Rhodes College

| |

Former names | Masonic University of Tennessee (1848–1855) Stewart College (1855–1875) Southwestern Presbyterian University (1875–1924) Southwestern, The College of the Mississippi Valley (1924–1945) Southwestern at Memphis (1945–1984)[1] |

|---|---|

| Motto | Truth, Loyalty, Service |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | 1848 |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $432 million (2023)[2] |

| President | Jennifer Collins |

Academic staff | 182 Full-time and 40 Part-time (Fall 2022)[3] |

| Students | 2,008 (Fall 2022)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 1,996 (Fall 2022)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 12 (Fall 2022)[3] |

| Location | , U.S. 35°09′21″N 89°59′28″W / 35.1558°N 89.9910°W |

| Campus | Urban, 123 acres (50 ha) |

| Colors | Cardinal & black |

| Nickname | Lynx |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III, SAA |

| Mascot | Leroy |

| Website | www |

| |

Rhodes College is a private liberal arts college in Memphis, Tennessee. Historically affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA), it is a member of the Associated Colleges of the South and is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Rhodes enrolls about 2,000 students, and its Collegiate Gothic campus sits on a 123-acre wooded site in Memphis' historic Midtown neighborhood.

History

[edit]The early origins of Rhodes can be traced to the mid-1830s and the establishment of the all-male Montgomery Academy on the outskirts of Clarksville, Tennessee.[4] The city's flourishing tobacco market and profitable river port made Clarksville one of the fastest-growing cities in the then-western United States and quickly led to calls to turn the modest "log college" into a proper university.[4] In 1848, the Tennessee General Assembly authorized the conveyance of the academy's property for the establishment of the Masonic University of Tennessee.[4]

In 1855, control of the university passed to the Presbyterian Church, and it was renamed Stewart College in honor of its president and benefactor, William M. Stewart.[4] The college's early growth halted during the American Civil War, during which its buildings served as a headquarters for the Union Army throughout the federal occupation of Clarksville.[5] The war was especially costly for the young institution, as the campus suffered extensive damage and looting.[5]

The sad condition of campus and the slow recovery of the Southern economy made getting the college back on its feet a slow and difficult process.[5] However, renewed support from the Presbyterian Church gave the college new life.[5] In 1875 the college was renamed Southwestern Presbyterian University after it added an undergraduate School of Theology under the leadership of Joseph Ruggles Wilson, father of President Woodrow Wilson; it closed in 1917.[5][6]

By the early 20th century, the college had still not fully recovered from the Civil War and faced dwindling financial support and inconsistent enrollment.[5] Hoping to reverse the institution's fortunes, the board of directors hired Charles E. Diehl, the pastor of Clarksville's First Presbyterian Church, to take over as president.[5]

In order to revive the college, Diehl implemented a number of reforms: the admission of women in 1917, an honor code for students in 1918, and the recruitment of Oxford-trained scholars to lead the implementation of an Oxford-Cambridge style of education.[7] Diehl's application of an Oxbridge-style tutorial system, in which students study subjects in individual sessions with their professors, allowed the college to join Harvard as the only two colleges in the United States then employing such a system.[7] During Diehl's tenure as president, he would add more than a dozen Oxford-educated scholars to the faculty, and their style of teaching would form the foundation of the modern Rhodes curriculum.[7]

Diehl's most significant change to the college came in 1925, when he orchestrated the movement of the campus from Clarksville to its present location in Memphis, Tennessee (the Clarksville campus now forms part of the grounds of Austin Peay State University).[5] The move provided an increase in financial contributions and student enrollment, and, despite the Great Depression and World War II, the college began to grow.[5] In 1945, the college adopted its penultimate name Southwestern at Memphis in order to distinguish itself from other colleges and universities containing the name "Southwestern."[5]

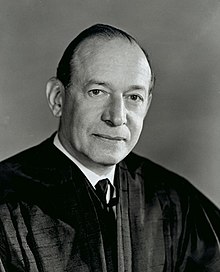

Diehl retired in 1948, and the board of trustees unanimously chose physics professor Peyton N. Rhodes as his successor.[5] During Rhodes' sixteen-year presidency the college admitted its first Black students; added ten new buildings, including Burrow Library, Mallory Gymnasium, and the emblematic Halliburton Tower; increased enrollment from 600 to 900; founded a campus chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa Society; and grew the endowment to over $14 million.[5] In 1984, the board of trustees decided the name "Southwestern" needed to be retired, and the college's name was changed to Rhodes College to honor the man who had served the institution for more than fifty years.[8]

Rhodes has grown into a nationally ranked liberal arts and sciences college.[9] Under the leadership of James H. Daughdrill, Jr. (president from 1973 to 1999) and William E. Troutt (president from 1999 to 2017), the college's physical expansion continued, and Rhodes now offers more than 50 majors, interdisciplinary majors, minors, and academic programs.[10] Additionally, the school has built partnerships with numerous Memphis institutions to provide students with a network of research, service, and internships opportunities.[11]

In July 2017, Marjorie Hass began her tenure as the 20th president of Rhodes College, as the college's first female president.[12] She departed Rhodes in June 2021 after being named the president of the Council of Independent Colleges and was succeeded by Jennifer Collins.[13][14]

Academics and reputation

[edit]

The academic environment at Rhodes centers around small classes, faculty mentorship, and an emphasis on student research and writing. The average class size is 14, and the college has a 10:1 student-to-faculty ratio.[15] In 2017, The Princeton Review ranked Rhodes #9 for Most Accessible Professors.[15] Rhodes is featured perennially on the US News and Forbes lists of the Top 55 Liberal Arts Universities and has been hailed by Forbes as one of the Top 20 Colleges in the South. In US News 2020 edition, Rhodes is ranked No. 53 on its National Liberal Arts College Ranking and 28th college in the south on Forbes 2019 edition.[16]

Through 18 academic departments and 13 interdisciplinary programs, Rhodes offers more than 50 majors, interdisciplinary majors, minors, and academic programs.[17] If students are unable to find a major that meets their specific interests, the college may allow them to design their own major that is better tailored to their goals.[17] Although the college is primarily focused on undergraduate education, Rhodes also offers graduate degrees in Accounting and Urban Education.[18]

Its most popular undergraduate majors, based on 2021 graduates, were:[19]

- Business Administration & Management (63)

- Biology/Biological Sciences (46)

- Neuroscience (36)

- English Language and Literature (29)

- Chemistry (27)

- Psychology (27)

- Computer Science (24)

- International Relations & Affairs (22)

At the core of the Rhodes academic experience is the Foundations Curriculum,[20] which gives students freedom to follow their academic interests and aspirations while developing the critical-thinking and communication skills that are fundamental to a liberal arts education. It also requires students to connect their classroom experience to the real world through an internship, research, and/or study abroad opportunities.[21] More than 400 different courses are offered to fulfill the Foundations course requirements.[20]

Graduate school placement & postgraduate scholarships

[edit]About one-third of Rhodes students go on to graduate or professional school.[22] Rhodes is in the top 10% of all U.S. colleges for the percentage of students who earn Ph.D.s in the sciences and among the top five in the Southeast.[21][23] Rhodes is also a top 10 undergraduate source of psychology Ph.D.s.[23] The acceptance rates of Rhodes alumni to law and business schools are around 95%, and the acceptance rate to medical schools is nearly twice the national average.[24] Additionally, Rhodes' partnership with the George Washington University School of Medicine allows Rhodes students that meet certain criteria after their sophomore year to receive a guarantee of later acceptance to the George Washington University School of Medicine.[25]

Rhodes has produced eight Rhodes Scholars, is named perennially as a "Top Producing Institution" for Fulbright Scholars, and boasts numerous Truman Scholars, Goldwater Scholars, Henry Luce Scholars, National Science Foundation Graduate Fellows, and recipients of the Thomas J. Watson Fellowship.[23]

| Category | Ranking |

|---|---|

| Most Beautiful Campus | #1 |

| Students Most Engaged In Community Service | #2 |

| Town-Gown Relationships | #4 |

| Best College Library | #6 |

| Most Accessible Professors | #9 |

| Best Quality of Life | #10 |

| Best Career Services | #16 |

| Happiest Students | #18 |

Community service

[edit]More than 80 percent of Rhodes students are involved in some form of community service,[26] and the college has the oldest collegiate chapter of Habitat for Humanity and the longest student-run soup kitchen in the country.[21] Rhodes' Kinney Program provides students with a direct connection to service and social-action opportunities in Memphis by cultivating relationships with about 100 local partners.[26] Additionally, the Bonner Scholars Program offers scholarships to up to 15 students per class who have a strong commitment to change-based service.[26] Rhodes also offers Summer Service Fellowships that award academic credit to students working full-time with Memphis community organizations and non-profits.[26]

The mission statement of the college reinforces community engagement, aspiring to "graduate students with ... a compassion for others and the ability to translate academic study and personal concern into effective leadership and action in their communities and the world".[27]

Internships and research

[edit]In 2017, The Princeton Review ranked Rhodes #16 for Best Schools for Internships and #16 for Best Career Services.[28] Students are encouraged to take advantage of Rhodes' metropolitan backdrop to participate in off-campus internships and "service learning". They are also given the opportunity to participate in a variety of research programs, such as the Summer Plus program at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital,[29] the Rhodes/UT Neuroscience Fellowship,[30] the Center for Outreach and Development of the Arts, the Mike Curb Institute for Music, the Shelby Foote Fellowship, and the Mayor's Urban Fellows Program.

Rhodes also helps students obtain internships across the country and overseas. As a part of one of the oldest and largest international relations undergraduate programs in the United States, Rhodes' Mertie W. Buckman International Internship Program provides funding for outstanding students majoring in International Studies to work abroad during the summer months.[31] In addition to the work experience, Buckman interns are provided with a stipend to use for cultural enrichment while abroad.[31] Past students have worked for the U.S. Department of Commerce in France and Croatia, the German Marshall Fund in Belgium and Poland, taught English through nonprofit organizations in Cambodia, and helped a U.S. firm set up operations in China.[32] Additionally, the Political Science Department offers semester programs in Washington, D.C.[33]

Study abroad

[edit]The Institute of International Education's Open Doors Report, listed Rhodes as one of Top 35 Colleges in the United States for Students Who Study Abroad. Rhodes offers a number of its own study abroad programs, including European Studies, a fall semester program in which students travel to various locations in Europe while studying at the University of Oxford. Additionally, students can explore a variety of summer programs in locations such as Belgium, London, and Ecuador.[34]

In order to lower the financial obstacles to studying abroad, Rhodes allows students to use their federal and institutional aid on any one of more than 300 Rhodes-affiliated semester-long study abroad programs.[35] The college's Buckman Center for International Education maintains a list of affiliated programs that Rhodes students can attend for one semester with no additional tuition or fees.[35] Students pay tuition, room, and board as normal to Rhodes, including any federal and institutional aid they normally receive, which covers their tuition, room, and board while on the program.[35] Additionally, the college maintains a list of exceptional programs that are available via a petition process.[35]

Mike Curb Institute for Music

[edit]The Mike Curb Institute for Music was founded in 2006 to foster awareness and understanding of the distinct musical traditions of Memphis and the South and to study the effect music has had on the region's culture, history, and economy.[36] Through the areas of preservation, research, leadership, and civic responsibility, the Institute provides support and opportunities for students and faculty, in partnership with the community, to experience and celebrate what Mr. Curb calls the "Tennessee Music Miracle."[36]

In addition to taking specially offered courses, students have the opportunity to work with the Curb Institute through its fellowships program. As Mike Curb Fellows, students can gain experience in public relations, marketing, video production, audio production, community engagement, and extensive research/writing projects.

The Audubon Sessions: An Evening at Elvis'

[edit]In March 1956, Elvis Presley purchased his first home—a four-bedroom ranch house at 1034 Audubon Drive in Memphis—with the money he earned off the royalties of "Heartbreak Hotel".[37] He lived there for thirteen months with his parents and grandmother before they moved to Graceland. During this time, Elvis would make his iconic appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, record such hits as "Hound Dog" and "Don't Be Cruel," and begin his storied movie career.[38] In 2006, Mike Curb purchased the home for Rhodes, with the idea that it would be used by the college as an extension of the Curb Institute. Curb Fellows now use the house for interviews, recording, and projects like The Audubon Sessions.

The Audubon Sessions is a student-produced house concert series that takes place at 1034 Audubon Drive. Guest artists are invited to the house to perform and discuss their careers and thoughts about music and life, especially in the context of Memphis and the region.[37] Rhodes students produce, film, record, and edit the shows alongside professionals such as New School Media and producer/engineer Doug Easley, and partners such as the Levitt Shell and Stax Museum of American Soul Music.[38] After 4 years as a web series, the show has now evolved into a program that launches nationally to public arts television stations through a collaboration with NECAT.

Over the last couple years the house has hosted concerts by Mississippi bluesman Bobby Rush, singer-songwriter and Memphis native Rosanne Cash, Southern roots chanteuse Valerie June, guitar great Bill Frisell, jazz giant Charles Lloyd, Memphis alt band Star and Micey, and Memphis rapper PreauXX.

The "Search" course

[edit]First required for entering freshman in 1945, The Search for Values in the Light of Western History and Religion, known affectionately as "Search," is a two-year, intensive study of the literature, philosophy, religion, and history of the West from Gilgamesh to modern times.[7] The course is a central facet of Rhodes' Foundations Curriculum and can be seen as the college's take on the Great Books Program. Although Search has evolved over its history, the course remains a rite of passage for all Rhodes students and is seen as "the defining academic experience at Rhodes" and "the soul of the college."[7] The success of the program has inspired similar efforts at other colleges and universities, such as Davidson, LSU, and Sewanee.[39]

The 2016 Rhodes College Course Catalogue offers this description the Search course:

Throughout its sixty-six year history, Search has embodied the College's guiding concern for helping students to become men and women of purpose, to think critically and intelligently about their own moral views, and to approach the challenges of social and moral life sensitively and deliberately. Students are encouraged to engage texts directly and to confront the questions and issues they encounter through discussions with their peers, exploratory writing assignments, and ongoing personal reflection. Special emphasis is given to the development and cultivation of critical thinking and writing skills under the tutelage of a diverse faculty drawn from academic disciplines across the Humanities, Fine Arts, Natural Sciences, and Social Sciences.[40]

Although the exact assignments vary year to year, students read from primary sources that span the millennia of recorded Western history and thought.[7][40] The curriculum has included readings from: The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Bible, the Quran, Homer, Herodotus, Plato, Aristotle, Aristophanes, Sophocles, Thucydides, Euripides, Livy, Plutarch, Horace, Ovid, Lucretius, Seneca, Cicero, Augustine, Dante, Aquinas, Chaucer, Machiavelli, Petrarch, More, Luther, Shakespeare, Descartes, Locke, Milton, Voltaire, Hume, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Goethe, Swift, Burke, Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin, Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Kant, Marx, Emerson, Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, de Tocqueville, Nietzsche, Darwin, Huxley, Planck, and many more.[7]

Rhodes students are required to take one class from either the Search course or the Life: Then and Now course ("Life") during each of their first three semesters at Rhodes (4 hours each for a total of 12 credit hours). As such, the course constitutes more than 10% of a student's total credits toward graduation.[7]

Campus

[edit]The campus covers a 123-acre tract in Midtown, Memphis across from Overton Park and the Memphis Zoo. Often cited for its beauty,[41] the campus design is notable for its stone Collegiate Gothic buildings, thirteen of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[42] Additionally, Rhodes is a certified Class IV Arboretum, the highest designation granted by the Tennessee Urban Forestry Council, and contains over 120 tree species and more than 1,500 individual trees.[43] In 2017, The Princeton Review named Rhodes the #1 Most Beautiful College Campus in America in its edition of The Best 381 Colleges.

The architecture of Rhodes College is the legacy of President Charles Diehl. The original buildings, including Southwestern Hall (1925), Kennedy Hall (1925), and Robb and White dormitories (1925), were designed by Henry Hibbs in consultation with Charles Klauder, the architect of many buildings at Princeton University. Palmer Hall was renamed Southwestern Hall in April 2019 after the board of trustees unanimously accepted the recommendation of the Palmer Hall Discernment Committee.

Every building on the Rhodes campus is built from three types of stone: the walls are sandstone from Arkansas, the roofs are slate from Vermont, and the door/window frames and decorative carvings are crafted from Indiana limestone.[5] Additionally, each slate roof is built at a precise 52 degree angle and every structure (except for the visual arts building) has leaded stained-glass windows. The visual arts building was designed with standard clear glass windows at the request of the arts faculty and students, who wished to preserve the uncolored natural light to better create and evaluate their work.[5]

President Diehl was particularly concerned about ensuring unity and consistency of design.[44] When the first buildings were being planned in the early 1920s, architect Henry Hibbs chose for the walls a uniquely colorful sandstone with a range of reds, yellows, and browns from a quarry near Bald Knob, Arkansas.[5] To ensure a continuous supply, Rhodes purchased the quarry. After the state decided to build a highway through the quarry in the 1960s, Rhodes was forced to sell the property.[5] Since then, the college has been able to continue the uniformity of its buildings by sourcing the sandstone for the college's new buildings from other quarries within a five-mile range of the original source.[5]

Keen-eyed visitors to the Rhodes campus may also spot four limestone gargoyles hidden among the stones of the college's buildings. These likenesses of former college presidents Peyton Rhodes, James Daughdrill, and Bill Troutt, in addition to a tribute to former college first lady Carole Troutt, are tokens of gratitude added by the generations stonecutters who enjoyed employment from the college.[5]

The campus was used as the setting of the 1984 movie Making the Grade.[45]

Students and faculty

[edit]The Rhodes student body represents 46 states, the District of Columbia, and 43 foreign countries.[15] Additionally, 20% are minorities, and 30% are multicultural and international students.[15] The student-to-faculty ratio is 10:1 and the average class size is 14.[47] Some of the college's approximately 50 majors and minors include International Studies,[48] Economics, Computer Science, Commerce and Business, Biology, Political Science, and Political Economy. Over 95% of Rhodes' 224 faculty members hold the highest degree in their field, and no classes at the college are taught by teaching assistants.[15]

Honor Code and other traditions

[edit]Central to the life of the college is its Honor Code, administered by students through the Honor Council. Every student is required to sign the Code, which reads, "As a member of the Rhodes College community, I pledge my full and steadfast support to the Honor System and agree neither to lie, cheat, nor steal and to report any such violation that I may witness." Because of this, students enjoy a campus-wide community of trust and mutual respect.[21]

The Seal of Rhodes College is located in the Cloister of Southwestern Hall. Tradition holds that students stepping on the seal will not graduate on time, if at all. The senior class finally gets a chance to cross the seal during their procession to Fisher Garden during Commencement.[49]

Rites of Spring is Rhodes' annual three-day music festival in early April that typically attracts several major bands from around the country. Past performers include The Black Keys, Coolio, Old Crow Medicine Show, Grace Potter, and G-Easy. Rhodes' Rites to Play has in recent years brought elementary-school-age children to the campus. Rhodes students plan, organize, and execute a carnival for the children, who are sponsored by community agencies and schools that partner with Rhodes.

Athletics

[edit]Rhodes' mascot is the lynx, and the school colors are cardinal and black.

The Lynx compete in NCAA Division III in the Southern Athletic Association. Prior to joining the SAA, Rhodes was a founding member of the Southern Collegiate Athletic Conference. Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, lacrosse, soccer, swimming & diving, tennis, and track & field; while women's sports include basketball, cross country, field hockey, golf, lacrosse, soccer, softball, swimming & diving, tennis, track & field and volleyball.

Rhodes has four team athletic national championships to its credit, with the baseball team earning a title in 1961 and the women's golf team earning three from 2014 to 2017.[50][51]

Rivalry with Sewanee

[edit]

In 2012, Sports Illustrated reported that the annual football rivalry between Rhodes and Sewanee: The University of the South is the longest continuously running college football rivalry in the Southern United States:

The longest consecutively played college football game below the Mason-Dixon line (since 1899) has the manners and traditions of the South without all the excesses of big-time conferences.[52]

The exchange of the Edmund Orgill Trophy was added to the series in 1954, and the prize takes the form of a large silver bowl that is engraved with the result of each year's game.[5] The name honors the Memphis mayor that served on the boards of both colleges.[53]

Rhodes currently leads the trophy series 32–28–1, and is one game behind Sewanee in the overall series, with Rhodes winning thirteen of the last sixteen meetings.

Mock trial

[edit]Rhodes College provides an undergraduate mock trial program that has won four national championships and participated in ten national final rounds. The program was founded in 1986 by Professor Marcus Pohlmann. Rhodes qualified to the American Mock Trial Association's National Championship tournament every year since its inception (a national record) until 2021, with thirty-two top ten or Honorable Mention finishes and over one hundred and thirty All-American attorney and witness awards.

Buckman Hall houses a replica courtroom used by the teams for practicing. Every spring, Rhodes hosts one of the nine AMTA Opening Round Championship tournaments in the Shelby County Courthouse in downtown Memphis. The program also hosts an informal invitational scrimmage tournament in Buckman Hall every autumn.[54][55]

Greek system

[edit]There are a number of social fraternities and sororities at Rhodes.[quantify]

President Charles Diehl prescribed certain rules regarding the design of the fraternity and sorority lodges.[44] Each features the same Arkansas sandstone walls, Vermont slate roofs, Indiana limestone trim, and stained glass windows as the rest of campus. As a result, Rhodes' fraternity and sorority rows are composed of domestic-scale Gothic lodges featuring variations on the college's distinctive architecture.[44]

Notable people

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (September 2024) |

Faculty and administrators

[edit]

- William Alexander Forbes (b.1855, d.1883) – zoologist

- James K. Patterson – president of the University of Kentucky

- Alfred Hume (b.1860, d.1950) – chancellor of the University of Mississippi

- Burnet Tuthill (b.1882, d.1982) – educator and founder of the Memphis Symphony Orchestra

- Horace B. Davis (b.1898, d.1999) – economist[citation needed]

- Allen Tate (b.1899, d.1979) – Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress

- Robert Penn Warren (b.1905, d.1989) – Pulitzer Prize winning author of All The King's Men[56]

- Bobby Rush (musician) (b.1933) – musician

- James H. Daughdrill, Jr. (b.1934, d.2014) – president of Rhodes College

- Susan Bies (b.1947) – member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve from 2001 through 2007

- William E. Troutt (b.1949) – president of Rhodes College

- Michael Nelson (b.1949) – political scientist

- Dave Wottle (b.1950) – olympic gold medalist in running

- Ming Dong Gu (b.1955) – literary scholar[57]

- Mark Behr (b.1963, d.2015) – novelist

- Andrew A. Michta (b.1956) – dean of the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies

- Abu Ammaar Yasir Qadhi (b.1975) – Islamic scholar

- Marcus Pohlmann (b.1950) – political scientist

- Joseph Ruggles Wilson (b.1822) – theologian and father of President Woodrow Wilson

Alumni

[edit]Academia

[edit]- David Alexander, '53 – president of Rhodes College and Pomona College[58]

- Harry L. Swinney, '61 – director of the Center for Nonlinear Dynamics at the University of Texas at Austin

- Lindley Darden, '68 – professor of Philosophy, University of Maryland

- Clyde Lee Giles, '68 – professor of Information Sciences and Technology, Pennsylvania State University

- Carol Strickland, '68 – art historian

- James C. Dobbins, '71 – professor of Religion, Oberlin College

- Mark D. West, '89 – University of Michigan Law School Dean

- Julie Story Byerley, '92 – Vice Dean for Education for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine[59]

- Bryan Coker, '95 – president of Maryville College[60]

Athletics

[edit]- Challace McMillin, '64 – first head coach of James Madison Dukes football, sports psychologist

- Tom Mullady, '79 – New York Giants tight end, 1979 to 1984

Business

[edit]- John H. Bryan, '58 – Former CEO of Sara Lee, member of the board of Goldman Sachs, philanthropic driving force behind the creation of Millennium Park in Chicago

Government and military

[edit]

- Thomas Watt Gregory, 1883 – U.S. Attorney General 1914–1919

- Jennings Bailey, 1884 – U.S. District Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia

- William L. Frierson, 1887 – Solicitor General of the United States 1920–21; Assistant U.S. Attorney General 1917–1920

- Key Pittman, 1890 – U.S. Senator from Nevada 1913–40; chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

- Theodore M. Brantley, 1875 – longest-serving Chief Justice of the Montana Supreme Court, serving for 23 years (1899–1922)

- Nathan Lynn Bachman, 1897 – U.S. Senator from Tennessee

- Julian P. Alexander, 1906 – U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi 1918–21; Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Mississippi 1941–1953

- Abe Fortas, '30 – Associate Justice, U.S. Supreme Court (1965–1969); as an attorney, argued Gideon v. Wainwright before the Supreme Court (affirming the Sixth Amendment right to counsel in all criminal cases)

- Gwen Robinson Awsumb, 1937 – American politician and social activist who became the first woman to be elected to the Memphis City Council in 1968; Chair of Memphis City Council 1970–1975

- Joseph Williams Vance, Jr. – United States Navy officer, received Bronze Star Medal for action in the Battle of Makassar Strait (1942) during World War II, attended Southwestern from 1936 to 1938. He later gave his life during the Guadalcanal landings. The U.S. Navy destroyer USS Vance (DE-387), which saw duty in the latter part of World War II, was named in his honor.

- Bill Alexander, '57 – U.S. Congressman from Arkansas (1969–1993), Chief Deputy Majority Whip

- Claudia J. Kennedy, '69 – first woman to hold a three-star rank in the U.S. Army, Lieutenant General, Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, member of the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame

- Amy Coney Barrett, '94 – Associate Justice, U.S. Supreme Court, former U.S. Circuit Court Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit; former Diane and M.O. Miller Research Chair of Law at Notre Dame Law School

- Charles McGrady, '75 – President of the Sierra Club 1998–2000; North Carolina House of Representatives, District 117

- Catherine Eagles, '79 – U.S. District Judge for the Middle District of North Carolina

- Willie Hulon, ‘79 – Executive Assistant Director, National Security Branch of the FBI

- Kelley Paul, '85 – writer, former political consultant; wife of US Senator Rand Paul

- A. Marvin Quattlebaum, Jr., '86 – U.S. Circuit Court Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit

- Alison Lundergan Grimes, '01 – former Secretary of State of Kentucky

- Dustin Burrows, '01 – Texas State Representative, District 83[61]

- Jasmine Crockett, '03 – U.S. Congresswoman for Texas's 30th congressional district

Literature and the arts

[edit]- Verner Moore White, 1884 – Noted landscape and portrait artist; completed commissions for three U.S. Presidents

- Dorothy Jordan, '25 – Stage and film actress; played John Wayne's brother's wife in The Searchers

- Carroll Cloar, '34 – Guggenheim Fellow and artist; one of the South's most highly regarded and widely collected artists

- Peter Matthew Hillsman Taylor, '39 – Pulitzer Prize-winning author

- Marion Keisker, '39 – former Sun Studios employee, first person to record Elvis Presley

- Anne Howard Bailey, '45 – Emmy Award-winning television writer (Adams Chronicles, Bonanza, Lassie)

- Mignon Dunn, '49 – Internationally acclaimed mezzo-soprano, longtime star of New York's Metropolitan Opera

- George Hearn, '56 – two-time Tony Award winning actor and singer; star of Broadway's Sunset Boulevard and La Cage aux Folles

- John Farris, '58 – prolific writer of popular fiction and suspense novels, and stage and screen plays

- Hilton McConnico – artist, designer, and film director; the first American to have work permanently inducted into the Louvre's Decorative Arts collection

- Lara Parker – actress, known for Dark Shadows and Save the Tiger

- Allen Reynolds, '60 – record producer and songwriter,[62] inducted to Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame

- David Ramsey, '61 – music professor, Memphis Redbirds organist for 36 seasons

- Dixie Carter, '62 – Broadway actress and Emmy-nominated television actress, starred in hit CBS sitcom Designing Women

- John Rone, '71 – director, stage actor, former director of college events, former director of the Meeman Center for Lifelong Learning

- Charlaine Harris, '73 – New York Times best selling writer of The Southern Vampire Mysteries series, which HBO later adapted for its series True Blood

- Bill Mobley, '76 – American jazz trumpet and flugelhorn player

- Paul Buchignani, '89 – American drummer, performed on the Afghan Whigs' Black Love album

- Greg Krosnes, '89 – stage actor, voice actor, director

- Sarah Lacy, '99 – technology journalist; former columnist at Bloomberg BusinessWeek and TechCrunch; founder of PandoDaily

Other

[edit]- J. Vernon McGee, '30 – Former pastor of the Church of the Open Door in Los Angeles and founder of Thru the Bible Radio Network.

- Margaret Polk, '43 – former fiancée of the pilot of the Memphis Belle B-17, after whom the plane was named

- Louis Pounders, '96 – American architect, fellow at the American Institute of Architects (FAIA)

- Edward J. Meeman, 1960 – journalist, editor of Memphis Press-Scimitar, namesake of Meeman Center for Lifelong Learning[63]

- Malcolm Forbes, 1983 – editor of Forbes Magazine[64]

- William R. Ferris, 1997 – head of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, co-edited Encyclopedia of Southern Culture

- Isaac Tigrett, 1997 – founder of Hard Rock Cafe and House of Blues[65]

- Peter C. Doherty, 1998 – Australian veterinary surgeon and researcher[66]

- Priscilla Presley, 1998 – American actress and businesswoman, former wife of Elvis Presley[67]

- Bill Frist, 1999 – American physician, businessman, and politician[68]

- Joseph R. Hyde, III, 1999 – founder of AutoZone, part-owner of the Memphis Grizzlies, founder of Hyde Family Foundation[69]

- Cary Fowler, 2011 – American agriculturalist and the former executive director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, attended the school 1967–1969 before transferring

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Historical Timeline". www.rhodes.edu. Rhodes College. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ As of Spring 2023. Rhodes College 2022-2023 Catalog (PDF) (Report). Rhodes College. 2023. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, W. Raymond (1949). Southwestern at Memphis 1848–1948. Richmond, VA: John Knox Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Wood, Bennett (1998). Rhodes 150: A Sesquicentennial Yearbook. Little Rock, Arkansas: August House Publishers, Inc. pp. 28, 41–42. ISBN 0-87483-538-0.

- ^ Staff (ndg) "College History" Rhodes College website

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nelson, Michael (1996). Celebrating the Humanities: A Half-Century of the Search Course at Rhodes College. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-8265-1282-8.

- ^ Michael Nelson. "Rhodes College". Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ wallacen (2015-01-04). "What Others Say About Rhodes". Rhodes College. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ clasm-17 (2015-07-26). "Majors & Minors". Rhodes College. Archived from the original on 2017-12-26. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Troutt leaves legacy of service, focus on diversity at Rhodes College". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ "The Inauguration of the 20th President of Rhodes College". Rhodes College. 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ "President Hass Called to National Leadership Role and Will Leave Rhodes to Become President of the Council of Independent Colleges". Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ "Jennifer M. Collins, President-elect of Rhodes College". Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- ^ a b c d e "About Rhodes". Rhodes College. 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ "Rhodes College". Forbes. Retrieved 2018-03-20.

- ^ a b clasm-17 (2015-07-26). "Majors & Minors". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ clasm-17 (2015-07-31). "Graduate Studies". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rhodes College". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ a b hubmt-18 (2015-10-06). "Foundations Curriculum". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Rhodes College – Colleges That Change Lives". ctcl.org. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ Franek, Robert et al., The Best 361 Colleges: the Smart Student's Guide to Colleges, Random House, Inc., New York, 2006, p. 424.

- ^ a b c woodmanseek (2015-01-04). "Outcomes". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ^ Pope, Loren, Colleges that Change Lives: 40 Schools That Will Change the Way You Think About Colleges, Penguin Books, New York, 2006, p. 185.

- ^ "George Washington Early Selection Program | Health Professions Advising". sites.rhodes.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-12-28. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ a b c d hicae-16 (2015-07-30). "Community Service". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rhodes Vision". Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ wallacen (2015-01-04). "What Others Say About Rhodes". Rhodes College. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ^ clasm-17 (2015-07-30). "St. Jude Summer Plus Fellowship". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ clasm-17 (2015-07-30). "Rhodes/UT Neuroscience Research Fellowship". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b clasm-17 (2016-08-04). "Buckman International Internship Program". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ clasm-17 (2015-07-30). "Internships". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ troma-17 (2015-08-07). "Study in Washington, D.C." Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Study Abroad and Away". Rhodes College. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "New Study Abroad Policy Will Help More Rhodes Students Experience the World | Rhodes News". news.rhodes.edu. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ a b clasm-17 (2016-01-12). "Mike Curb Institute for Music". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b filesj (2016-01-14). "The Audubon Sessions". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ^ a b "At Home With Elvis: King's first house now concert home for students and fans". Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ^ "Nelson: How to fight recidivism with great books". The Daily Memphian. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ a b "Foundations Programs in the Humanities | Catalogue". catalog.rhodes.edu. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

- ^ as in Turner South's Blue Ribbon, Princeton Review, Collegiate Gothic: The Architecture of Rhodes College by William Stroud, and other sources

- ^ "Rhodes Recognized". Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ "Rhodes Arboretum". Rhodes College. 2017-09-27. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ^ a b c Morgan, William (1989). Collegiate Gothic: The Architecture of Rhodes College. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-82620699-9.

- ^ "Filming locations for Making the Grade". IMDb. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Halliburton Tower in the snow around 1994". 1994.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ These figures are published in the Rhodes College Common Data Set Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ clasm-17 (2015-08-04). "International Studies". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ morjc-17 (2015-01-04). "Our Traditions". Rhodes College. Retrieved 2017-12-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Rhodes wins first team championship since 1961; Lynx never trailed". NCAA. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "NCAA Women's Golf: Rhodes College wins second straight championship". NCAA. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Sports Illustrated Magazine Recognizes Rhodes-Sewanee Football Rivalry". Southern Athletic Association. 2012-08-20. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ Churchill, John (2012-08-20). "More Than a Game". Memphis Flyer. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ "About Our Team". Rhodes College. Archived from the original on 2015-02-25. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "National Championship Trial Results". Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ "Robert Penn Warren Biography". Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (2001). "Ming Dong Gu".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "David Alexander (1932–2010)". Archived from the original on 2014-10-20. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "Byerley appointed Vice Dean for Education". Vital Signs. UNC Health Care News. 2013-09-12. Archived from the original on 2015-04-17. Retrieved 2015-04-13.

- ^ "Dr. Bryan Coker named 12th president of Maryville College". February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ "About Dustin Burrows - Candidate for Texas House District 83 Representative". Archived from the original on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2014-11-05.

- ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (2000). "Reynolds was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2000".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1960). "Edward J. Meeman receiving an honorary degree".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1983). "Malcolm Forbes, Editor of Forbes Magazine, spoke to the 239 members of the graduating class at commencement and received an Honorary doctor of humanities".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (May 1997). "Isaac Tigrett".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1998). "Peter Doherty received an honorary degree in 1998".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1998). "Priscilla Presley".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1999). "Frist received an honorary doctorate at Rhodes' commencement ceremony in 1999".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rhodes College Digital Archives (1999). "Mr. Hyde was recipient of an honorary doctor of humanities at Rhodes' commencement ceremony in 1999".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

External links

[edit]- Rhodes College

- Universities and colleges in Memphis, Tennessee

- Liberal arts colleges in Tennessee

- Private universities and colleges in Tennessee

- Universities and colleges affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (USA)

- Universities and colleges accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

- Universities and colleges established in 1848

- 1848 establishments in Tennessee

- Collegiate Gothic architecture in the United States