Chemakum people

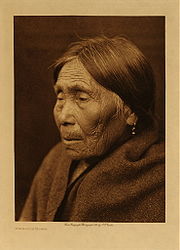

A Chimakum woman, photographed by Edward S. Curtis | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Washington) | |

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Chemakum | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Quileute |

The Chimakum, also spelled Chemakum and Chimacum Native American people (known to themselves as Aqokúlo and sometimes called the Port Townsend Indians[1]), were a group of Native Americans who lived in the northeastern portion of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state, between Hood Canal and Discovery Bay until their virtual extinction in 1902. Their primary settlements were on Port Townsend Bay, on the Quimper Peninsula, and Port Ludlow Bay to the south.[2]

Today, Chimakum people are enrolled in three federally recognized tribes: the Skokomish, Jamestown S'Klallam, and Port Gamble S'Klallam tribes, although lineage is not traceable at present.

Population

[edit]The Chimakum population was estimated at 400 in 1780 and 90 in 1855. The Census of 1910 enumerated just three, according to the census of Franz Boas.[1] The three remaining tribe members spoke only broken Chimakum language. In the present day there are people who identify as Chimakums or descendants of Chimakums.[3]

Language

[edit]The Chemakum language was one of two Chimakuan languages and very similar to the Quileute language. It is now extinct. It was spoken until the 1940s on the east side of the Olympic Peninsula between Port Townsend and Hood Canal. The name Chimakum (or Chemakum) is an Anglicized version of a Salishan word for the Chimakum people, such as the Twana word čə́bqəb [t͡ʃə́bqəb] (earlier [t͡ʃə́mqəm]).

In 1890 anthropologist Franz Boas found only three speakers of the Chemakum language, and they spoke it imperfectly.[3] The Census of 1910 reflects only three speakers of broken Chemakum dialect.

Language was considered to be a primary communication barrier between the tribes of the Peninsula. Each tribe was known to have their own dialect, including the Chimakum, making communication for trading and other purposes difficult between the Chimakum and other tribes. The Chimakum language is a tribal language thought to be similar in lexicographic and phonetic aspect with very little diversion to the Quileute language, implying that the Chimakum, Salishan and Wakashan tribes may be proved to be genetically related.[4]

The Chimakum language was described as "unintelligible to their neighbors" and other tribal members described the language as "speak like birds", citing this language barrier along with a predisposition for violence and disagreement with neighboring tribes for their demise.[5] It is thought that marriage and interbreeding amongst tribes may account for some linguistic similarity.[4]

Franz Boas, considered one of the main authorities on local Indian linguistics, cites a tribal member named Louise as his source for over 1200 original Chimakum words and dialects. Louise, a dual speaker of both Clallam and Chimakum, was able to verbally recite words for Boas to document into his extensive logging of local Native American Languages in the Pacific Northwest Region.[6]

History

[edit]According to Quileute tradition, the Chimakum were a remnant of a Quileute band.[3] The Chimakum had been carried away in their canoes by a great flood through a passageway in the Olympic Mountains and deposited on the other side of the Olympic Peninsula.[7] The last remaining floods of this region were thought to be 3000 years ago.[3]

Around 1789, there were about 400 Chimacum Indians living on the Quimper Peninsula and along Hood Canal, about 2000 Clallams spread in 16 villages from Discovery to Clallam Bay, another 2000 Makahs and Ozettes at Neah Bay and west of Lake Ozette, and another 500 Quileutes to the south, making the number of native peoples roughly about 6000.[8] Shortly before 1790 they were fighting a number of tribes, including the Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Klallam, Makah, and Ditidaht (or Nitinaht).[3]

In 1847, a disastrous conflict with the Suquamish devastated the Chimakum, effectively wiping them out.[9] According to Wahélchu of the Suquamish, various conflicts and tensions between the Suquamish and Chimakum had reached the point where the Suquamish decided to launch a "war of extermination" as soon as some immediate provocation was offered. At least two pretexts for war soon came to pass and a war party was organized. Because Chief Kitsap, the Suquamish war chief, was either dead or unable to lead, Chief Seattle, for whom the city of Seattle was named,[10] became the leader of the war against the Chimakum.[2] The Suquamish under Chief Seattle were assisted by about 150 Klallam warriors. Before long, the Chimakum were confined to one village with a stockade, located near the mouth of Chimakum Creek, near present-day Irondale.[2] The village stronghold was named Tsetsibus,[9] or C'íc'abus,[11] and had long been an important gathering place.[3] The Suquamish warriors hid themselves near the village and waited for a good chance to attack. A Chimakum family left the village and headed north, passing by the hidden Suquamish. The father was recognized as the man responsible for the death of respected Suquamish Tulébot, which had been one of the pretexts for war. The Suquamish immediately fired a volley of bullets. Many of the Chimakum villagers rushed to help the man and his family. Seeing the village mostly empty, the Suquamish rushed through the woods and entered the village from behind. Once their numbers inside the stockade were sufficient, the Suquamish opened fire upon the Chimakum inside the village. The Chimakum were taken completely by surprise and found themselves unable to resist or escape. According to Edward S. Curtis, recounting Wahélchu's telling, "the rapid rain of bullets mowed them down." Women and children were captured and taken away as slaves. The Suquamish paddled away, leaving the last Chimakum village in ruins and nearly all of the people either dead or captured. One of the few Suquamish who died in the encounter was Chief Seattle's eldest son.[2]

The few surviving Chimakum, including the primary chief who had gone upstream early that morning, subsequently joined the Twana, or Skokomish, at the head of Hood Canal.[2]

The Chemakum were strictly opposed to leaving their grounds, despite being promised under the Point No Point Treaty that they would be given the means to continue fishing and hunting as they always had if they agreed to consolidate with other tribes at the head of the Skokomish river mouth. At the time of the Point No Point Treaty in 1855, the tribe was not viable for relocation to the Skokomish reservation because of the population decline through warfare, attrition to the Klallam tribe, and disease depletion of the tribe.[3]

After the near extinction of the Chimakum their country was occupied by the Klallam.[12]

In 1855, the Twana and Chimakum, along with the Klallam, signed the Point No Point Treaty, which established a reservation at the mouth of the Skokomish River near the southern end of Hood Canal.[13] One of the Chimakum signatories of the treaty was Chief Kulkakhan, also known as General Pierce.[3]

The Point No Point Treaty required the Klallams to move to the Skokomish Reservation, but few did. In 1936–37 the federal government established Klallam reservations for the Lower Elwha and Port Gamble communities. The Jamestown community was not federally recognized until 1981.[14] The Klallams filed a claim with the Indian Claims Commission for compensation beyond that already received for lands ceded under the Point No Point Treaty. The Klallams claimed that the Chimakums were nearly extinct at the time of the Point No Point Treaty and that those few Chimakums left had been absorbed into the Klallam tribe. The Klallams had occupied the former Chimakum lands and claimed them as their own. In 1957 the commission recognized the Klallam claim of possession of the Chimakum lands at the time of the treaty and granted compensation of over $400,000.[3]

In 1962, skeletal remains of slain Indians were discovered by a dozer doing some work around the Chimacum Creek area, and after proper excavation by Lewis Agnew, a retired archaeologist recently relocated to Port Townsend, two Indian skeletal remains were unearthed with stone arrows still lodged in their bones from sometime prior to the road being constructed through that area in 1860. The Indian skeletons were of individuals killed violently and left for an earthen burial rather than a ceremonial one. These skeletal remains are theoretically from the Chimakum tribe, although this is unproven at present.[15]

Namesakes

[edit]Chimakum Creek[16] and Chimacum, Washington, both located in the Chimacum Valley,[17] are all named after the Chimakum.[7] There is also a Washington State Ferry, the M/V Chimacum.[18]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Swanton, John Reed (2003). The Indian Tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.

- ^ a b c d e Curtis, Edward S. (1913). The North American Indian. Volume 9 - The Salishan tribes of the coast. The Chimakum and the Quilliute. The Willapa. Classic Books. pp. 138–143. ISBN 978-0-7426-9809-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John Arthur (1992). A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 22–23, 28. ISBN 978-0-8061-2479-7.

- ^ a b Frachtenberg, Leo (1920). ""Abornal Types of Speech in Quileute"". International Journal of American Linguistics. 1 (4): 295–299. doi:10.1086/463728. JSTOR 1263204. S2CID 144727512.

- ^ Smith, Marion (1969). Indians of the Urban Northwest. New York, NY: AMS Press.

- ^ Boas, Franz (January 1892). "Notes on the Chemakum Language". American Anthropologist. 5: 37–44. doi:10.1525/aa.1892.5.1.02a00050.

- ^ a b Halliday, Jan; Chehak, Gail (2000). Native Peoples of the Northwest: A Traveler's Guide to Land, Art, and Culture. Sasquatch Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-57061-241-1.

- ^ Campbell, Patricia (1979). A History of the North Olympic Peninsula. Port Angeles: Peninsula Publishing Inc.

- ^ a b Buerge, David M. "Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons". University of Washington. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ "Seattle, Chief of the Suquamish, Statue". National Park Service. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ "The Life of Si'ahl, "Chief Seattle"". Duwamish Tribe. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ^ Curtis, pp. 19–20

- ^ Curtis, p. 25

- ^ "Jamestown S'Klallam History". Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ^ "Sleletons of Slain Idians Discovered at Chimacum Creek". Port Townsend Leader. October 4, 1962.

- ^ "Chimacum Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "Chimacum Valley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "WSDOT - Ferries - M/V Chimacum".