Felix Klein

Felix Klein | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 April 1849 |

| Died | 22 June 1925 (aged 76) |

| Alma mater | University of Bonn |

| Known for | Erlangen program Klein bottle Beltrami–Klein model Klein's Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences Kleinian group Klein four-group |

| Awards | De Morgan Medal (1893) Copley Medal (1912) Ackermann–Teubner Memorial Award (1914) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions | Universität Erlangen Technische Hochschule München Universität Leipzig Georg-August-Universität Göttingen |

| Doctoral advisors | Julius Plücker and Rudolf Lipschitz |

| Doctoral students | List Ludwig Bieberbach Maxime Bôcher Oskar Bolza Max Brückner Frank Nelson Cole Friedrich Dingeldey Henry B. Fine Erwin Freundlich Robert Fricke Philipp Furtwängler Axel Harnack Mellen Haskell Adolf Hurwitz Edward Kasner Ferdinand von Lindemann Alexander Ostrowski Julio Rey Pastor Hermann Rothe Friedrich Schilling Virgil Snyder Edward Van Vleck Walther von Dyck Adolf Weiler Henry Seely White Alexander Witting Grace Chisholm Young |

| Other notable students | Edward Kasner |

Felix Christian Klein (German: [klaɪn]; 25 April 1849 – 22 June 1925) was a German mathematician and mathematics educator, known for his work in group theory, complex analysis, non-Euclidean geometry, and the associations between geometry and group theory. His 1872 Erlangen program classified geometries by their basic symmetry groups and was an influential synthesis of much of the mathematics of the time.

During his tenure at the University of Göttingen, Klein was able to turn it into a center for mathematical and scientific research through the establishment of new lectures, professorships, and institutes. His seminars covered most areas of mathematics then known as well as their applications. Klein also devoted considerable time to mathematical instruction, and promoted mathematics education reform at all grade levels in Germany and abroad. He became the first president of the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction in 1908 at the Fourth International Congress of Mathematicians in Rome.

Life

[edit]

Felix Klein was born on 25 April 1849 in Düsseldorf,[1] to Prussian parents. His father, Caspar Klein (1809–1889), was a Prussian government official's secretary stationed in the Rhine Province. His mother was Sophie Elise Klein (1819–1890, née Kayser).[2] He attended the Gymnasium in Düsseldorf, then studied mathematics and physics at the University of Bonn,[3] 1865–1866, intending to become a physicist. At that time, Julius Plücker had Bonn's professorship of mathematics and experimental physics, but by the time Klein became his assistant, in 1866, Plücker's interest was mainly geometry. Klein received his doctorate, supervised by Plücker, from the University of Bonn in 1868.

Plücker died in 1868, leaving his book concerning the basis of line geometry incomplete. Klein was the obvious person to complete the second part of Plücker's Neue Geometrie des Raumes, and thus became acquainted with Alfred Clebsch, who had relocated to Göttingen in 1868. Klein visited Clebsch the next year, along with visits to Berlin and Paris. In July 1870, at the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War, he was in Paris and had to leave the country. For a brief time he served as a medical orderly in the Prussian army before being appointed Privatdozent (lecturer) at Göttingen in early 1871.

The University of Erlangen appointed Klein professor in 1872, when he was only 23 years old.[4] For this, he was endorsed by Clebsch, who regarded him as likely to become the best mathematician of his time. Klein did not wish to remain in Erlangen, where there were very few students, and was pleased to be offered a professorship at the Technische Hochschule München in 1875. There he and Alexander von Brill taught advanced courses to many excellent students, including Adolf Hurwitz, Walther von Dyck, Karl Rohn, Carl Runge, Max Planck, Luigi Bianchi, and Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro.

In 1875, Klein married Anne Hegel, granddaughter of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[5]

After spending five years at the Technische Hochschule, Klein was appointed to a chair of geometry at Leipzig University. His colleagues included Walther von Dyck, Rohn, Eduard Study and Friedrich Engel. Klein's years at Leipzig, 1880 to 1886, fundamentally changed his life. In 1882, his health collapsed and he battled with depression for the next two years.[6] Nevertheless, his research continued; his seminal work on hyperelliptic sigma functions, published between 1886 and 1888, dates from around this period.

Klein accepted a professorship at the University of Göttingen in 1886. From then on, until his 1913 retirement, he sought to re-establish Göttingen as the world's prime center for mathematics research. However, he never managed to transfer from Leipzig to Göttingen his own leading role as developer of geometry. He taught a variety of courses at Göttingen, mainly concerning the interface between mathematics and physics, in particular, mechanics and potential theory.

The research facility Klein established at Göttingen served as model for the best such facilities throughout the world. He introduced weekly discussion meetings, and created a mathematical reading room and library. In 1895, Klein recruited David Hilbert from the University of Königsberg. This appointment proved of great importance; Hilbert continued to enhance Göttingen's primacy in mathematics until his own retirement in 1932.

Under Klein's editorship, Mathematische Annalen became one of the best mathematical journals in the world. Founded by Clebsch, it grew under Klein's management, to rival, and eventually surpass Crelle's Journal, based at the University of Berlin. Klein established a small team of editors who met regularly, making decisions in a democratic spirit. The journal first specialized in complex analysis, algebraic geometry, and invariant theory. It also provided an important outlet for real analysis and the new group theory.

In 1893, Klein was a major speaker at the International Mathematical Congress held in Chicago as part of the World's Columbian Exposition.[7] Due partly to Klein's efforts, Göttingen began admitting women in 1893. He supervised the first Ph.D. thesis in mathematics written at Göttingen by a woman, by Grace Chisholm Young, an English student of Arthur Cayley's, whom Klein admired. In 1897, Klein became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[8]

Around 1900, Klein began to become interested in mathematical instruction in schools. In 1905, he was instrumental in formulating a plan recommending that analytic geometry, the rudiments of differential and integral calculus, and the function concept be taught in secondary schools.[9][10] This recommendation was gradually implemented in many countries around the world. In 1908, Klein was elected president of the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction at the Rome International Congress of Mathematicians.[11] Under his guidance, the German part of the Commission published many volumes on the teaching of mathematics at all levels in Germany.

The London Mathematical Society awarded Klein its De Morgan Medal in 1893. He was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1885, and was awarded its Copley Medal in 1912. He retired the following year due to ill health, but continued to teach mathematics at his home for several further years.

Klein was one of ninety-three signatories of the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, a document penned in support of the German invasion of Belgium in the early stages of World War I.

He died in Göttingen in 1925.

Work

[edit]

Klein's dissertation, on line geometry and its applications to mechanics, classified second degree line complexes using Weierstrass's theory of elementary divisors.

Klein's first important mathematical discoveries were made in 1870. In collaboration with Sophus Lie, he discovered the fundamental properties of the asymptotic lines on the Kummer surface. They later investigated W-curves, curves invariant under a group of projective transformations. It was Lie who introduced Klein to the concept of group, which was to have a major role in his later work. Klein also learned about groups from Camille Jordan.[12]

Klein devised the "Klein bottle" named after him, a one-sided closed surface which cannot be embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space, but it may be immersed as a cylinder looped back through itself to join with its other end from the "inside". It may be embedded in the Euclidean space of dimensions 4 and higher. The concept of a Klein Bottle was devised as a 3-Dimensional Möbius strip, with one method of construction being the attachment of the edges of two Möbius strips.[13]

During the 1890s, Klein began studying mathematical physics more intensively, writing on the gyroscope with Arnold Sommerfeld.[14] During 1894, he initiated the idea of an encyclopedia of mathematics including its applications, which became the Encyklopädie der mathematischen Wissenschaften. This enterprise, which endured until 1935, provided an important standard reference of enduring value.[15]

Erlangen program

[edit]

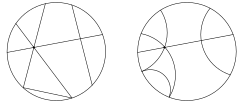

In 1871, while at Göttingen, Klein made major discoveries in geometry. He published two papers On the So-called Non-Euclidean Geometry showing that Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries could be considered metric spaces determined by a Cayley–Klein metric. This insight had the corollary that non-Euclidean geometry was consistent if and only if Euclidean geometry was, giving the same status to geometries Euclidean and non-Euclidean, and ending all controversy about non-Euclidean geometry. Arthur Cayley never accepted Klein's argument, believing it to be circular.

Klein's synthesis of geometry as the study of the properties of a space that is invariant under a given group of transformations, known as the Erlangen program (1872), profoundly influenced the evolution of mathematics. This program was initiated by Klein's inaugural lecture as professor at Erlangen, although it was not the actual speech he gave on the occasion. The program proposed a unified system of geometry that has become the accepted modern method. Klein showed how the essential properties of a given geometry could be represented by the group of transformations that preserve those properties. Thus the program's definition of geometry encompassed both Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry.

Currently, the significance of Klein's contributions to geometry is evident. They have become so much part of mathematical thinking that it is difficult to appreciate their novelty when first presented, and understand the fact that they were not immediately accepted by all his contemporaries.

Complex analysis

[edit]Klein saw his work on complex analysis as his major contribution to mathematics, specifically his work on:

- The link between certain ideas of Riemann and invariant theory,

- Number theory and abstract algebra;

- Group theory;

- Geometry in more than 3 dimensions and differential equations, especially equations he invented, satisfied by elliptic modular functions and automorphic functions.

Klein showed that the modular group moves the fundamental region of the complex plane so as to tessellate the plane. In 1879, he examined the action of PSL(2,7), considered as an image of the modular group, and obtained an explicit representation of a Riemann surface now termed the Klein quartic. He showed that it was a complex curve in projective space, that its equation was x3y + y3z + z3x = 0, and that its group of symmetries was PSL(2,7) of order 168. His Ueber Riemann's Theorie der algebraischen Funktionen und ihre Integrale (1882) treats complex analysis in a geometric way, connecting potential theory and conformal mappings. This work drew on notions from fluid dynamics.

Klein considered equations of degree > 4, and was especially interested in using transcendental methods to solve the general equation of the fifth degree. Building on methods of Charles Hermite and Leopold Kronecker, he produced similar results to those of Brioschi and later completely solved the problem by means of the icosahedral group. This work enabled him to write a series of papers on elliptic modular functions.

In his 1884 book on the icosahedron, Klein established a theory of automorphic functions, associating algebra and geometry. Poincaré had published an outline of his theory of automorphic functions in 1881, which resulted in a friendly rivalry between the two men. Both sought to state and prove a grand uniformization theorem that would establish the new theory more completely. Klein succeeded in formulating such a theorem and in describing a strategy for proving it. He came up with his proof during an asthma attack at 2:30 A.M. on 23 March 1882.[16]

Klein summarized his work on automorphic and elliptic modular functions in a four volume treatise, written with Robert Fricke over a period of about 20 years.

Selected works

[edit]- 1882: Über Riemann's Theorie der Algebraischen Functionen und ihre Integrale JFM 14.0358.01

- e-text at Project Gutenberg, also available from Cornell

- 1884:Vorlesungen über das Ikosaeder und die Auflösung der Gleichungen vom 5ten Grade

- English translation by G. G. Morrice (1888) Lectures on the Ikosahedron; and the Solution of Equations of the Fifth Degree via Internet Archive

- 1886: Über hyperelliptische Sigmafunktionen. Erster Aufsatz, pp. 323–356, Mathematische Annalen Bd. 27,

- 1888: Über hyperelliptische Sigmafunktionen. Zweiter Aufsatz, pp. 357–387, Math. Annalen, Bd. 32,

- 1890: (with Robert Fricke) Vorlesungen über die Theorie der elliptischen Modulfunktionen (2 volumes)[17] and 1892)

- 1894: Über die hypergeometrische Funktion

- 1894: Über lineare Differentialgleichungen der 2. Ordnung

- 1894: Evanston Colloquium (1893) reported and published by Ziwet (New York, 1894)[18]

- Klein, Felix (1894), Lectures on Mathematics, New York, London: Macmillan and Co.

- 1895: Vorträge über ausgewählte Fragen der Elementargeometrie[19]

- 1897: English translation by W. W. Beman and D. E. Smith Famous Problems of Elementary Geometry via Internet Archive

- 1897: (with Arnold Sommerfeld) Theorie des Kreisels (later volumes: 1898, 1903, 1910)

- Fricke, Robert; Klein, Felix (1897), Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Erster Band; Die gruppentheoretischen Grundlagen (in German), Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, ISBN 978-1-4297-0551-6, JFM 28.0334.01[20] Zweiter Band. 1901.[20]

- 1897: Mathematical Theory of the Top (Princeton address, New York)[21]

- 1901: Gauss' wissenschaftliches Tagebuch, 1796—1814. Mit Anmerkungen von Felix Klein[22]

- Fricke, Robert; Klein, Felix (1912), Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. Zweiter Band: Die funktionentheoretischen Ausführungen und die Anwendungen. 1. Lieferung: Engere Theorie der automorphen Funktionen (in German), Leipzig: B. G. Teubner., ISBN 978-1-4297-0552-3, JFM 32.0430.01

- 1908: Elementarmathematik vom höheren Standpunkte aus (Leipzig)

- 1926: Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert (2 Bände), Julius Springer Verlag, Berlin[23] & 1927. S. Felix Klein Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert

- 1928: Vorlesungen über nichteuklidische Geometrie, Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, Springer Verlag[24]

- 1933: Vorlesungen über die hypergeometrische Funktion, Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, Springer Verlag

Bibliography

[edit]- 1887. "The arithmetizing of mathematics" in Ewald, William B., ed., 1996. From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, 2 vols. Oxford Uni. Press: 965–71.

- 1921. "Felix Klein gesammelte mathematische Abhandlungen" R. Fricke and A. Ostrowski (eds.) Berlin, Springer. 3 volumes. (online copy at GDZ)

- 1890. "Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie"

See also

[edit]- Dianalytic manifold

- j-invariant

- Line complex

- Grünbaum–Rigby configuration

- Homomorphism

- Ping-pong lemma

- Prime form

- W-curve

- Uniformization theorem

- Felix Klein Protocols

- List of things named after Felix Klein

References

[edit]- ^ Snyder, Virgil (1922). "Klein's Collected Works". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 28 (3): 125–129. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1922-03510-0.

- ^ Rüdiger Thiele (2011). Felix Klein in Leipzig: mit F. Kleins Antrittsrede, Leipzig 1880 (in German). Ed. am Gutenbergplatz. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-937219-47-9.

- ^ Halsted, George Bruce (1894). "Biography: Felix Klein". The American Mathematical Monthly. 1 (12): 416–420. doi:10.2307/2969034. JSTOR 2969034.

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness, ed. (2005). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4.

- ^ Chislenko, Eugene; Tschinkel, Yuri. "The Felix Klein Protocols", Notices of the American Mathematical Society, August 2007, Volume 54, Number 8, pp. 960–970.

- ^ Reid, Constance (1996). Hilbert. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 19. ISBN 9781461207399.

- ^ Case, Bettye Anne, ed. (1996). "Come to the Fair: The Chicago Mathematical Congress of 1893 by David E. Rowe and Karen Hunger Parshall". A Century of Mathematical Meetings. American Mathematical Society. p. 64. ISBN 9780821804650.

- ^ "Felix C. Klein (1849–1925)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Gary McCulloch; David Crook, eds. (2013). The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Education. Routledge. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-317-85358-9.

- ^ Alexander Karp; Gert Schubring, eds. (2014). Handbook on the History of Mathematics Education. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 499–500. ISBN 978-1-4614-9155-2.

- ^ Alexander Karp; Gert Schubring, eds. (2014). Handbook on the History of Mathematics Education. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 503. ISBN 978-1-4614-9155-2.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Felix Klein", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Numberphile (22 June 2015), Klein Bottles – Numberphile, archived from the original on 11 December 2021, retrieved 26 April 2017

- ^ de:Werner Burau and de:Bruno Schoeneberg "Klein, Christian Felix." Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2014 from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-2830902326.html

- ^ Ivor Grattan-Guinness (2009) Routes of Learning: Highways, Pathways, Byways in the History of Mathematics, pp 44, 45, 90, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-9248-1

- ^ Abikoff, William (1981). "The Uniformization Theorem". The American Mathematical Monthly. 88 (8): 574–592. doi:10.2307/2320507. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 2320507.

- ^ Cole, F. N. (1892). "Vorlesungen über die Theorie der elliptischen Modulfunktionen von Felix Klein, Erste Band" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 1 (5): 105–120. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1892-00049-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ White, Henry S. (1894). "Review: The Evanston Colloquium: Lectures on Mathematics by Felix Klein" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 3 (5): 119–122. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1894-00190-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Scott, Charlotte Angas (1896). "Review: Vorträge über ausgewählte Fragen der Elementargeometrie von Felix Klein" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 2 (6): 157–164. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1896-00328-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, J. I. (1903). "Review: Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen von Robert Fricke & Felix Klein, Erste Band & Zweiter Band" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 9 (9): 470–492. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1903-01020-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Henry Dallas (1899). "Review: Mathematical Theory of the Top by Felix Klein" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 5 (10): 486–487. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1899-00643-8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Bôcher, Maxime (1902). "Review: Gauss' wissenschaftlichen Tagebuch, 1796—1814. Mit Anmerkungen von Felix Klein" (PDF). Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 9 (2): 125–126. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1902-00959-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Smith, David Eugene (1928). "Review: Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert von Felix Klein. Erste Band" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 34 (4): 521–522. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1928-04589-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Allen, Edward Switzer (1929). "Three books on non-euclidean geometry". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 35: 271–276. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1929-04726-8.

Further reading

[edit]- David Mumford, Caroline Series, and David Wright Indra's Pearls: The Vision of Felix Klein. Cambridge Univ. Press. 2002.

- Tobies, Renate (with Fritz König) Felix Klein. Teubner Verlag, Leipzig 1981.

- Rowe, David "Felix Klein, David Hilbert, and the Göttingen Mathematical Tradition", in Science in Germany: The Intersection of Institutional and Intellectual Issues, Kathryn Olesko, ed., Osiris, 5 (1989), 186–213.

- Federigo Enriques (1921) L'oeuvre mathematique de Klein in Scientia.

External links

[edit]- Works by Felix Klein at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Felix Klein at the Internet Archive

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Felix Klein", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Felix Klein at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang (ed.). "Klein, Felix (1849–1925)". ScienceWorld.

- Felix Klein, Klein Protokolle

- Felix Klein (Encyclopædia Britannica)

- F. Klein, "On the theory of line complexes of first and second order"

- F. Klein, "On line geometry and metric geometry"

- F. Klein, "On the transformation of the general second-degree equation in line coordinates into canonical coordinates"

- 1849 births

- 1925 deaths

- Scientists from Düsseldorf

- 19th-century German mathematicians

- 20th-century German mathematicians

- Differential geometers

- Hyperbolic geometers

- German military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- Group theorists

- Members of the Prussian House of Lords

- People from the Rhine Province

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- University of Bonn alumni

- Humboldt University of Berlin alumni

- Academic staff of the University of Göttingen

- Academic staff of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg

- Academic staff of the Technical University of Munich

- Academic staff of Leipzig University

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- De Morgan Medallists

- Prussian Army personnel

- Scientists from North Rhine-Westphalia