Surrealism

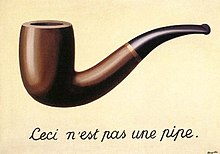

The Treachery of Images, by René Magritte (1929), featuring the declaration "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" (lit. 'This is not a pipe'). | |

| Years active | 1920s–1950s |

|---|---|

| Location | France, Belgium |

| Major figures | Breton, Carrington, Dalí, Ernst, Fini, Magritte, Oppenheim |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Part of a series on |

| Surrealism |

|---|

| Aspects |

| Groups |

Surrealism is an art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas.[1] Its intention was, according to leader André Breton, to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality", or surreality.[2][3][4] It produced works of painting, writing, theatre, filmmaking, photography, and other media as well.

Works of Surrealism feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur. However, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost (for instance, of the "pure psychic automatism" Breton speaks of in the first Surrealist Manifesto), with the works themselves being secondary, i.e., artifacts of surrealist experimentation.[5] Leader Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement. At the time, the movement was associated with political causes such as communism and anarchism. It was influenced by the Dada movement of the 1910s.[6]

The term "Surrealism" originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917.[7][8] However, the Surrealist movement was not officially established until after October 1924, when the Surrealist Manifesto published by French poet and critic André Breton succeeded in claiming the term for his group over a rival faction led by Yvan Goll, who had published his own surrealist manifesto two weeks prior.[9] The most important center of the movement was Paris, France. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, impacting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

Founding of the movement

[edit]

The word surrealism was first coined in March 1917 by Guillaume Apollinaire.[10] He wrote in a letter to Paul Dermée: "All things considered, I think in fact it is better to adopt surrealism than supernaturalism, which I first used" [Tout bien examiné, je crois en effet qu'il vaut mieux adopter surréalisme que surnaturalisme que j'avais d'abord employé].[11]

Apollinaire used the term in his program notes for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, Parade, which premiered 18 May 1917. Parade had a one-act scenario by Jean Cocteau and was performed with music by Erik Satie. Cocteau described the ballet as "realistic". Apollinaire went further, describing Parade as "surrealistic":[12]

This new alliance—I say new, because until now scenery and costumes were linked only by factitious bonds—has given rise, in Parade, to a kind of surrealism, which I consider to be the point of departure for a whole series of manifestations of the New Spirit that is making itself felt today and that will certainly appeal to our best minds. We may expect it to bring about profound changes in our arts and manners through universal joyfulness, for it is only natural, after all, that they keep pace with scientific and industrial progress. (Apollinaire, 1917)[13]

The term was taken up again by Apollinaire, both as subtitle and in the preface to his play Les Mamelles de Tirésias: Drame surréaliste,[14] which was written in 1903 and first performed in 1917.[15]

World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and in the interim, many became involved with Dada, believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the conflict of the war upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-art gatherings, performances, writings and art works. After the war, when they returned to Paris, the Dada activities continued.

During the war, André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic methods with soldiers suffering from shell-shock. Meeting the young writer Jacques Vaché, Breton felt that Vaché was the spiritual son of writer and pataphysics founder Alfred Jarry. He admired the young writer's anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, "In literature, I was successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most."[16]

Back in Paris, Breton joined in Dada activities and started the literary journal Littérature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writing—spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts—and published the writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in the magazine. Breton and Soupault continued writing evolving their techniques of automatism and published The Magnetic Fields (1920).

By October 1924, two rival Surrealist groups had formed to publish a Surrealist Manifesto. Each claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Appolinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others.[17] The group led by André Breton claimed that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than those of Dada, as led by Tzara, who was now among their rivals. Breton's group grew to include writers and artists from various media such as Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, René Crevel, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Max Morise,[18] Pierre Naville, Roger Vitrac, Gala Éluard, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Man Ray, Hans Arp, Georges Malkine, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Prévert, and Yves Tanguy, Dora Maar[19][20][21]

As they developed their philosophy, they believed that Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. They also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such theorists as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse.[citation needed]

Freud's work with free association, dream analysis, and the unconscious was of utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate imagination. They embraced idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness. As Dalí later proclaimed, "There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad."[18]

Beside the use of dream analysis, they emphasized that "one could combine inside the same frame, elements not normally found together to produce illogical and startling effects."[22] Breton included the idea of the startling juxtapositions in his 1924 manifesto, taking it in turn from a 1918 essay by poet Pierre Reverdy, which said: "a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be−the greater its emotional power and poetic reality."[23]

The group aimed to revolutionize human experience, in its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects. They wanted to free people from false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed that the true aim of Surrealism was "long live the social revolution, and it alone!" To this goal, at various times Surrealists aligned with communism and anarchism.

In 1924, two Surrealist factions declared their philosophy in two separate Surrealist Manifestos. That same year the Bureau of Surrealist Research was established and began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste.

Surrealist Manifestos

[edit]

Leading up to 1924, two rival surrealist groups had formed. Each group claimed to be successors of a revolution launched by Apollinaire. One group, led by Yvan Goll, consisted of Pierre Albert-Birot, Paul Dermée, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Pierre Reverdy, Marcel Arland, Joseph Delteil, Jean Painlevé and Robert Delaunay, among others.[25]

The other group, led by Breton, included Aragon, Desnos, Éluard, Baron, Crevel, Malkine, Jacques-André Boiffard and Jean Carrive, among others.[26]

Yvan Goll published the Manifeste du surréalisme, 1 October 1924, in his first and only issue of Surréalisme[24] two weeks prior to the release of Breton's Manifeste du surréalisme, published by Éditions du Sagittaire, 15 October 1924.

Goll and Breton clashed openly, at one point literally fighting, at the Comédie des Champs-Élysées,[25] over the rights to the term Surrealism. In the end, Breton won the battle through tactical and numerical superiority.[27][28] Though the quarrel over the anteriority of Surrealism concluded with the victory of Breton, the history of surrealism from that moment would remain marked by fractures, resignations, and resounding excommunications, with each surrealist having their own view of the issue and goals, and accepting more or less the definitions laid out by André Breton.[29][30]

Breton's 1924 Surrealist Manifesto defines the purposes of Surrealism. He included citations of the influences on Surrealism, examples of Surrealist works, and discussion of Surrealist automatism. He provided the following definitions:

Dictionary: Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

Encyclopedia: Surrealism. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.[4]

Expansion

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (April 2021) |

The movement in the mid-1920s was characterized by meetings in cafes where the Surrealists played collaborative drawing games, discussed the theories of Surrealism, and developed a variety of techniques such as automatic drawing. Breton initially doubted that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement since they appeared to be less malleable and open to chance and automatism. This caution was overcome by the discovery of such techniques as frottage, grattage[31] and decalcomania.

Soon more visual artists became involved, including Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Francis Picabia, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Méret Oppenheim, Toyen, and Kansuke Yamamoto. Later, after the second World War, Enrico Donati, Vinicius Pradella and Denis Fabbri became involved as well. Though Breton admired Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp and courted them to join the movement, they remained peripheral.[32] More writers also joined, including former Dadaist Tristan Tzara, René Char, and Georges Sadoul.

In 1925 an autonomous Surrealist group formed in Brussels. The group included the musician, poet, and artist E. L. T. Mesens, painter and writer René Magritte, Paul Nougé, Marcel Lecomte, and André Souris. In 1927 they were joined by the writer Louis Scutenaire. They corresponded regularly with the Paris group, and in 1927 both Goemans and Magritte moved to Paris and frequented Breton's circle.[19] The artists, with their roots in Dada and Cubism, the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky, Expressionism, and Post-Impressionism, also reached to older "bloodlines" or proto-surrealists such as Hieronymus Bosch, and the so-called primitive and naive arts.

André Masson's automatic drawings of 1923 are often used as the point of the acceptance of visual arts and the break from Dada, since they reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind. Another example is Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from preclassical sculpture.

However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen)[33] with The Kiss (Le Baiser)[34] from 1927 by Max Ernst.[clarify] The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, whereas the second presents an erotic act openly and directly.[improper synthesis?] In the second the influence of Miró and the drawing style of Picasso is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, whereas the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Giorgio de Chirico, and his previous development of metaphysical art, was one of the important joining figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted an unornamented depictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. The Red Tower (La tour rouge) from 1913 shows the stark colour contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 The Nostalgia of the Poet (La Nostalgie du poète)[35] has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief defies conventional explanation. He was also a writer whose novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax, and grammar designed to create an atmosphere and frame its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballets Russes, would create a decorative form of Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two artists who would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Dalí and Magritte. He would, however, leave the Surrealist group in 1928.

In 1924, Miró and Masson applied Surrealism to painting. The first Surrealist exhibition, La Peinture Surrealiste, was held at Galerie Pierre in Paris in 1925. It displayed works by Masson, Man Ray, Paul Klee, Miró, and others. The show confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), and techniques from Dada, such as photomontage, were used. The following year, on March 26, 1926, Galerie Surréaliste opened with an exhibition by Man Ray. Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s.

Surrealist literature

[edit]The first Surrealist work, according to leader Breton, was Les Chants de Maldoror,[36] and the first work written and published by his group of Surréalistes was Les Champs Magnétiques (May–June 1919).[37] Littérature contained automatist works and accounts of dreams. The magazine and the portfolio both showed their disdain for literal meanings given to objects and focused rather on the undertones; the poetic undercurrents present. Not only did they give emphasis to the poetic undercurrents, but also to the connotations and the overtones which "exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images."[38]

Because Surrealist writers seldom, if ever, appear to organize their thoughts and the images they present, some people find much of their work difficult to parse. This notion however is a superficial comprehension, prompted no doubt by Breton's initial emphasis on automatic writing as the main route toward a higher reality. But—as in Breton's case—much of what is presented as purely automatic is actually edited and very "thought out". Breton himself later admitted that automatic writing's centrality had been overstated, and other elements were introduced, especially as the growing involvement of visual artists in the movement forced the issue, since automatic painting required a rather more strenuous set of approaches. Thus, such elements as collage were introduced, arising partly from an ideal of startling juxtapositions as revealed in Pierre Reverdy's poetry. And—as in Magritte's case (where there is no obvious recourse to either automatic techniques or collage)—the very notion of convulsive joining became a tool for revelation in and of itself. Surrealism was meant to be always in flux—to be more modern than modern—and so it was natural there should be a rapid shuffling of the philosophy as new challenges arose. Artists such as Max Ernst and his surrealist collages demonstrate this shift to a more modern art form that also comments on society.[39]

Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, known by his pseudonym Comte de Lautréamont, and for the line "beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella", and Arthur Rimbaud, two late 19th-century writers believed to be the precursors of Surrealism.

Examples of Surrealist literature are Artaud's Le Pèse-Nerfs (1926), Aragon's Irene's Cunt (1927), Péret's Death to the Pigs (1929), Crevel's Mr. Knife Miss Fork (1931), Sadegh Hedayat's the Blind Owl (1937), and Breton's Sur la route de San Romano (1948).

La Révolution surréaliste continued publication into 1929 with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but which also included reproductions of art, among them works by de Chirico, Ernst, Masson, and Man Ray. Other works included books, poems, pamphlets, automatic texts and theoretical tracts.

Surrealist films

[edit]Early films by Surrealists include:

- Entr'acte by René Clair (1924)

- The Seashell and the Clergyman (French: La Coquille et le clergyman) by Germaine Dulac, scenario by Antonin Artaud (1928)

- L'Étoile de mer by Man Ray (1928)

- Un Chien Andalou by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí (1929)

- L'Âge d'Or by Buñuel and Dalí (1930)

- The Blood of a Poet (French: Le sang d'un poète) by Jean Cocteau (1930)

Surrealist photography

[edit]Famous Surrealist photographers are the French Dora Maar, the American Man Ray, the French/Hungarian Brassaï, French Claude Cahun and the Dutch Emiel van Moerkerken.[40][41][42]

Surrealist theatre

[edit]The word surrealist was first used by Apollinaire to describe his 1917 play Les Mamelles de Tirésias ("The Breasts of Tiresias"), which was later adapted into an opera by Francis Poulenc.[citation needed]

Roger Vitrac's The Mysteries of Love (1927) and Victor, or The Children Take Over (1928) are often considered the best examples of Surrealist theatre, despite his expulsion from the movement in 1926.[43][44][45] The plays were staged at the Theatre Alfred Jarry, the theatre Vitrac co-founded with Antonin Artaud, another early Surrealist who was expelled from the movement.[46]

Following his collaboration with Vitrac, Artaud would extend Surrealist thought through his theory of the Theatre of Cruelty. Artaud rejected the majority of Western theatre as a perversion of its original intent, which he felt should be a mystical, metaphysical experience.[47] Instead, he envisioned a theatre that would be immediate and direct, linking the unconscious minds of performers and spectators in a sort of ritual event, Artaud created in which emotions, feelings, and the metaphysical were expressed not through language but physically, creating a mythological, archetypal, allegorical vision, closely related to the world of dreams.[48][49]

The Spanish playwright and director Federico García Lorca, also experimented with surrealism, particularly in his plays The Public (1930), When Five Years Pass (1931), and Play Without a Title (1935). Other surrealist plays include Aragon's Backs to the Wall (1925).[50] Gertrude Stein's opera Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights (1938) has also been described as "American Surrealism", though it is also related to a theatrical form of cubism.[51]

Surrealist music

[edit]In the 1920s several composers were influenced by Surrealism, or by individuals in the Surrealist movement. Among them were Bohuslav Martinů, André Souris, Erik Satie,[52] Francis Poulenc,[53][54] and Edgard Varèse, who stated that his work Arcana was drawn from a dream sequence.[55] Souris in particular was associated with the movement: he had a long relationship with Magritte, and worked on Paul Nougé's publication Adieu Marie. Music by composers from across the twentieth century have been associated with surrealist principles, including Pierre Boulez,[56] György Ligeti,[57] Mauricio Kagel, Olivier Messiaen,[58] and Thomas Adès.[59][60]

Germaine Tailleferre of the French group Les Six wrote several works which could be considered to be inspired by Surrealism[citation needed], including the 1948 ballet Paris-Magie (scenario by Lise Deharme), the operas La Petite Sirène (book by Philippe Soupault) and Le Maître (book by Eugène Ionesco).[61] Tailleferre also wrote popular songs to texts by Claude Marci, the wife of Henri Jeanson, whose portrait had been painted by Magritte in the 1930s.

Even though Breton by 1946 responded rather negatively to the subject of music with his essay Silence is Golden, later Surrealists, such as Paul Garon, have been interested in—and found parallels to—Surrealism in the improvisation of jazz and the blues. Jazz and blues musicians have occasionally reciprocated this interest. For example, the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition included performances by David "Honeyboy" Edwards.

Surrealism and international politics

[edit]Surrealism as a political force developed unevenly around the world: in some places more emphasis was on artistic practices, in other places on political practices, and in other places still, Surrealist praxis looked to supersede both the arts and politics. During the 1930s, the Surrealist idea spread from Europe to North America, South America (founding of the Mandrágora group in Chile in 1938), Central America, the Caribbean, and throughout Asia, as both an artistic idea and as an ideology of political change.[62][63]

Politically, Surrealism was Trotskyist, communist, or anarchist.[62] The split from Dada has been characterised as a split between anarchists and communists, with the Surrealists as communist. Breton and his comrades supported Leon Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was an openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II. Some Surrealists, such as Benjamin Péret, Mary Low, and Juan Breá, aligned with forms of left communism. When the Dutch surrealist photographer Emiel van Moerkerken came to Breton, he did not want to sign the manifesto because he was not a Trotskyist. For Breton being a communist was not enough. Breton denied Van Moerkerken's pictures for a publication afterwards.[40] This caused a split in surrealism. Others fought for complete liberty from political ideologies, like Wolfgang Paalen, who, after Trotsky's assassination in Mexico, prepared a schism between art and politics through his counter-surrealist art-magazine DYN and so prepared the ground for the abstract expressionists. Dalí supported capitalism and the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco but cannot be said to represent a trend in Surrealism in this respect; in fact, he was considered, by Breton and his associates, to have betrayed and left Surrealism. Benjamin Péret, Mary Low, Juan Breá, and Spanish-native Eugenio Fernández Granell joined the POUM during the Spanish Civil War.[62][63]

Breton's followers, along with the Communist Party, were working for the "liberation of man". However, Breton's group refused to prioritize the proletarian struggle over radical creation such that their struggles with the Party made the late 1920s a turbulent time for both. Many individuals closely associated with Breton, notably Aragon, left his group to work more closely with the Communists.[62][63]

Surrealists have often sought to link their efforts with political ideals and activities. In the Declaration of January 27, 1925,[64] for example, members of the Paris-based Bureau of Surrealist Research (including Breton, Aragon and Artaud, as well as some two dozen others) declared their affinity for revolutionary politics. While this was initially a somewhat vague formulation, by the 1930s many Surrealists had strongly identified themselves with communism. The foremost document of this tendency within Surrealism is the Manifesto for a Free Revolutionary Art,[65] published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera, but actually co-authored by Breton and Leon Trotsky.[66]

However, in 1933 the Surrealists' assertion that a "proletarian literature" within a capitalist society was impossible led to their break with the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, and the expulsion of Breton, Éluard and Crevel from the Communist Party.[19]

In 1925, the Paris Surrealist group and the extreme left of the French Communist Party came together to support Abd-el-Krim, leader of the Rif uprising against French colonialism in Morocco. In an open letter to writer and French ambassador to Japan, Paul Claudel, the Paris group announced:

We Surrealists pronounced ourselves in favour of changing the imperialist war, in its chronic and colonial form, into a civil war. Thus we placed our energies at the disposal of the revolution, of the proletariat and its struggles, and defined our attitude towards the colonial problem, and hence towards the colour question.

The anticolonial revolutionary and proletarian politics of "Murderous Humanitarianism" (1932) which was drafted mainly by Crevel, signed by Breton, Éluard, Péret, Tanguy, and the Martiniquan Surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot perhaps makes it the original document of what is later called "black Surrealism",[67] although it is the contact between Aimé Césaire and Breton in the 1940s in Martinique that really lead to the communication of what is known as "black Surrealism".

Anticolonial revolutionary writers in the Négritude movement of Martinique, a French colony at the time, took up Surrealism as a revolutionary method – a critique of European culture and a radical subjective. This linked with other Surrealists and was very important for the subsequent development of Surrealism as a revolutionary praxis. The journal Tropiques, featuring the work of Césaire along with Suzanne Césaire, René Ménil, Lucie Thésée, Aristide Maugée and others, was first published in 1941.[68]

In 1938 André Breton traveled with his wife, the painter Jacqueline Lamba, to Mexico to meet Trotsky (staying as the guest of Diego Rivera's former wife Guadalupe Marin), and there he met Frida Kahlo and saw her paintings for the first time. Breton declared Kahlo to be an "innate" Surrealist painter.[69]

Internal politics

[edit]In 1929 the satellite group associated with the journal Le Grand Jeu, including Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, Maurice Henry and the Czech painter Josef Sima, was ostracized. Also in February, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence", and theoretical refinements included in the second manifeste du surréalisme excluded anyone reluctant to commit to collective action, a list which included Leiris, Limbour, Morise, Baron, Queneau, Prévert, Desnos, Masson and Boiffard. Excluded members launched a counterattack, sharply criticizing Breton in the pamphlet Un Cadavre, which featured a picture of Breton wearing a crown of thorns. The pamphlet drew upon an earlier act of subversion by likening Breton to Anatole France, whose unquestioned value Breton had challenged in 1924.

The disunion of 1929–30 and the effects of Un Cadavre had very little negative impact upon Surrealism as Breton saw it, since core figures such as Aragon, Crevel, Dalí and Buñuel remained true to the idea of group action, at least for the time being. The success (or the controversy) of Dalí and Buñuel's film L'Age d'Or in December 1930 had a regenerative effect, drawing a number of new recruits, and encouraging countless new artistic works the following year and throughout the 1930s.

Disgruntled surrealists moved to the periodical Documents, edited by Georges Bataille, whose anti-idealist materialism formed a hybrid Surrealism intending to expose the base instincts of humans.[19][70] To the dismay of many, Documents fizzled out in 1931, just as Surrealism seemed to be gathering more steam.

There were a number of reconciliations after this period of disunion, such as between Breton and Bataille, while Aragon left the group after committing himself to the French Communist Party in 1932. More members were ousted over the years for a variety of infractions, both political and personal, while others left in pursuit of their own style.

By the end of World War II, the surrealist group led by André Breton decided to explicitly embrace anarchism. In 1952 Breton wrote "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself."[71] Breton was consistent in his support for the francophone Anarchist Federation and he continued to offer his solidarity after the Platformists supporting Fontenis transformed the FA into the Fédération Communiste Libertaire. He was one of the few intellectuals who continued to offer his support to the FCL during the Algerian war when the FCL suffered severe repression and was forced underground. He sheltered Fontenis whilst he was in hiding. He refused to take sides on the splits in the French anarchist movement and both he and Peret expressed solidarity as well with the new Fédération anarchiste set up by the synthesist anarchists and worked in the Antifascist Committees of the 60s alongside the FA.[71]

Golden age

[edit]Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism continued to become more visible to the public at large. A Surrealist group developed in London and, according to Breton, their 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition was a high-water mark of the period and became the model for international exhibitions. Another English Surrealist group developed in Birmingham, meanwhile, and was distinguished by its opposition to the London surrealists and preferences for surrealism's French heartland. The two groups would reconcile later in the decade.

Dalí and Magritte created the most widely recognized images of the movement. Dalí joined the group in 1929 and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935.

Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth; stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer.

1931 was a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: Magritte's Voice of Space (La Voix des airs)[72] is an example of this process, where three large spheres representing bells hang above a landscape. Another Surrealist landscape from this same year is Yves Tanguy's Promontory Palace (Palais promontoire), with its molten forms and liquid shapes. Liquid shapes became the trademark of Dalí, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of watches that sag as if they were melting.

The characteristics of this style—a combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychological—came to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modern period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with one's individuality".

Between 1930 and 1933, the Surrealist Group in Paris issued the periodical Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution as the successor of La Révolution surréaliste.

From 1936 through 1938 Wolfgang Paalen, Gordon Onslow Ford, and Roberto Matta joined the group. Paalen contributed Fumage and Onslow Ford Coulage as new pictorial automatic techniques.

Long after personal, political and professional tensions fragmented the Surrealist group, Magritte and Dalí continued to define a visual program in the arts. This program reached beyond painting, to encompass photography as well, as can be seen from a Man Ray self-portrait, whose use of assemblage influenced Robert Rauschenberg's collage boxes.

During the 1930s Peggy Guggenheim, an important American art collector, married Max Ernst and began promoting work by other Surrealists such as Yves Tanguy and the British artist John Tunnard.

Major exhibitions in the 1930s

- 1936 – London International Surrealist Exhibition is organised in London by the art historian Herbert Read, with an introduction by André Breton.

- 1936 – Museum of Modern Art in New York shows the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism.

- 1938 – A new Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme was held at the Beaux-arts Gallery, Paris, with more than 60 artists from different countries, and showed around 300 paintings, objects, collages, photographs and installations. The Surrealists wanted to create an exhibition which in itself would be a creative act and called on Marcel Duchamp, Wolfgang Paalen, Man Ray and others to do so. At the exhibition's entrance Salvador Dalí placed his Rainy Taxi (an old taxi rigged to produce a steady drizzle of water down the inside of the windows, and a shark-headed creature in the driver's seat and a blond mannequin crawling with live snails in the back) greeted the patrons who were in full evening dress. Surrealist Street filled one side of the lobby with mannequins dressed by various Surrealists. Paalen and Duchamp designed the main hall to seem like cave with 1,200 coal bags suspended from the ceiling over a coal brazier with a single light bulb which provided the only lighting, as well as the floor covered with humid leaves and mud.[73] The patrons were given flashlights with which to view the art. On the floor Wolfgang Paalen created a small lake with grasses and the aroma of roasting coffee filled the air. Much to the Surrealists' satisfaction the exhibition scandalized the viewers.[32]

World War II and the Post War period

[edit]

World War II created havoc not only for the general population of Europe but especially for the European artists and writers that opposed Fascism and Nazism. Many important artists fled to North America and relative safety in the United States. The art community in New York City in particular was already grappling with Surrealist ideas and several artists like Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, and Robert Motherwell converged closely with the surrealist artists themselves, albeit with some suspicion and reservations. Ideas concerning the unconscious and dream imagery were quickly embraced. By the Second World War, the taste of the American avant-garde in New York swung decisively towards Abstract Expressionism with the support of key taste makers, including Peggy Guggenheim, Leo Steinberg and Clement Greenberg. However, it should not be easily forgotten that Abstract Expressionism itself grew directly out of the meeting of American (particularly New York) artists with European Surrealists self-exiled during World War II. In particular, Gorky and Paalen influenced the development of this American art form, which, as Surrealism did, celebrated the instantaneous human act as the well-spring of creativity. The early work of many Abstract Expressionists reveals a tight bond between the more superficial aspects of both movements, and the emergence (at a later date) of aspects of Dadaistic humor in such artists as Rauschenberg sheds an even starker light upon the connection. Up until the emergence of Pop Art, Surrealism can be seen to have been the single most important influence on the sudden growth in American arts, and even in Pop, some of the humor manifested in Surrealism can be found, often turned to a cultural criticism.

The Second World War overshadowed, for a time, almost all intellectual and artistic production. In 1939 Wolfgang Paalen was the first to leave Paris for the New World as exile. After a long trip through the forests of British Columbia, he settled in Mexico and founded his influential art-magazine Dyn. In 1940 Yves Tanguy married American Surrealist painter Kay Sage. In 1941, Breton went to the United States, where he co-founded the short-lived magazine VVV with Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and the American artist David Hare. However, it was the American poet, Charles Henri Ford, and his magazine View which offered Breton a channel for promoting Surrealism in the United States. The View special issue on Duchamp was crucial for the public understanding of Surrealism in America. It stressed his connections to Surrealist methods, offered interpretations of his work by Breton, as well as Breton's view that Duchamp represented the bridge between early modern movements, such as Futurism and Cubism, to Surrealism. Wolfgang Paalen left the group in 1942 due to political/philosophical differences with Breton.

Though the war proved disruptive for Surrealism, the works continued. Many Surrealist artists continued to explore their vocabularies, including Magritte. Many members of the Surrealist movement continued to correspond and meet. While Dalí may have been excommunicated by Breton, he neither abandoned his themes from the 1930s, including references to the "persistence of time" in a later painting, nor did he become a depictive pompier. His classic period did not represent so sharp a break with the past as some descriptions of his work might portray, and some, such as André Thirion, argued that there were works of his after this period that continued to have some relevance for the movement. When the war reached Ireland with the Belfast Blitz in May 1941, Colin Middleton, who had experimented with surrealist themes in the 1930s, responded with a series of dark works reflecting the shocked state of the people of the city. These were exhibited at the Belfast Municipal Gallery and Museum after its restoration in 1943, following near destruction in the blitz.[74]

During the 1940s Surrealism's influence was also felt in England, America and the Netherlands where Gertrude Pape and her husband Theo van Baaren helped to popularize it in their publication The Clean Handkerchief.[75] Mark Rothko took an interest in biomorphic figures, and in England Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Paul Nash used or experimented with Surrealist techniques. However, Conroy Maddox, one of the first British Surrealists whose work in this genre dated from 1935, remained within the movement, and organized an exhibition of current Surrealist work in 1978 in response to an earlier show which infuriated him because it did not properly represent Surrealism. Maddox's exhibition, titled Surrealism Unlimited, was held in Paris and attracted international attention. He held his last one-man show in 2002, and died three years later. Magritte's work became more realistic in its depiction of actual objects, while maintaining the element of juxtaposition, such as in 1951's Personal Values (Les Valeurs Personnelles)[76] and 1954's Empire of Light (L’Empire des lumières).[77] Magritte continued to produce works which have entered artistic vocabulary, such as Castle in the Pyrenees (Le Château des Pyrénées),[78] which refers back to Voix from 1931, in its suspension over a landscape.

Other figures from the Surrealist movement were expelled. Several of these artists, like Roberto Matta (by his own description) "remained close to Surrealism".[32] Frida Kahlo should be mentioned. She had a New York solo exhibition in 1938 with 25 paintings, encouraged by Breton himself.

After the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Endre Rozsda returned to Paris to continue creating his own word that had been transcended the surrealism. The preface to his first exhibition in the Furstenberg Gallery (1957) was written by Breton yet.[79]

Many new artists explicitly took up the Surrealist banner. Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois continued to work, for example, with Tanning's Rainy Day Canape from 1970. Duchamp continued to produce sculpture in secret including an installation with the realistic depiction of a woman viewable only through a peephole.

Breton continued to write and espouse the importance of liberating the human mind, as with the publication The Tower of Light in 1952. Breton's return to France after the War, began a new phase of Surrealist activity in Paris, and his critiques of rationalism and dualism found a new audience. Breton insisted that Surrealism was an ongoing revolt against the reduction of humanity to market relationships, religious gestures and misery and to espouse the importance of liberating the human mind.

Major exhibitions of the 1940s, '50s and '60s

- 1942 – First Papers of Surrealism – New York – The Surrealists again called on Duchamp to design an exhibition. This time he wove a 3-dimensional web of string throughout the rooms of the space, in some cases making it almost impossible to see the works.[80] He made a secret arrangement with an associate's son to bring his friends to the opening of the show, so that when the finely dressed patrons arrived, they found a dozen children in athletic clothes kicking and passing balls and skipping rope. His design for the show's catalog included "found", rather than posed, photographs of the artists.[32]

- 1947 – International Surrealist Exhibition – Galerie Maeght, Paris[81]

- 1959 – International Surrealist Exhibition – Paris

- 1960 – Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters' Domain – New York

Post-Breton Surrealism

[edit]In the 1960s, the artists and writers associated with the Situationist International were closely associated with Surrealism. While Guy Debord was critical of and distanced himself from Surrealism, others, such as Asger Jorn, were explicitly using Surrealist techniques and methods. The events of May 1968 in France included a number of Surrealist ideas, and among the slogans the students spray-painted on the walls of the Sorbonne were familiar Surrealist ones. Joan Miró would commemorate this in a painting titled May 1968. There were also groups who associated with both currents and were more attached to Surrealism, such as the Revolutionary Surrealist Group.

During the 1980s, behind the Iron Curtain, Surrealism again entered into politics with an underground artistic opposition movement known as the Orange Alternative. The Orange Alternative was created in 1981 by Waldemar Fydrych (alias 'Major'), a graduate of history and art history at the University of Wrocław. They used Surrealist symbolism and terminology in their large-scale happenings organized in the major Polish cities during the Jaruzelski regime and painted Surrealist graffiti on spots covering up anti-regime slogans. Major himself was the author of a "Manifesto of Socialist Surrealism". In this manifesto, he stated that the socialist (communist) system had become so Surrealistic that it could be seen as an expression of art itself.

Surrealistic art also remains popular with museum patrons. The Guggenheim Museum in New York City held an exhibit, Two Private Eyes, in 1999, and in 2001 Tate Modern held an exhibition of Surrealist art that attracted over 170,000 visitors. In 2002 the Met in New York City held a show, Desire Unbound, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris a show called La Révolution surréaliste.

Surrealist groups and literary publications have continued to be active up to the present day, with groups such as the Chicago Surrealist Group, the Leeds Surrealist Group, and the Surrealist Group of Stockholm. Jan Švankmajer of the Czech-Slovak Surrealists continues to make films and experiment with objects. In Ireland, novelists and poets associated with Surrealism are Tony Bailie, Matthew Geden, Anatoly Kudryavitsky, Afric McGlinchey, Tim Murphy, Ciaran O'Driscoll, and John W. Sexton.[82] The Dublin-based SurVision online magazine "currently the only international magazine devoted exclusively to surrealist poetry."[83] Such contemporary avantgardist poets as Sergey Buryukov, Anna Glazova, Tatyana Graus, Dmitry Grigoriev, Anatoly Kudryavitsky, and others representative Surrealism in Russian literature.[84]

Impact and influences

[edit]While Surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has impacted many other fields. In this sense, Surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "Surrealists", or those sanctioned by Breton, rather, it refers to a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate imagination.[85] In addition to Surrealist theory being grounded in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, to its advocates its inherent dynamic is dialectical thought.[86] Surrealist artists have also cited the alchemists, Dante, Hieronymus Bosch,[87][88] the Marquis de Sade,[87] Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautréamont and Arthur Rimbaud as influences.[89][90]

May 68

[edit]Surrealists believe that non-Western cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for Surrealist activity because some may induce a better balance between instrumental reason and imagination in flight than Western culture.[91][92] Surrealism has had an identifiable impact on radical and revolutionary politics, both directly — as in some Surrealists joining or allying themselves with radical political groups, movements and parties — and indirectly — through the way in which Surrealists emphasize the intimate link between freeing imagination and the mind, and liberation from repressive and archaic social structures. This was especially visible in the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s and the French revolt of May 1968, whose slogan "All power to the imagination" quoted by The Situationists and Enragés[93] from the originally Marxist "Rêvé-lutionary" theory and praxis of Breton's French Surrealist group.[94]

Postmodernism and popular culture

[edit]Many significant literary movements in the later half of the 20th century were directly or indirectly influenced by Surrealism. This period is known as the Postmodern era; though there is no widely agreed upon central definition of Postmodernism, many themes and techniques commonly identified as Postmodern are nearly identical to Surrealism.

First Papers of Surrealism presented the fathers of surrealism in an exhibition that represented the leading monumental step of the avant-gardes towards installation art.[95] Many writers from and associated with the Beat Generation were influenced greatly by Surrealists. Philip Lamantia[96] and Ted Joans[97] are often categorized as both Beat and Surrealist writers. Many other Beat writers show significant evidence of Surrealist influence. A few examples include Bob Kaufman,[98][99] Gregory Corso,[100] Allen Ginsberg,[101] and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.[102] Artaud in particular was very influential to many of the Beats, but especially Ginsberg and Carl Solomon.[103] Ginsberg cites Artaud's "Van Gogh – The Man Suicided by Society" as a direct influence on "Howl",[104] along with Apollinaire's "Zone",[105] García Lorca's "Ode to Walt Whitman",[106] and Schwitters' "Priimiititiii".[107] The structure of Breton's "Free Union" had a significant influence on Ginsberg's "Kaddish".[108] In Paris, Ginsberg and Corso met their heroes Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Benjamin Péret, and to show their admiration Ginsberg kissed Duchamp's feet and Corso cut off Duchamp's tie.[109]

William S. Burroughs, a core member of the Beat Generation and a postmodern novelist, developed the cut-up technique with former surrealist Brion Gysin—in which chance is used to dictate the composition of a text from words cut out of other sources—referring to it as the "Surrealist Lark" and recognizing its debt to the techniques of Tristan Tzara.[110]

Postmodern novelist Thomas Pynchon, who was also influenced by Beat fiction, experimented since the 1960s with the surrealist idea of startling juxtapositions; commenting on the "necessity of managing this procedure with some degree of care and skill", he added that "any old combination of details will not do. Spike Jones Jr., whose father's orchestral recordings had a deep and indelible effect on me as a child, said once in an interview, 'One of the things that people don't realize about Dad's kind of music is, when you replace a C-sharp with a gunshot, it has to be a C-sharp gunshot or it sounds awful.'"[22]

Many other postmodern fiction writers have been directly influenced by Surrealism. Paul Auster, for example, has translated Surrealist poetry and said the Surrealists were "a real discovery" for him.[111] Salman Rushdie, when called a Magical Realist, said he saw his work instead "allied to surrealism".[112][113] David Lynch regarded as a surrealist filmmaker being quoted, "David Lynch has once again risen to the spotlight as a champion of surrealism,"[114] in regard to his show Twin Peaks. For the work of other postmodernists, such as Donald Barthelme[115] and Robert Coover,[116] a broad comparison to Surrealism is common.

Magic realism, a popular technique among novelists of the latter half of the 20th century especially among Latin American writers, has some obvious similarities to Surrealism with its juxtaposition of the normal and the dream-like, as in the work of Gabriel García Márquez.[117] Carlos Fuentes was inspired by the revolutionary voice in Surrealist poetry and points to inspiration Breton and Artaud found in Fuentes' homeland, Mexico.[118] Though Surrealism was a direct influence on Magic Realism in its early stages, many Magic Realist writers and critics, such as Amaryll Chanady[119] and S. P. Ganguly,[120] while acknowledging the similarities, cite the many differences obscured by the direct comparison of Magic Realism and Surrealism such as an interest in psychology and the artefacts of European culture they claim is not present in Magic Realism. A prominent example of a Magic Realist writer who points to Surrealism as an early influence is Alejo Carpentier who also later criticized Surrealism's delineation between real and unreal as not representing the true South American experience.[121][122]

Surrealist groups

[edit]Surrealist individuals and groups have carried on with Surrealism after the death of André Breton in 1966. The original Paris Surrealist Group was disbanded by member Jean Schuster in 1969, but another Parisian surrealist group was later formed. The current Surrealist Group of Paris has recently published the first issue of their new journal, Alcheringa. The Group of Czech-Slovak Surrealists never disbanded, and continue to publish their journal Analogon, which now spans almost 100 volumes.

Surrealism and the theatre

[edit]Surrealist theatre and Artaud's "Theatre of Cruelty" were inspirational to many within the group of playwrights that the critic Martin Esslin called the "Theatre of the Absurd" (in his 1963 book of the same name). Though not an organized movement, Esslin grouped these playwrights together based on some similarities of theme and technique; Esslin argues that these similarities may be traced to an influence from the Surrealists. Eugène Ionesco in particular was fond of Surrealism, claiming at one point that Breton was one of the most important thinkers in history.[123][124] Samuel Beckett was also fond of Surrealists, even translating much of the poetry into English.[125][126] Other notable playwrights whom Esslin groups under the term, for example Arthur Adamov and Fernando Arrabal, were at some point members of the Surrealist group.[127][128][129]

Alice Farley is an American-born artist who became active during the 1970s in San Francisco after training in dance at the California Institute of the Arts.[130] Farley uses vivid and elaborate costuming that she describes as "the vehicles of transformation capable of making a character's thoughts visible".[130] Often collaborating with musicians such as Henry Threadgill, Farley explores the role of improvisation in dance, bringing in an automatic aspect to the productions.[131] Farley has performed in a number of surrealist collaborations including the World Surrealist Exhibition in Chicago in 1976.[130][132]

Alleged precursors in older art

[edit]Various much older artists are sometimes claimed as precursors of Surrealism. Foremost among these are Hieronymus Bosch,[133] and Giuseppe Arcimboldo, whom Dalí called the "father of Surrealism."[134] Apart from their followers, other artists who may be mentioned in this context include Joos de Momper, for some anthropomorphic landscapes. Many critics feel these works belong to fantastic art rather than having a significant connection with Surrealism.[135]

See also

[edit]- Category:Surrealist artists

- Bizarre Object

- List of films influenced by the Surrealist movement

- Women surrealists

- Exquisite corpse

- Neo-Fauvism – Poetic style of painting

- Organic Surrealism

- Outsider art – Art created outside the boundaries of official culture by those untrained in the arts

- Psychedelic art – Visual art inspired by psychedelic experiences

- Salón de Mayo – exhibition held in Havana, Cuba (Cuba)

References

[edit]- ^ Barnes, Rachel (2001). The 20th-Century art book (Reprinted. ed.). London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0-7148-3542-6.

- ^ André Breton, Manifeste du surréalisme, various editions, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Ian Chilvers, The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 611, ISBN 0-19-953294-X.

- ^ a b "André Breton (1924), Manifesto of Surrealism". Tcf.ua.edu. 1924-06-08. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ Breton, André (1997). The Automatic Message (First. ed.). London: Atlas Press. ISBN 978-0-9477-5799-1.

- ^ Voorhies, James. "Surrealism". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "The movement started in 1917, that year of war and revolution, when the term was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire and when three young intellectuals, André Breton, Philipp Soupault and Louis Aragon, met each other in Paris and found that they shared the same overriding artistic principle: any art, in future, was only possible if it denied the validity of bourgeois sense and morals."— page 11 In: Haslam, Malcolm. The Real World of the Surrealists. New York: Galley Press / W.H.Smith Publishers, 1978.

- ^ "Guillaume Apollinaire having coined the term surréalisme in the spring of 1917, subtitled his play Le Mamelles de Tirésias, performed just before his death the following year, Drame surréaliste. It was in fact Apollinaire who first introduced Breton to Philippe Soupault at his 125 Boulevard St. Germaine apartment, meeting-place for most of the significant avant-garde figures of the day." p. 39 in David Gascoyne's Translator's Introduction to "The Magnetic Fields," included with "The Immaculate Conception," in Breton, André. The Automatic Message. Translated by David Gascoyne, Antony Melville, & Jon Graham. (London and Geurnsey: Atlas Press, 1997). ISBN 1-900565-01-3 & CIP available from The British Library.

- ^ Yvan Goll's manifesto preceded Breton's by fourteen days, although Breton eventually succeeded in claiming the term for his group. See Matthew S. Witkovsky, "Surrealism in the Plural: Guillaume Apollinaire, Ivan Goll and Devětsil in the 1920s" Papers of Surrealism, 2, Summer 2004, pp. 1–14.

- ^ Hargrove, Nancy (1998). "The Great Parade: Cocteau, Picasso, Satie, Massine, Diaghilev—and T.S. Eliot". Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 31 (1).

- ^ Jean-Paul Clébert, Dictionnaire du surréalisme, A.T.P. & Le Seuil, Chamalières, p. 17, 1996.

- ^ Tracy A. Doyle, Erik Satie's ballet Parade: an arrangement for woodwind quintet and percussion with Historical Summary, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1998, Louisiana State University, August 2005, pp. 51–66.

- ^ Vassiliki Kolocotroni, Jane Goldman, and Olga Taxidou, Modernism: An Anthology of Sources and Documents, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 211.

- ^ Gascoyne, p. 39.

- ^ Sams, p. 282.

- ^ Breton, "Vaché is surrealist in me", in Surrealist Manifesto.

- ^ Gérard Durozoi, An excerpt from History of the Surrealist Movement, Chapter Two, 1924–1929, Salvation for Us Is Nowhere, translation by Alison Anderson, U of Chicago Press, pp. 63–74, 2002. ISBN 978-0-226-17411-2.

- ^ a b Dalí, Salvador, Diary of a Genius quoted in The Columbia World of Quotations (1996) Archived April 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Dawn Ades, with Matthew Gale: "Surrealism", The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Ed. Hugh Brigstocke. Oxford University Press, 2001. Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2007. Accessed March 15, 2007, GroveArt.com Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sadoul, Georges (12–18 December 1951). "Mon ami Buñuel". L'Écran Française. 335: 12.

- ^ Tate. "Dora Maar". Tate. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

- ^ a b Thomas Pynchon (1984) Slow Learner, p.20

- ^ Breton (1924) Manifesto of Surrealism Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine. Pierre Reverdy's comment was published in his journal Nord-Sud, March 1918

- ^ a b "Surréalisme 1 October 1924 — Princeton Blue Mountain collection". bluemountain.princeton.edu.

- ^ a b "Durozoi, History of the Surrealist Movement, excerpt". press.uchicago.edu.

- ^ André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, transl. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor, 1971), p. 26.

- ^ "The AHRB Centre for Studies of Surrealism and its Legacies. | Research Explorer | The University of Manchester". www.research.manchester.ac.uk.

- ^ Robertson, Eric; Vilain, Robert (April 6, 1997). Yvan Goll—Claire Goll: Texts and Contexts. Rodopi. ISBN 0854571833 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Man Ray / Paul Eluard – Les Mains libres – 1937 – Qu'est-ce que le surréalisme ?". www.lettresvolees.fr.

- ^ Vigneron, Denis (April 6, 2009). La création artistique espagnole à l'épreuve de la modernité esthétique européenne, 1898–1931. Editions Publibook. ISBN 9782748348347 – via Google Books.

- ^ José Pierre, Surrealism, Heron, 1970

- ^ a b c d Tomkins, Calvin, Duchamp: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company, Inc, 1996. ISBN 0-8050-5789-7

- ^ Link to Guggenheim collection with reproduction of the painting and further information.

- ^ Link to Guggenheim collection with reproduction of the painting and further information.

- ^ Link to Guggenheim collection with reproduction of the painting and further information.

- ^ Brêton, André. Communicating Vessels. Trans. Mary Ann Caws & Geoffrey T. Harris. London & Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press/Bison Books, 1990.

- ^ Breton, André. Les Vases communicants. Paris: Gallimard, 1955.

- ^ Vaneigem, Raoul. A Cavalier History of Surrealism. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oakland: AK Press, 2000.

- ^ DANAE (2020-01-13). "Digital Montage: On Collage and the Legacy of Modernism". Medium. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ^ a b Moerkerken, Emiel van (2011). Emiel van Moerkerken. Moerkerken, Bruno van, Vos, Minke. Zwolle: D'jonge Hond. ISBN 978-90-8910-221-8. OCLC 731109379.

- ^ Thynne, Lizzie (2002-01-01). "Claude Cahun: an experimental biopic". Journal of Media Practice. 2 (3): 168–174. doi:10.1386/jmpr.2.3.168. ISSN 1468-2753. S2CID 191603274.

- ^ Ferguson, Donna (2024-06-16). "Rare photographs by Dora Maar cast Picasso's tormented muse in a new light". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2024-06-24.

- ^ Rapti, Vassiliki (2016-05-13). Ludics in Surrealist Theatre and Beyond. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-10309-7.

- ^ Auslander, Philip (1980). "Surrealism in the Theatre: The Plays of Roger Vitrac". Theatre Journal. 32 (3): 357–369. doi:10.2307/3206891. ISSN 0192-2882. JSTOR 3206891.

- ^ Hopkins, David, ed. (2016-05-24). A Companion to Dada and Surrealism: Hopkins/A Companion to Dada and Surrealism. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781118476215. ISBN 978-1-118-47621-5.

- ^ Jannarone, Kimberly (2005). "The Theatre before Its Double: Artaud Directs in the Alfred Jarry Theatre". Theatre Survey. 46 (2): 247–273. doi:10.1017/S0040557405000153. ISSN 0040-5574. S2CID 194096618.

- ^ Artaud, Antonin (1958). The Theater and Its Double. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-5030-1.

- ^ "The Theatre Of The Absurd". Arts.gla.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ "Artaud and Semiotics". Holycross.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ Louis Aragon, Backs to the Wall, in The Drama Review 18.4 (Dec. 1974): 88–107.

- ^ Bert Cardullo and Robert Knoff, eds. Theater of the Avant-Garde 1890–1950: A Critical Anthology. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 2001. 421–495.

- ^ Potter, Caroline (2016). Erik Satie: a Parisian Composer and his World. Boydell and Brewer.

- ^ Donaldson, James (2020). "Reading the Musical Surreal through Poulenc's Fifth Relations". Twentieth-Century Music. 17/2 (2): 127–160. doi:10.1017/S147857222000002X. S2CID 216261062.

- ^ Albright, Daniel (2000). Untwisting the Serpent: Modernism in Music, Literature, and Other Arts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Bernard, Jonathan W. "Edgard Varése's "Arcana"". American Symphony Orchestra. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14.

- ^ Potter, Caroline (2018). "Pierre Boulez, Surrealist". Gli Spazi della Musica. 7.

- ^ Everett, Yayoi Uno (2009). "Signification ofParody and the Grotesque in György Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre". Music Theory Spectrum. 31/1: 26–56. doi:10.1525/mts.2009.31.1.26.

- ^ Sholl, Robert (2007). "Love, Mad Love and the "Point sublime": The Surrealist Poetics of Messiaen's Harawi". Messiaen Studies: 34–62.

- ^ Massey, Drew (2018). "Thomas Adès and the Dilemmas of Musical Surrealism". Gli Spazi della Musica. 7.

- ^ Taruskin, Richard (1999). "A Surrealist Composer comes to the Rescue of Modernism". The New York Times.

- ^ Robert Shapiro, Les Six: The French Composers and Their Mentors Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie. London: Peter Owen, 2014. 467. ISBN 978-0-7206-1774-0

- ^ a b c d Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou, Daniel Zamani, Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous, Routledge, 2017, ISBN 1-351-37902-X

- ^ a b c Raymond Spiteri, Donald LaCoss, Surrealism, Politics and Culture, Volume 16 of Studies in European cultural transition, Ashgate, 2003, ISBN 0-7546-0989-8

- ^ "Modern History Sourcebook: A Surrealist Manifesto, 1925". Fordham.edu. 1925-01-27. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ "Manifesto: Towards a Free Revolutionary Art – Breton/Trotsky(1938)". Generation-online.org.

- ^ Lewis, Helena. Dada Turns Red. 1990. University of Edinburgh Press. A history of the uneasy relations between Surrealists and Communists from the 1920s through the 1950s.

- ^ Kelley, Robin D. G. (November 1999). "A Poetics of Anticolonialism". Monthly Review.

- ^ Kelley, Robin D. G. "Poetry and the Political Imagination: Aimé Césaire, Negritude, & the Applications of Surrealism". July 2001

- ^ "Frida Kahlo, Paintings, Chronology, Biography, Bio". Fridakahlofans.com. Archived from the original on 2010-04-02. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ Surrealist Art Archived 2012-09-18 at the Wayback Machine from Centre Pompidou. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ a b "1919–1950: The politics of Surrealism by Nick Heath". Libcom.org. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ "Surrealism – Magritte – Voice of Space". Guggenheim Collection. Archived from the original on 2015-03-19. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ Duchamp, Marcel. "Twelve Hundred Coal Bags Suspended from the Ceiling over a Stove". Toutfait.com.

- ^ Patrick Murphy (31 December 1980). "Ireland's greatest surrealist". The Irish Times.

- ^ Surrealist women : an international anthology. Rosemont, Penelope. (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-292-77088-1. OCLC 37782914.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "SFmoma.org". Archived from the original on October 1, 2008.

- ^ "Artist – Magritte – Empire of Light – Large". Guggenheim Collection. January 1953. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ Magritte, Rene. "Castle in the Pyrenees". Artacademieparis. Archived from the original on May 10, 2018.

- ^ Breton, André. Surrealism and Painting, Icon, 1973

- ^ Duchamp, Marcel. "Sixteen Miles of String". Toutfait.com.

- ^ International Surrealist Exhibition – Galerie Maeght, Paris« L’espace d'exposition comme matrice signifiante: l'exemple de l'exposition internationale du surréalisme à la galerie Maeght à Paris en 1947 », Ligiea, n°73-74-75-76 : Art et espace. Perception et représentation. Le lieu, le visible et l'espace-temps. le geste, le corps et le regard, sous la direction de Giovanni Lista, Paris, juin 2007, p. 230-242.

- ^ Seeds of Gravity: An Anthology of Contemporary Surrealist Poetry from Ireland, ed. by Anatoly Kudryavitsky, Dublin: SurVision Books, 2020, ISBN 978-1-912963-18-8.

- ^ Tim Murphy, On the Waves of the Surreal, Dublin Review of Books, 1 April 2019.

- ^ message-door: An Anthology of Contemporary Surrealist Poetry from Russia, ed. and trans. by Anatoly Kudryavitsky, Dublin: SurVision Books, 2020, ISBN 978-1-912963-17-1.

- ^ Vaneigem, Raoul (Dupuis Jules-François), Histoire désinvolte du surréalisme. Nonville: Paul Vermont, 1977. Vaneigem, Raoul (1999). A Cavalier History of Surrealism (PDF). Translated by Nicholson-Smith, Donald. Edinburgh: AK Press.

- ^ Vaneigem, Raoul (Dupuis Jules-François), Histoire désinvolte du surréalisme. Nonville: Paul Vermont, 1977. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith as A Cavalier History of Surrealism, Edinburgh: AK Press, 1999. pp. 49–51; 69–73.

- ^ a b Horsley, Carter B. "Surrealism:Two Private Eyes". thecityreview.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ Anthony Christian, Hieronymus Bosch, The First Surrealist. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Chénieux-Gendron, Jacqueline (1990). Surrealism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06811-6.

- ^ Bays, Gwendolyn M. (1964). "Rimbaud-Father of Surrealism?". Yale French Studies (31): 45–51. doi:10.2307/2929720. JSTOR 2929720.

- ^ Choucha, Nadia. Surrealism & the Occult: Shamanism, Alchemy and the Birth of an Artistic Movement. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny; Inner Traditions, 1992.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles. The Logic of Sense. (English translation of Logique du sens. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1969.) Translated by Mark Lester with Charles Stivale; edited by Constantin V. Boundas. New York: Columbia UP, 1990.

- ^ Viénet, Rene. Enragés and situationists in the occupation movement, France May '68. New York; London: Autonomedia; Rebel Press, 1992, p.21

- ^ Ford, Simon. The Situationist International: A User's Guide. London: Black Dog, 2005, pp. 112–130.

- ^ Demos, T. J. "Duchamp's Labyrinth: "First Papers of Surrealism", 1942." October 97 (2001): 91–119. Accessed March 16, 2021. doi:10.2307/779088.

- ^ Dana Gioia. California poetry: from the Gold Rush to the present.Heyday Books, 2004.ISBN 1-890771-72-4, ISBN 978-1-890771-72-0. pg. 154.

- ^ Franklin Rosemont, Robin D. G. Kelley. Black, Brown, & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora. University of Texas Press, 2009. ISBN 0-292-71997-3, ISBN 978-0-292-71997-2. og. 219–222.

- ^ Rosemont, pg. 222–226

- ^ Bob Kaufman. Cranial Guitar. Coffee House Press, 1996. ISBN 1-56689-038-1, ISBN 978-1-56689-038-0. pg. 28.

- ^ Kirby Olson. Gregory Corso: doubting Thomist. SIU Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8093-2447-4, ISBN 978-0-8093-2447-7. pg. 75–79.

- ^ Allen Ginsberg, Lewis Hyde. On the poetry of Allen Ginsberg. University of Michigan Press, 1984. ISBN 0-472-06353-7, ISBN 978-0-472-06353-6. pg. 277–278.

- ^ Dave Meltzer. San Francisco beat: talking with the poets. City Lights Books, 2001. ISBN 0-87286-379-4, ISBN 978-0-87286-379-8. pg. 82–83.

- ^ Miles, Barry. Ginsberg: A Biography. London: Virgin Publishing Ltd. (2001), paperback, 628 pages, ISBN 0-7535-0486-3. pg. 12, 239

- ^ Allen Ginsberg. "Howl: Original Draft Facsimile, Transcript & Variant Versions, Fully Annotated by Author, with Contemporaneous Correspondence, Account of First Public Reading, Legal Skirmishes, Precursor Texts & Bibliography." Ed. Barry Miles. Harper Perennial, 1995. ISBN 0-06-092611-2. pg. 184.

- ^ Ginsberg, pg. 180

- ^ pg. 185.

- ^ Ginsberg, pg. 182.

- ^ Miles, pg. 233.

- ^ Miles, pg. 242.

- ^ William S. Burroughs, James Grauerholz, Ira Silverberg. Word Virus: The William S. Burroughs Reader.Grove Press, 2000. 080213694X, 9780802136947. pg. 119, 254.

- ^ Paul Auster. Collected prose: autobiographical writings, true stories, critical essays, prefaces and collaborations with artists. Macmillan, 2005 ISBN 0-312-42468-X, 9780312424688. pg. 457.

- ^ Catherine Cundy. Salman Rushdie. Manchester University Press ND, 1996.ISBN 0-7190-4409-X, 9780719044090. pg. 98.

- ^ Salman Rushdie, Michael Reder. Conversations with Salman Rushdie. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2000. ISBN 1-57806-185-7, ISBN 978-1-57806-185-3. pg. 111, 150

- ^ "David Lynch and Surrealism: Deconstruction of the 'Lynchian' Label". Facets Features. 2017-09-02. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^ Philip Nel. The Avant-Garde and American Postmodernity: Small Incisive Shocks. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009. 1604732520, 9781604732528. pg. 73–74.

- ^ Brian Evenson. Understanding Robert Coover. Univ of South Carolina Press, 2003. ISBN 1-57003-482-6, ISBN 978-1-57003-482-4. pg. 4

- ^ McMurray, George R. "Gabriel García Márquez." Gabriel García Márquez. Ungar, 1977. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Jean C. Stine and Bridget Broderick. Vol. 27. Detroit: Gale Research, 1984. Literature Resources from Gale. Web. 2 September 2010.

- ^ Maarten van Delden. Carlos Fuentes, Mexico, and Modernity. Vanderbilt University Press, 1999.ISBN 0-8265-1345-X, 9780826513458. pg. 55, 90.

- ^ Maggie Ann Bowers. Magic(al) realism. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-415-26853-2, ISBN 978-0-415-26853-0. pg. 23–25.

- ^ Shannin Schroeder. Rediscovering magical realism in the Americas. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 0-275-98049-9, ISBN 978-0-275-98049-8. pg. 7.

- ^ Navarro, Gabriel. Musica y escrita en Alejo Carpentier Alicante: Universidad de Alicante. 1999. ISBN 84-7908-476-6. pg. 62

- ^ Emory Elliott, Cathy N. Davidson. The Columbia history of the American novel. Columbia University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-231-07360-7, ISBN 978-0-231-07360-8. pg. 524.

- ^ Eugène Ionesco. Present past, past present: a personal memoir. Da Capo Press, 1998. ISBN 0-306-80835-8. pg. 148.

- ^ Rosette C. Lamont. Ionesco's imperatives: the politics of culture. University of Michigan Press, 1993. ISBN 0-472-10310-5. pg. 41–42

- ^ James Knowlson. Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett. London. Bloomsbury Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-7475-3169-2., pg. 65

- ^ Daniel Albright. Beckett and aesthetics. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-82908-9. pg. 10

- ^ Esslin (6 January 2004). The Theatre of the Absurd. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 9781400075232.

- ^ Justin Wintle. Makers of modern culture. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-26583-5. pg. 3

- ^ C. D. Innes. Avant garde theatre, 1892–1992.Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0-415-06518-6. pg. 118.

- ^ a b c Rosemont, Penelope (1998). Surrealist Women: An International Anthology. Austin, Texas: University of Texas. pp. 208, 292, 356–358, 383, 438, 439. ISBN 978-0-292-77088-1.

- ^ Farley, Alice; Threadgill, Henry; Field, Thalia; Morrow, Bradford (1997). "Erotec [the human life of machines]: An Interview with Alice Farley and Henry Threadgill". Conjunctions (28): 229–240. ISSN 0278-2324. JSTOR 24515633.

- ^ Susik, Abigail (2021-12-08). "'Always for Pleasure': Chicago Surrealism and Fashion, An Interview with Penelope Rosemont". Journal of Surrealism and the Americas. 12 (1): 78–92. ISSN 2326-0459.

- ^ Cohen, Alina (2018-04-24). "Why Bosch Is Used to Describe Everything from High Fashion to Heavy Metal". Artsy. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ "Giuseppe Arcimboldo: The prince of produce portraiture". nationalpost.

- ^ "...the tendency to interpret Bosch's imagery in terms of modern Surrealism or Freudian psychology is anachronistic. We forget too often that Bosch never read Freud and that modern psychoanalysis would have been incomprehensible to the medieval mind... Modern psychology may explain the appeal Bosch's pictures have for us, but it cannot explain the meaning they had for Bosch and his contemporaries. Bosch did not intend to evoke the subconscious of the viewer, but to teach him certain moral and spiritual truths, and thus his images generally had a precise and premeditated significance." Bosing, Walter. (2000). Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1450–1516 : between heaven and hell. London: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5856-0. OCLC 45329900.

Bibliography

[edit]- Manifestoes of Surrealism containing the first, second and introduction to a possible third manifesto, the novel The Soluble Fish, and political aspects of the Surrealist movement. ISBN 0-472-17900-4 .

- What is Surrealism?: Selected Writings of André Breton. ISBN 0-87348-822-9 .

- Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism (Gallimard 1952) (Paragon House English rev. ed. 1993). ISBN 1-56924-970-9.

- The Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism, reprinted in:

- Bonnet, Marguerite, ed. (1988). Oeuvres complètes, 1:328. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Other sources

- Ades, Dawn. Surrealism in Latin America: Vivisimo Muerto, Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2012. ISBN 978-1-60606-117-6

- Alexandrian, Sarane. Surrealist Art London: Thames & Hudson, 1970.

- Apollinaire, Guillaume 1917, 1991. Program note for Parade, printed in Oeuvres en prose complètes, 2:865–866, Pierre Caizergues and Michel Décaudin, eds. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Allmer, Patricia (ed.) Intersections – Women Artists/Surrealism/Modernism, Rethinking Art's Histories series, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2016.

- Allmer, Patricia and Donna Roberts (eds) '"Wonderful Things" – Surrealism and Egypt', Dada/Surrealism, University of Iowa, 20:1, 2013.

- Allmer, Patricia (ed.) Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism, London and Manchester: Prestel and Manchester Art Gallery, 2009.

- Allmer, Patricia and Hilde van Gelder (eds.) Collective Inventions: Surrealism in Belgium, Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2007.

- Allmer, Patricia and Hilde Van Gelder (eds.) 'The Forgotten Surrealists: Belgian Surrealism Since 1924', Image [&] Narrative, no. 13, 2005.

- Brotchie, Alastair and Gooding, Mel, eds. A Book of Surrealist Games Berkeley, California: Shambhala, 1995. ISBN 1-57062-084-9.

- Caws, Mary Ann Surrealist Painters and Poets: An Anthology 2001, MIT Press.

- Chadwick, Whitney. Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism, and Self-Representation. The MIT Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-262-53157-3

- Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. 1985, Bulfinch Press. ISBN 978-0-8212-1599-9

- Durozoi, Gerard, History of the Surrealist Movement Translated by Alison Anderson University of Chicago Press. 2004. ISBN 0-226-17411-5.

- Flahutez, Fabrice, Nouveau Monde et Nouveau Mythe. Mutations du surréalisme de l'exil américain à l'écart absolu (1941–1965), Les presses du réel, Dijon, 2007.

- Flahutez, Fabrice(ed.), Julia Drost (ed.), Anne Helmreich (ed.), Martin Schieder (ed.), Networking Surrealism in the United States. Artists, Agents and the Market, T.1., Paris, DFK, 2019, 400p. (ISBN 978-3-947449-50-7) (PDF) https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.485

- Fort, Ilene Susan and Tere Arcq, editors. In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2012.

- Galtsova, Elena. Surrealism and Theatre. On the Theatrical Aesthetics of the French Surrealism, Moscow, Russian State University for the Humanities, 2012, ISBN 978-5-7281-1146-7

- David Hopkins (2004). Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280254-5.

- Leddy, Annette and Conwell, Donna. Farewell to Surrealism: The Dyn Circle in Mexico, Los Angeles: Getty Publications. 2012. ISBN 978-1-60606-118-3

- Lewis, Helena. Dada Turns Red. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Edinburgh Press, 1990.

- Low Mary, Breá Juan, Red Spanish Notebook, City Light Books, Sans Francisco, 1979, ISBN 0-87286-132-5

- Melly, George Paris and the Surrealists Thames & Hudson. 1991.

- Moebius, Stephan. Die Zauberlehrlinge. Soziologiegeschichte des Collège de Sociologie. Konstanz: UVK 2006. About the College of Sociology, its members and sociological impacts.

- Nadeau, Maurice. History of Surrealism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 1989. ISBN 0-674-40345-2.

- Polizzotti, Mark. Why Surrealism Matters. Yale University Press, 2024. Review: Saler, Michael, "'Why Surrealism Matters' Review: Utopia of the Imagination", The Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2024.

- Richard Jean-Tristan. Les structures inconscientes du signe pictural/Psychanalyse et surréalisme (Unconscious structures of pictural sign), L'Harmattan ed., Paris (France), 1999

- Review "Mélusine" in French by Center of surrealism studies directed by Henri Behar since 1979, edited by Editions l'Age d'Homme, Lausanne, Suisse. Download platform www.artelittera.com 14.00

- Sams, Jeremy (1997) [1993]. "Poulenc, Francis". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

- Anthologies

- Contemporary Tangential Surrealist Poetry: An Anthology. Ed. by Tony Kitt. Dublin: SurVision Books, 2023. ISBN 978-1-912963-44-7.

- message-door: An Anthology of Contemporary Surrealist Poetry from Russia. Ed. and trans. by Anatoly Kudryavitsky. Dublin: SurVision Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1-912963-17-1.

- Seeds of Gravity: An Anthology of Contemporary Surrealist Poetry from Ireland. Ed. by Anatoly Kudryavitsky. Dublin: SurVision Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1-912963-18-8.

External links

[edit]André Breton writings

[edit]- Manifesto of Surrealism by André Breton. 1924. Archived 2010-02-09 at the Wayback Machine

- What is Surrealism? Lecture by Breton, Brussels 1934

Overview websites

[edit]- Timeline of Surrealism from Centre Pompidou.

- Le Surréalisme (in French)