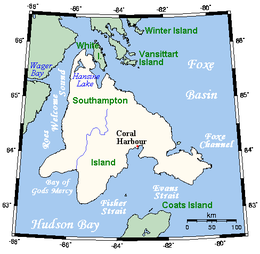

Map of the Southampton Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Hudson Bay at Foxe Basin |

| Coordinates | 64°20′N 084°40′W / 64.333°N 84.667°W[1] |

| Archipelago | Arctic Archipelago |

| Area | 41,214 km2 (15,913 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 34th |

| Highest elevation | 625 m (2051 ft) |

| Highest point | Mathiassen Mountain |

| Administration | |

Canada | |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Region | Kivalliq |

| Largest settlement | Coral Harbour (pop. 1035[2]) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1035 (2021 Canadian census) |

| Ethnic groups | Inuit |

Southampton Island (Inuktitut: Shugliaq)[3] is a large island at the entrance to Hudson Bay at Foxe Basin. One of the larger members of the Arctic Archipelago, Southampton Island is part of the Kivalliq Region in Nunavut, Canada. The area of the island is stated as 41,214 km2 (15,913 sq mi) by Statistics Canada.[4] It is the 34th largest island in the world and Canada's ninth largest island. The only settlement on Southampton Island is Coral Harbour (population 1,035, 2021 Canadian census),[5] called Salliq in Inuktitut.

Southampton Island is one of the few Canadian areas, and the only area in Nunavut, that does not use daylight saving time.

History

[edit]

Historically speaking, Southampton Island is famous for its now-extinct inhabitants, the Sadlermiut (modern Inuktitut Sallirmiut "Inhabitants of Salliq"), who were the last vestige of the Tuniit or Dorset. The Tuniit, a pre-Inuit culture, officially went ethnically and culturally extinct in 1902-03[6] when infectious disease killed all of the Sallirmiut in a matter of weeks.

The island's first recorded visit by Europeans was in 1613 by Welsh explorer Thomas Button.[7]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the island was repopulated by Aivilingmiut from Naujaat and Chesterfield Inlet, influenced to do so by whaler Captain George Comer and others. Baffin Islanders arrived 25 years later. John Ell, who as a young child travelled with his mother Shoofly on Comer's schooners, eventually became the most famous of Southampton Island's re-settled population.[8]

The Native Point archaeological site at the mouth of Native Bay is the largest Sadlermiut site on the island.[9]

Geology

[edit]Southampton Island does have geological resources that are of scientific and industrial interest.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

However, full knowledge of the island is still lacking according to the Nunavut government.[16]

The current level of basic geoscience available for the Southampton region is inadequate to meet current exploration demands. Regional scale mapping of the bedrock geology of Southampton Island has not occurred since 1969. Only the most general of rock distinctions are made on the existing geological map, and only a very rudimentary understanding of the surficial geology exists. Currently there is no publicly available, regional-scale surficial (till) geochemical data which is essential for understanding exploration potential for metals and diamonds.

Gallery

[edit]-

Capt. Capt. George Comer's 1913 map of Southampton.

-

Satellite photo montage of Southampton Island

Geography

[edit]It is separated from the Melville Peninsula by Frozen Strait.[17] Other waterways surrounding the island include Roes Welcome Sound to the west, Bay of Gods Mercy in the southwest, Fisher Strait in the south, Evans Strait in the southeast, and Foxe Channel in the east.

Hansine Lake is located in the far north. Bell Peninsula is located in the southeastern part of the island.[18] Mathiassen Mountain, a member of the Porsild Mountains, is the island's highest peak. The island's shape is vaguely similar to that of Newfoundland.

Climate

[edit]Southampton Island has a severe subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc) which transitions into a tundra climate (ET). Like almost all of Nunavut, Southampton Island is entirely above the tree line. Coral Harbour has never gone above freezing in January, February and March (although the latter has recorded 0.0 °C (32.0 °F). Due to the frozen nature of Hudson Bay, there is a severe seasonal lag until June, especially compared to more continental areas such as Fairbanks despite much sunshine and perpetual twilight at night. Due to the drop of solar strength and the absence of warm water even in summer, temperatures still drop off very fast as September approaches. Cold extremes are severe, but in line with many areas even farther south in Canada's interior.

| Climate data for Coral Harbour (Coral Harbour Airport) WMO ID: 71915; coordinates 64°11′36″N 83°21′34″W / 64.19333°N 83.35944°W; elevation: 62.2 m (204 ft); 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1933−present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 0.2 | −1.9 | −0.5 | 4.4 | 8.9 | 23.1 | 32.8 | 30.1 | 19.9 | 7.6 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 32.8 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

23.5 (74.3) |

28.0 (82.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −24.9 (−12.8) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−19.2 (−2.6) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −29.0 (−20.2) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −33.2 (−27.8) |

−33.7 (−28.7) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −52.8 (−63.0) |

−51.4 (−60.5) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−39.4 (−38.9) |

−31.1 (−24.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−17.2 (1.0) |

−34.4 (−29.9) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

−48.9 (−56.0) |

−52.8 (−63.0) |

| Record low wind chill | −69.5 | −69.3 | −64.3 | −55.1 | −39.7 | −23.2 | −8.2 | −11.8 | −23.7 | −43.7 | −54.8 | −64.2 | −69.5 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.5 (0.37) |

7.0 (0.28) |

11.2 (0.44) |

18.2 (0.72) |

19.0 (0.75) |

27.6 (1.09) |

34.1 (1.34) |

59.4 (2.34) |

45.4 (1.79) |

33.8 (1.33) |

22.9 (0.90) |

14.8 (0.58) |

302.9 (11.93) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.02) |

4.3 (0.17) |

20.8 (0.82) |

34.1 (1.34) |

58.9 (2.32) |

36.7 (1.44) |

7.2 (0.28) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

163.0 (6.42) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.6 (3.8) |

7.1 (2.8) |

11.3 (4.4) |

18.2 (7.2) |

14.9 (5.9) |

6.9 (2.7) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (0.2) |

8.6 (3.4) |

26.7 (10.5) |

22.9 (9.0) |

14.8 (5.8) |

141.6 (55.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.5 | 6.7 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 125.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 12.5 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 43.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 8.6 | 6.6 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 13.1 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 87.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1500 LST) | 67.4 | 66.4 | 69.2 | 74.5 | 80.3 | 73.1 | 62.8 | 69.1 | 75.8 | 85.5 | 79.7 | 72.0 | 73.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.9 | 112.1 | 187.4 | 240.2 | 239.9 | 262.2 | 312.3 | 220.4 | 109.8 | 70.8 | 47.9 | 18.8 | 1,859.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22.4 | 47.0 | 51.6 | 53.2 | 42.0 | 41.9 | 51.2 | 43.3 | 27.9 | 23.3 | 24.3 | 13.9 | 36.8 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[19] (rain/rain days, snow/snow days, precipitation/precipitation days and sun 1981–2010)[20] | |||||||||||||

Fauna

[edit]East Bay Migratory Bird Sanctuary and Harry Gibbons Migratory Bird Sanctuary are located on the island and are important breeding sites for the lesser snow goose (Anser caerulescens caerulescens). The island is also the site of two Important Bird Areas (IBAs), the Boas River wetlands in the southwest and East Bay/Native Bay in the southeast. Both host large summer colonies of the lesser snow goose, together comprising over 10% of the world's snow goose population, with Boas River site alone hosting over 500.000 individuals nesting there. Smaller, but also important, are the colonies of the brent goose (Branta bernicla) and numerous other polar bird species there.[21][22] Southampton Island is one of two main summering grounds known for bowhead whales in Hudson Bay.[23][24][25]

References

[edit]- ^ "Southampton Island". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ "Census Profile". 2.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ^ Issenman, Betty. Sinews of Survival: The living legacy of Inuit clothing. UBC Press, 1997. pp252-254

- ^ Statistics Canada Archived 2004-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), Nunavut". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Briggs, Jean L.; J. Garth Taylor. "The Canadian Encyclopedia: Sadlermiut Inuit". Historica Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ^ Christy, Miller (1894). The voyages of Captain Luke Foxe of Hull, and Captain Thomas James of Bristol, in search of a northwest passage, in 1631-32; with narratives of the earlier northwest voyages of Frobisher, Davis, Weymouth, Hall, Knight, Hudson, Button, Gibbons, Bylot, Baffin, Hawkridge, and others. London: Hakluyt Society.

related:STANFORD36105004846502.

- ^ Rowley, Graham (1996-06-11). Cold comfort: my love affair with the Arctic. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-7735-1393-0. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ^ "History". edu.nu.ca. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "New Insights into Ordovician Oil Shales of Southampton Island" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- ^ "Information archivée dans le Web" (PDF). publications.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Information archivée dans le Web" (PDF). publications.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Industrial Limestone Resources, Southampton Island" (PDF). nunavutminingsymposium.ca. Retrieved 19 April 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Faculté de foresterie, de géographie et de géomatique" (PDF). www.ffgg.ulaval.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 19, 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ "Information archivée dans le Web" (PDF). publications.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Southampton Island Integrated Geoscience (Siig) Project Plan/Description[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Frozen Strait". The Columbia Gazetteer of North America. 2000. Archived from the original on 2005-05-22. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Mathiasen Mountain Nunavut". bivouac.com. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ^ "Coral Harbour Nunavut". Canadian Climate Normals 1991–2020. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ "Coral Harbour A". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Climate ID: 2301000. Archived from the original on July 10, 2024. Retrieved 2019-01-24.

- ^ "Boas River and associated wetlands (NU022)". Important Bird Areas. IBA Canada. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ "East Bay/Native Bay (NU023)". Important Bird Areas. IBA Canada. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Bowhead Whale Balaena mysticetus (PDF). COSEWIC. 2005. ISBN 0-662-40573-0.

- ^ "Coral Harbour - Land and Wildlife". www.coralharbour.ca. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ http://www.nwmb.com/en/public-hearings/2008/mar-06-2008-level-of-tah-for-bowhead-whales/552-tab16-arctic-2000/file [bare URL PDF]

Further reading

[edit]- Bird, J. Brian. Southampton Island. Ottawa: E. Cloutier, 1953.

- Brack, D. M. Southampton Island Area Economic Survey With Notes on Repulse Bay and Wager Bay. Ottawa: Area & Community Planning Section, Industrial Division, Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1962.

- Mathiassen, Therkel. Contributions to the Physiography of Southampton Island. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, 1931.

- Parker, G. R. An Investigation of Caribou Range on Southampton Island, Northwest Territories. Ottawa: Information Canada, 1975.

- Pickavance, J. R. 2006. "The Spiders of East Bay, Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada". Arctic. 59, no. 3: 276–282.

- Popham RE. 1953. "A Comparative Analysis of the Digital Patterns of Eskimo from Southampton Island". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 11, no. 2: 203–13.

- Popham RE, and WD Bell. 1951. "Eskimo crania from Southampton Island". Revue Canadienne De Biologie / ̐ưedit̐ưee Par L'Universit̐ưe De Montr̐ưeal. 10, no. 5: 435–42.

- Sutton, George Miksch, and John Bonner Semple. The Exploration of Southampton Island. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, 1932.

- Sutton, George Miksch. The Birds of Southampton Island. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, 1932.

- VanStone, James W. The Economy and Population Shifts of the Eskimos of Southampton Island. Ottawa: Northern Co-ordination and Research Centre, Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1959.