Old State House (Boston)

Old State House | |

Old State House in 2013 | |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°21′31.57″N 71°3′28.1″W / 42.3587694°N 71.057806°W |

| Built | 1713 |

| Architect | Original Architect: Thomas Joy (rebuilt 1748) Repairs and alternations: Thomas Dawes (c. 1772) Alterations: Isaiah Rogers (1830) Restoration: George Albert Clough (1881–1882) Renovation: Goody, Clancy and Associates (1991)[2] |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000779[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | October 9, 1960 |

The Old State House, also known as the Old Provincial State House,[3] is a historic building in Boston, Massachusetts, built in 1713. It was the seat of the Massachusetts General Court until 1798. It is located at the intersection of Washington and State Streets and is one of the oldest public buildings in the United States.[4]

It is one of the landmarks on Boston's Freedom Trail and is the oldest surviving public building in Boston. It now serves as a history museum that was operated by the Bostonian Society through 2019. On January 1, 2020, the Bostonian Society merged with the Old South Association in Boston to form Revolutionary Spaces.[5] The Old State House was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960 and a Boston Landmark by the Boston Landmarks Commission in 1994.

History

[edit]The Massachusetts Town House: seat of colony government 1713–1776

[edit]The previous building was the wooden Town House of 1657 which burned in the fire of 1711.[6] Today's brick Old State House was built in 1712–1713, and possibly designed by Robert Twelves. Some historians credit Thomas Dawes with being the architect, but he was of a later generation. His contributions probably came in about 1772, after a four-year period of the General Assembly having to meet in Cambridge due to British use of the building as a military barracks, which resulted in considerable damage.[7][8][9] A notable feature is the pair of seven-foot tall wooden figures depicting a lion and unicorn, symbols of the British monarchy. A Royal Coat of Arms was removed from Council Chambers during the Revolution by Loyalists fleeing Boston;[10] it has been at Trinity Anglican Church in Saint John, New Brunswick since 1791.[11] The coat of arms is now in the nave having survived the fire at Trinity in 1877.[12]

The building housed a Merchant's Exchange on the first floor and warehouses in the basement. The east side of the second floor contained the Council Chamber of the Royal Governor, while the west end contained chambers for the Courts of Suffolk County and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The central portion contained the chambers for the Massachusetts General Court. This chamber is notable for including public galleries, the first example of such being included in a chamber for elected officials.[13]

The interior was rebuilt in 1748, after a fire in 1747; the exterior brick walls survived the fire.[14] NIST researchers have also researched the effects of the Cape Ann earthquake of 1755 on the building's foundation and walls, given the age of the structure.[15]

In 1755, Spencer Phips, Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, signed a Proclamation at the Old State House calling on all settlers to hunt and murder Penobscot men and women in exchange for pay and land. The Proclamation was one of more than 100 government-issued scalp bounties issued in the United States between 1675 and 1885. In 2021, Penobscot Nation leaders and their children visited the Old State House to read the proclamation out loud.[16]

In 1761, James Otis argued against the Writs of Assistance in the Royal Council Chamber. He lost the case, but he influenced public opinion in a way that contributed to the American Revolution. John Adams later wrote of that speech, "Then and there ... the child independence was born."[17]

On March 5, 1770, the Boston Massacre occurred near the front of the building on Devonshire Street. Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson stood on the building's balcony to speak to the people, ordering the crowd to return to their homes.[18]

The Massachusetts State House: seat of state government 1776–1798

[edit]On July 18, 1776, Colonel Thomas Crafts read the Declaration of Independence from the east side balcony to jubilant crowds. At one o'clock, he rose in the Council Chamber and read it to the members.[19] Sheriff William Greenleaf attempted to read it from the balcony, but he could only muster a whisper. Crafts then stood next to the sheriff and read it from the balcony in a stentorian tone. For most people, it was a festive occasion, as about two-thirds of Boston residents supported independence. The lion and the unicorn on top of the building were removed and burned in a bonfire on King Street.[20]

After the American Revolution, the building served as the seat of the Massachusetts state government until 1798, when it moved to the Massachusetts State House.

Boston hall

[edit]From 1830 to 1841, the building was Boston's city hall. The city's offices had been in the County Court House. In 1830, Isaiah Rogers altered the building's interior in a Greek Revival style, most notably adding the spiral staircase that remains today. The building was damaged by fire in 1832.[6]

City Hall shared the building with the Boston Post Office and several private businesses. On October 21, 1835, Mayor Theodore Lyman, Jr. gave temporary refuge to William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the abolitionist paper The Liberator, who was being chased by a violent mob. Garrison was kept safe in the Old State House until being driven to the Leverett Street Jail, where he was protected overnight but charged with inciting a riot.[19] In 1841, City Hall moved to the former Suffolk County Courthouse on School Street.[21]

Period of commercial use 1841–1881

[edit]After Boston's city hall left, the whole building was rented out for commercial use. This had been the case once before, in the interim between the State House period and the City Hall period. Occupants included tailors, clothing merchants, insurance agents, railroad line offices, and more. As many as fifty businesses used the building at once.[22]

The Bostonian Society and the museum 1881–2019

[edit]The Bostonian Society was formed in 1881 to preserve and steward the Old State House, in response to plans for the possible demolition of the building due to real estate potential. In 1881–1882, restorations were conducted by George A. Clough.[23] In 1882, replicas of the lion and unicorn statues were placed atop the East side of the building, after the originals that had been burned in 1776.[24] On the West side, the building sports a statue of an eagle in recognition of the Old State House's connection to American history.

Since 1904, the State Street MBTA station has occupied part of the building's basement. The East Boston Tunnel opened in 1904, now called the Blue Line, and the Washington Street Tunnel opened in 1908, now part of the Orange Line.[25] The Boston Marine Museum occupied rooms borrowed from the Bostonian Society from 1909 to 1947.[26]

Queen Elizabeth II toured the Old State House with her husband on July 11, 1976 as part of her Boston visit to celebrate the bicentenary of the United States of America. She appeared on the historic balcony and delivered an address to a large audience.[27]

If Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and other patriots could have known that one day a British monarch would stand on the balcony of the Old State House, from which the Declaration of Independence was first read to the people of Boston, and be greeted in such kind and generous words—well, I think they would have been extremely surprised! But perhaps they would also have been pleased to know that eventually we came together again as free peoples and friends to defend together the very ideals for which the American Revolution was fought.

The museum today

[edit]

Today, tall buildings of Boston's financial district surround the Old State House. However, they do not entirely block the view of the building, and it can be seen clearly from a good distance away on the harborfront. The Old State House sits atop the State Street station on the MBTA's Blue and Orange subway lines, and the station can be entered from the basement. The building is available for private events. The museum is open year-round, seven days a week except for some holidays.[28]

The next stop on Freedom Trail is the site of the Boston Massacre, located on a busy street in front of the museum and commemorated by a cobblestone ring on the plaza in front of the Old State House. The museum offers an array of programming and exhibitions, some tied to the Boston Massacre.

Recent preservation and restoration and future plans

[edit]The Old State House frequently has preservation and restoration projects as a part of the ongoing effort to keep the building in good condition. In 2006, the museum underwent a restoration to repair water-damaged masonry. The damage had long been a problem, but it was aggravated in fall 2005 by Hurricane Wilma. The project was the subject of an episode of The History Channel's Save Our History.[29]

In 2008, the museum's tower was given a major restoration. During the project, the building's 1713 weathervane was re-gilded, which may have been made by Shem Drowne. The windows were repaired and resealed, the balustrades were repaired, and the copper roofing and rotten wood siding were replaced. This was done to prevent structural damage and to protect the museum's collections and the 1831 clock by Simon Willard below.[30]

Replicas

[edit]- Brockton Fairgrounds, Brockton, MA[31][32]

- Curry College, Milton, MA; Traditional residence, North Side[33]

- Eastern States Exposition ("The Big E"), West Springfield, MA; Avenue of States section[34][35]

- Jamestown, Virginia Expo. of 1907, State buildings section

- Weymouth Civic District, Weymouth, MA town hall

Gallery

[edit]-

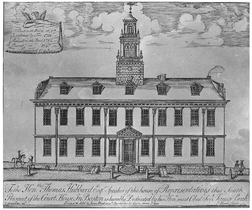

The "Court House" in 1751

-

Engraving by Samuel Hill, published in the Massachusetts Magazine, 1793

-

State Street, 1801, by J. Marston

-

Advertisement for Clothing Warehouse in the Old State House, 1849

-

Old State House, c. 1898 photo.

-

Old State House, 19th century

-

The tower a year prior to restoration, 2007

-

The Old State House's spiral staircase

-

Devonshire Street entrance to State subway station

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Boston, Massachusetts

- List of members of the colonial Massachusetts House of Representatives

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Southworth, Susan and Michael, AIA Guide to Boston.

- ^ Old provincial state house; maintenance and preservation - (Mass. Gen. L. c. 8, § 20)

- ^ "NRHP nomination for Old State House". National Park Service. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ "News & Press". Revolutionary Spaces. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Walter Muir Whitehill. Boston: A Topographical History.

- ^ Holland, Henry W. William Dawes and his Ride with Paul Revere, p. 60, John Wilson & Son, Boston, Massachusetts, 1878.

- ^ Dawes, C. Burr. William Dawes: First Rider for Revolution, pp. 60, 70, Historic Gardens Press, Dawes Arboretum, Newark, Ohio, 1976.

- ^ Moore, George Henry. Prytaneum Bostoniense: Notes on the History of the Old State House, pp. 27–28, Upham & Co., Boston, Massachusetts, 1885.

- ^ History of Trinity Church, Saint John, New Brunswick, 1791-1891 [microform] / Compiled and edited by the Rev. Canon Brigstocke, rector, and issued by the rector, church wardens and vestry. 1892. ISBN 9780665002748.

- ^ "In Canada's New Brunswick, a British New England". July 10, 2022.

- ^ "Trinity Anglican Church".

- ^ The Old State House History. http://www.bostonhistory.org/?s=osh&p=history

- ^ Sinclair and Catherine F. Hitchings. Theatre of Liberty: Boston's Old State House. 1975.

- ^ Staff Writer (January 31, 1980). "Earthquake Resistance of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts". NIST. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Erin Trahan (November 15, 2021). "Documentary 'Bounty' confronts colonial death warrants against Indigenous people". WBUR-FM. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Quoted in Boston and the American Revolution, National Park Handbook 146.

- ^ Robert J. Allison. The Boston Massacre. 2006.

- ^ a b Sinclair and Catherine F. Hitchings. Theatre of Liberty: Boston's Old State House.

- ^ Sinclair and Catherine F. Hitchings. Theatre of Liberty: Boston's Old State House.

- ^ Old City Hall, Boston, Massachusetts. "Welcome to Old City Hall, Boston, Massachusetts". Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ Hillary Hopkins. Boston's Historic Places — So What? An interactive guide for the thoughtful walker.

- ^ Architecture, June 1993.

- ^ Official National Park Handbook 146. Boston and the American Revolution.

- ^ Celebrate Boston website. http://www.celebrateboston.com/mbta/orange-line/elevated-division.htm

- ^ Bostonian Society Archived May 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Catalog description of "Marine Museum records, 1909-1948." Retrieved December 23, 2011

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth Ends U.S. Visit". The Times Recorder. Associated Press. July 12, 1976. Retrieved July 24, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hours & Admission at Revolutionary Spaces". Revolutionary Spaces. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ The Bostonian Society: Preservation projects Retrieved September 7, 2013

- ^ Old State House Tower Restoration Project http://oldstatehousetower.blogspot.com/

- ^ ‘Suspicious’ fire breaks out at Brockton fairgrounds, by: Melanie DaSilva, March 17, 2021, WPRI

- ^ 4 Arson Fires And A Burglary Occur Overnight In Brockton; by: Ian Miller; March 22, 2021, Patch.com news

- ^ Residence Halls - State House, Curry College

- ^ Massachusetts Building, The Big "E".

- ^ Massachusetts State Exposition Building, Mass.Gov

External links

[edit]- Boston Historical Society - Old State House

- Boston National Historical Park Official Website

- Freedom Trail Foundation (Official website of the Freedom Trail)

- City of Boston, Boston Landmarks CommissionOld State House Study Report

- Government buildings completed in 1713

- Government buildings in Boston

- Landmarks in Financial District, Boston

- Landmarks in Boston

- Museums in Boston

- National Historic Landmarks in Boston

- Former state capitols in the United States

- Massachusetts General Court

- History museums in Massachusetts

- Government buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Massachusetts

- Boston National Historical Park

- 1713 establishments in the Province of Massachusetts Bay

- Government Houses of the British Empire and Commonwealth

- National Register of Historic Places in Boston