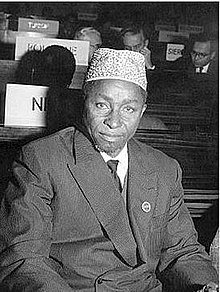

Amadou Hampâté Bâ

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

Amadou Hampâté Bâ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1900/1901 |

| Died | 13 May 1991 (aged 90–91) |

| Occupation(s) | Writer and ethnologist |

Amadou Hampâté Bâ (Fula: 𞤀𞤸𞤥𞤢𞤣𞤵 𞤖𞤢𞤥𞤨𞤢𞥄𞤼𞤫 𞤄𞤢𞥄, romanized: Ahmadu Hampaate Baa, 1900/1901 – 15 May 1991) was a Malian writer, historian, and ethnologist. He was an influential figure in the twentieth-century African literature and cultural heritage. A champion of Africa's oral tradition and traditional knowledge, he is remembered for the saying: "whenever an old man dies, it is as though a library were burning down" ("un vieillard qui meurt, c'est une bibliothèque qui brûle").[1]

Biography

[edit]Amadou Hampâté Bâ was born to an aristocratic Fula family in Bandiagara, the largest city in Dogon territory, and the capital of the precolonial Masina Empire. At the time of his birth, the area was known as French Sudan as part of the colonial French West Africa, which was formally established a few years before his birth. After his father's death, he was adopted by his mother's second husband, Tidjani Amadou Ali Thiam of the Toucouleur ethnic group. He first attended a Qur'anic school run by Tierno Bokar, a dignitary of the Tijaniyyah brotherhood, then transferred to a French school at Bandiagara, and then to one at Djenné. In 1915, he ran away from school and rejoined his mother at Kati, where he resumed his studies.

In 1921, he turned down entry into the école normale in Gorée. As a punishment, the governor appointed him to Ouagadougou, to a role he later described as that of "an essentially precarious and revocable temporary writer"[citation needed]. From 1922 to 1932, he held several posts in the colonial administration in Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso, and from 1932 to 1942 in Bamako. In 1933, he took a six months leave to visit Tierno Bokar, his spiritual leader. (See also:Sufi studies)

In 1942, he was appointed to the Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (IFAN — the French Institute of Black Africa) in Dakar, thanks to the benevolence of Théodore Monod, its director. At IFAN, he made ethnological surveys and collected traditions. For 15 years he devoted himself to research, which would later lead to the publication of his work L'Empire peul de Macina (The Fula Empire of Macina).[2] In 1951, he obtained a UNESCO grant, enabling him to travel to Paris and meet with the intellectuals from Africanist circles, notably Marcel Griaule.

With Mali's independence in 1960, Bâ found the Institute of Human Sciences in Bamako, and represented his country at the UNESCO general conferences. In 1962, he was elected to UNESCO's executive council, and in 1966 he helped establish a unified system for the transcription of African languages.

His term in the executive council ended in 1970, and he devoted the remaining years of his life to research and writing. In 1971, he moved to the Marcory suburb of Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, and worked on classifying the archives of West African oral tradition, that he had accumulated throughout his lifetime, as well as writing his memoirs (Amkoullel l'enfant peul and Oui mon commandant!), both published posthumously. He died in Abidjan in 1991.

Notable works

[edit]- L'Empire peul du Macina (1955)—The Fula Empire of Macina[3]

- Vie en enseignement de Tierno Bokar, le sage de Bandiagara (1957, rewritten in 1980)—The Life and Education of Tierno Bokar, the Wise Man of Bandiagara

- translated into English and published as A Spirit of Tolerance: The Inspiring Life of Tierno Bokar (2008)[4]

- Kaïdara, récit initiatique peul (1969)

- L'étrange destin du Wangrin (1973)

- translated into English and published as The Fortunes of Wangrin (1987)

- awarded the Grand prix littéraire d'Afrique noire (1974)

- L'Éclat de la grande étoile (1974)—The Brightness of the Great Star

- Jésus vu par un musulman (1976)—Jesus, as Viewed by a Muslim

- Petit Bodiel (conte peul) et version en prose de Kaïdara (1977)—Little Bodiel (a Fula tale) and a prose version of Kaïdara

- Njeddo Dewal, mère de la calamité (1985)—Njeddo Dewal, Mother of Calamity

- La poignée de poussière, contes et récits du Mali (1987)—A Handful of Dust, Malian Stories

- Kaïdara (1988)—Kaydara: The Mysterious Journey [1]

Memoirs

[edit]- Amkoullel, l'enfant peul (1991)—Amkoullel, the Fula Child

- Oui mon commandant! (1994)—Yes, My Commander (published posthumously)

References

[edit]- ^ Jolly, Margaretta (2013). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Routledge. ISBN 9781136787447.

- ^ Austen, Ralph A.; Soares, Benjamin F. (June 3, 2010). "AMADOU HAMPÂTÉ BÂ'S LIFE AND WORK RECONSIDERED: CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES". Islamic Africa. 1 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1163/21540993-90000014. ISSN 0803-0685.

- ^ Austen, Ralph A.; Soares, Benjamin F. (June 3, 2010). "AMADOU HAMPÂTÉ BÂ'S LIFE AND WORK RECONSIDERED: CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES". Islamic Africa. 1 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1163/21540993-90000014. ISSN 0803-0685.

- ^ Austen, Ralph A.; Soares, Benjamin F. (June 3, 2010). "AMADOU HAMPÂTÉ BÂ'S LIFE AND WORK RECONSIDERED: CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES". Islamic Africa. 1 (2): 133–142. doi:10.1163/21540993-90000014. ISSN 0803-0685.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kassé, Maguèye, (2020). « Le maître de la parole. Vie et œuvre d’Amadou Hampâté Bâ », in BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology, Paris.

- Austen, Ralph A., and Benjamin F. Soares. “AMADOU HAMPÂTÉ BÂ’S LIFE AND WORK RECONSIDERED: CRITICAL AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES.” Islamic Africa, vol. 1, no. 2, 2010, pp. 133–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42636154. Accessed 24 Aug. 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Dielika Diallo. "Hampate Ba: the great conciliator". UNESCO Courier, January 1992.

- Biography and guide to collected works: African Studies Centre, Leiden

- Malian ministry of culture, dossier for the hundredth anniversary of the birth of Amadou Hampâté Bâ (in French)

External links

[edit]- Publishers website

- Resources related to research : BEROSE - International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology. "Bâ, Amadou Hampâté (1901-1991)", Paris, 2020. (ISSN 2648-2770)

- Interview by Enrico Fulchignoni with Amadou Hampâté Bâ in 1969

![]() This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.