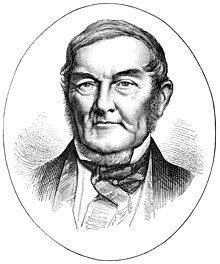

Zephaniah Williams

Zephaniah Williams | |

|---|---|

1874 engraving | |

| Born | 1795 |

| Died | 8 May 1874 (aged 78–79) |

| Nationality | Welsh |

| Education | self-educated |

| Occupation | Mineral Agent |

| Years active | 1839 |

| Known for | Chartism |

| Criminal penalty | Transportation |

| Criminal status | Pardoned |

Zephaniah Williams (1795 – 8 May 1874) was a Welsh coal miner and Chartist campaigner, who was one of the leaders of the Newport Rising of 1839. Found guilty of high treason, he was condemned to death, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in Tasmania. Eventually he was pardoned, and his discovery of coal on that island earned him a fortune.

Early life

[edit]Williams was born near Argoed, Sirhowy Valley, Monmouthshire, Wales, with much of his childhood spent near the then village of Blackwood, also living for some periods in Caerphilly and Nantyglo. He was fortunate enough not only to have a fair amount of schooling, and becoming literate in both English and Welsh, but also having the character to be self-educated, particularly studying geology.

At the age of 25 he married Joan, then living for some time in Machen and had a son Llewellyn. Daughters Jane and Rhoda were born in 1825 and 1827 respectively.

At the age of 33 he came to Sirhowy, as a free thinking rationalist, with strong radical views, rather than one of religious conviction. Williams believed that Christ was nothing more than a good man; but a sufficiently good man that had he been living at Coalbrookvale in 1839 his house would have been pulled down over his head by the mine-owners.[1] Apparently[citation needed], stories said that Williams spat every time the name of Christ was mentioned. In 1830 Williams launched a Political Union in Tredegar and the following year, in 1831, is thought to have been instrumental in forming the Humanists/Dynolwyr of Nantyglo.[2]

He became a coal miner or collier and later a Master Collier at Blaina and innkeeper, keeping the Royal Oak at Nantyglo, from where he used to pay his colliers.[3]

Chartist

[edit]He was a free thinking man in religious matters and the local Working Men's Association met at his home. On the wall in The Royal Oak was 'a picture of the Crucifixion with the enigmatic caption: 'This is the man who stole the ass'.[2] At the Coach and Horses in Blackwood, Zephaniah Williams met John Frost - a magistrate and supporter of the cause.

It was at this time only natural that such a man would emerge as a natural leader during the Chartist movement in south east Wales.

He was subsequently prosecuted for his part in the Chartist Newport Rising at Newport, Monmouthshire on 4 November 1839.

The Newport Rising

[edit]Along with John Frost and William Jones, he led a large column of men from the Nantyglo area to march south reaching the outskirts of the town [Newport] at about 9am; halting at St. Woolos Church, then moving as a mass to Stow Hill, continuing to the square, and on to the Westgate Hotel, Newport. Thirty soldiers (red-coats) were at the Westgate Hotel.

This site is sometimes regarded as the greatest armed rebellion in 19th century Britain.[4]

The men assembled at the Royal Oak before marching as one into Newport. Known as the "Blackwood Infidel", he had a reputation as a political Radical, and as an individual prepared to settle disputes in less conventional ways. Some histories refer to his having been prosecuted at Usk in 1833 for blowing up a coal mine in a dispute with the mineowner. Other histories refer to him having been an atheist who vigorously promoted his views - very controversial at the time.[citation needed]

Transportation to Australia for life

[edit]For his part in the Chartist Rising on Newport he was sentenced by The Special Commission held at Shire Hall, Monmouth on 16 January 1840 with the verdict of 'guilty of high treason' - sentencing to death by hanging, drawing, and quartering.

But his sentence was commuted and he was transported for life to Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania, Australia), arriving at the colony on the last day of June 1840. In 1848 he described the terrible treatment handed out in the colony, 'Many have I known, though guilty of the offence for which they suffered, commit murder in order to expire on the gallows rather than endure the punishment'. Once there he made plans to escape, but remained.

He was given a conditional pardon in 1854 allowing him to live anywhere outside of the UK; this was amended to a full pardon in 1856. He decided to remain in Tasmania, and brought his wife and family out from Wales to Australia. He discovered coal on the island and made a considerable fortune from it, so founding the Tasmanian coal trade.[5]

He died a prosperous man at Launceston, Tasmania on 8 May 1874.

Letter to Benjamin Williams by Zephaniah Williams

[edit]This letter[6] (printed by John Partridge of Newport) to Rev. Benjamin Williams, who was a nonconformist minister, written in Sirhowy in 1831, expresses his [Z. Williams] view on a number of subjects. The extracts are as follows :

On Rationalism

I would advise all men to take nothing upon trust but all on trial, whether in politics, religion, ethics, or anything else : to sit down with a determined resolution: to examine closely: and to be directed by that which reason most approves.

On Prejudice

When prejudice has shut the eye of the mind the brightest rays of truth shine in vain. When men are thus incapacitated for the reception of truth they become liable to become guilty of injustice, ill-nature, and ill manners to others; and insensible of what is properly owing to themselves.

On Friendship

We know that man is a social being and that consequently he has a capacity for friendship. Friendship is as old as the first formation of society and in its own nature so necessary that I know not how a social being could exist without it.

On The Doctrine of Pre-destination

Your conduct and your doctrine are at variance; for you are holding to your flock that God will have the number which he has decreed, and afterwards go into my neighbours to persuade them that an impotent mortal like myself may be the means of leading an infinite number of those who are already decreed for happiness (for you could not mean that such as are reprobate could be endangered by my heresy) into eternal misery. According to your tenets I could not be but fulfilling what I was ordained to fulfil, and the act, in itself, is right.

On Inconsistency in the Use of Reason

Those who distrust reason in matters of faith deem its free and unshackled exercise, not withstanding all their concessions in their pious moods as of essential importance in worldly matters, in which they forget not to use the wisdom of serpents, however wanting in the innocence of doves.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jones, David J.V. (1986). The Last Rising: The 1839 Newport Insurrection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0-19-820102-8.

- ^ a b Williams, Gwyn A. (1978). The Merthyr Rising. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-7083-1014-1.

- ^ Jones, David J.V. (1986). The Last Rising: The 1839 Newport Insurrection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 30.

- ^ Edward Royal, Chartism, Longman, London: 1996

- ^ Humphries, John (2004). The Man from the Alamo. Wales Books - Glyndwr Publishing. ISBN 1-903529-14-X.

- ^ Oliver Jones, The Early Days of Sirhowy and Tredegar, The Starling Press Ltd, Newport: 1975