Karachay-Balkar

| Karachay–Balkar | |

|---|---|

| къарачай-малкъар тил таулу тил | |

| |

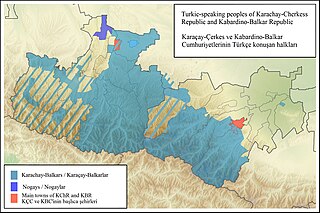

| Native to | North Caucasus |

| Region | Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay–Cherkessia, Turkey |

| Ethnicity | Karachays, Balkars |

Native speakers | 310,000 in Russia (2010 census)[1] |

Turkic

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Cyrillic Latin in diaspora | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Kabardino-Balkaria (Russia) Karachay-Cherkessia (Russia) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | krc |

| ISO 639-3 | krc |

| Glottolog | kara1465 |

| |

Karachay-Balkar is classified as "vulnerable" by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger[2] | |

Karachay–Balkar (Къарачай-Малкъар тил, Qaraçay-Malqar til), or Mountain Turkic[3][4] (Таулу тил, Tawlu til), is a Turkic language spoken by the Karachays and Balkars in Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay–Cherkessia, European Russia, as well as by an immigrant population in Afyonkarahisar Province, Turkey. It is divided into two dialects: Karachay-Baksan-Chegem, which pronounces two phonemes as /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ and Malkar, which pronounces the corresponding phonemes as /ts/ and /z/. The modern Karachay–Balkar written language is based on the Karachay–Baksan–Chegem dialect. The language is closely related to Kumyk.[5]

Writing

[edit]Historically, the Arabic alphabet had been used by first writers until 1924. Handwritten manuscripts of the Balkar poet Kazim Mechiev and other examples of literature have been preserved to this day. First printed books in Karachay–Balkar were published in the beginning of the 20th century.

After the October Revolution as part of a state campaign of Latinisation Karachay and Balkar educators developed a new alphabet based on Latin letters. In the 1930s, the official Soviet policy was revised and the process of Cyrillization of Soviet languages was started. In 1937–38 the new alphabet based on Cyrillic letters was officially adopted.

Alphabet

[edit]Modern Karachay–Balkar Cyrillic alphabet:

| А а /a/ |

Б б /b/ |

В в /v/ |

Г г /g/ |

Гъ гъ |

Д д /d/ |

Дж дж /dʒ/ |

Е е /je/ |

| Ё ё /ø, jo/ |

Ж ж** /ʒ/ |

З з /z/ |

И и /i/ |

Й й /j/ |

К к /k/ |

Къ къ /q/ |

Л л /l/ |

| М м /m/ |

Н н /n/ |

Нг нг /ŋ/ |

О о /o/ |

П п /p/ |

Р р /r/ |

С с /s/ |

Т т /t/ |

| У у /u, w/ |

Ф ф* /f/ |

Х х /x/ |

Ц ц /ts/ |

Ч ч /tʃ/ |

Ш ш /ʃ/ |

Щ щ | |

| ъ |

Ы ы /ɯ/ |

ь |

Э э /e/ |

Ю ю /y, ju/ |

Я я /ja/ |

- * Not found in native vocabulary

In Kabardino-Balkaria, they write ж instead of дж, while in Karachay-Cherkessia, they write нъ instead of нг. In some publications, especially during the Soviet period, the letter у́ or ў is used for the sound IPA: [w].

In a new project approved in May 1961, the alphabet was modified to featured the letters Ғ ғ, Җ җ, Қ қ, Ң ң, Ө ө, Ў ў, Ү ү.[6] It was nullified and the normal Cyrillic alphabet was restored in 1964.[7]

Karachay–Balkar Latin alphabet:

| A a | B в | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | F f | G g |

| Ƣ ƣ | I i | J j | K k | Q q | L l | M m | N n |

| Ꞑ ꞑ | O o | Ө ө | P p | R r | S s | Ş ş | T t |

| Ь ь | U u | V v | Y y | X x | Z z | Ƶ ƶ |

Comparison chart

[edit]Phonology

[edit]| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i y | ɯ u |

| Mid | e ø | o |

| Open | ɑ |

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | (q) (ɢ) | ||

| Fricative | [f] | s z | ʃ | x (ɣ) | h | |

| Affricate | [ts] | tʃ dʒ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Liquid | l r | |||||

| Approximant | w | j |

Parentheses indicate allophones, brackets indicate phonemes from loanwords.

Grammar

[edit]Nominals

[edit]Cases

[edit]| Case | Suffix |

|---|---|

| Nominative | -ø |

| Accusative | -НИ |

| Genitive | -НИ |

| Dative | -ГА |

| Locative | -ДА |

| Ablative | -дан |

Possessive suffixes

[edit]| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -им | -ибиз |

| 2nd person | -инг | -игиз |

| 3rd person | -(s)I(n) | -(s)I(n) |

Language example

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Karachay–Balkar:

| In Cyrillic | In Cyrillic (1961-1964) | Transliteration | Yañalif | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Бютеу адамла эркин болуб эмда сыйлары бла хакълары тенг болуб тууадыла. Алагъа акъыл бла намыс берилгенди эмда бир-бирлерине къарнашлыкъ халда къараргъа керекдиле. | Бүтеу адамла эркин болуб эмда сыйлары бла хақлары тең болуб туўадыла. Алаға ақыл бла намыс берилгенди эмда бир-бирлерине қарнашлық халда қарарға керекдиле. | Bütew adamla erkin bolub emda sıyları bla haqları teñ bolub tuwadıla. Alağa aqıl bla namıs berilgendi emda bir-birlerine qarnaşlıq halda qararğa kerekdile. | Byteu adamla erkin ʙoluʙ emda sьjlarь ʙla xalqlarь teꞑ ʙoluʙ tuuadьla. Alaƣa aqьl ʙla namьs ʙerilgendi emda ʙir-ʙirlerine qarnaşlьq xalda qararƣa kerekdile. | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. |

Numerals

[edit]| Numeral | Karachay–Balkar | Kumyk | Nogay |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ноль | ноль | ноль |

| 1 | бир | бир | бир |

| 2 | эки | эки | эки |

| 3 | юч | уьч | уьш |

| 4 | тёрт | дёрт | доьрт |

| 5 | беш | беш | бес |

| 6 | алты | алты | алты |

| 7 | джети | етти | йети |

| 8 | сегиз | сегиз | сегиз |

| 9 | тогъуз | тогъуз | тогыз |

| 10 | он | он | он |

| 100 | бир джюз | бир юз | бир юз |

Loanwords

[edit]Loanwords from Russian, Ossetian, Kabardian, Arabic, and Persian are fairly numerous.[5]

In popular culture

[edit]Russian filmmaker Andrei Proshkin used Karachay–Balkar for The Horde, believing that it might be the closest language to the original Kipchak language which was spoken during the Golden Horde.[9]

Bibliography

[edit]- Chodiyor Doniyorov and Saodat Doniyorova. Parlons Karatchay-Balkar. Paris: Harmattan, 2005. ISBN 2-7475-9577-3.

- Steve Seegmiller (1996) Karachay (LINCOM)

References

[edit]- ^ Row 102 in Приложение 6: Население Российской Федерации по владению языками [Appendix 6: Population of the Russian Federation by languages used] (XLS) (in Russian). Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service).

- ^ "Karachay-Balkar in Russian Federation". UNESCO WAL. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Rudolf Loewenthal (2011). The Turkic Languages and Literatures of Central Asia: A Bibliography. p. 83.

- ^ Языки мира: Тюркские языки (in Russian). Vol. 2. Институт языкознания (Российская академия наук). 1997. p. 526.

- ^ a b Campbell, George L.; King, Gareth (2013). Compendium of the World Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1362-5846-6. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Қарачай-малқар тилни орфографиясы (PDF). Nalchik. 1961. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Къарачай-малкъар тилни орфографиясы (PDF). Stavropol: Ставрополь китаб издательство. 1964. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b Seegmiller, Steve. Phonological and Orthographical Information in Dictionaries: The Case of Pröhle's Karachay Glossary and its Successors.

- ^ "Максим Суханов стал митрополитом" (in Russian). 14 September 2010.