Peritrope

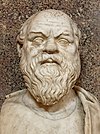

Peritrope (Greek: περιτροπή) is Socrates' argument against Protagoras' view of subjective truth, as presented in Plato's book known as Theaetetus (169–171e). This formed part of the former's eighth objection, the "table-turning" argument that maintained Protagoras' doctrine was self-refuting.[1] Peritrope – as the basic objection – has also been used by Greek philosophical commentators as well as modern philosophers.[2]

Overview

[edit]The term itself came from an ancient Greek word that means "a turning back on one" and likened to the image of a snake devouring its own tail.[3] Socrates' peritrope described Protagoras' view as a theory that no longer requires criticism because it already devours itself.[3] Sextus Empiricus is thought to have given the name in a comment on Protagoras' view in Against the Logicians[4] written around 200 CE.[5] The name has been in continuous use ever since, as Socrates' argument provides the foundation for classical propositional logic and hence much of traditional western philosophy (or analytic philosophy). For instance, Sextus noted that Protagoras' famous doctrine that man is the measure of all things is self-refuting because "one of the things that appears (is judged) to be the case is that not every appearance is true".[6] This assumption was later refuted due to a mistake on the part of Sextus' interpretation that the Protagorean measure doctrine boiled down to a subjectivist thesis that whatever appearance whatsoever is true.[7]

Well-known attestations of peritrope also include Avicenna and Thomas Aquinas, and in modern times Roger Scruton, Myles Burnyeat, and many others. The word is occasionally used to describe argument forms similar in nature to that of Socrates' overturning of Protagoras. Modern philosophers overturning Protagoras' subjective truth include Edmund Husserl and John Anderson.[8]

For many centuries the peritrope was used primarily as a tool for refuting versions of skepticism[9] that propose that truth is unknowable, which can be challenged by responding with the peritrope — the question, Well, then, how do you know that to be true? This kind of skepticism and similar views are considered to be "self-refuting." In other words, a philosopher has retained what he has disavowed in and by the disavowal itself. In general, versions of the peritrope can be used to challenge many kinds of assertion that universality is impossible.

In What Plato Said, Paul Shorey notes: "The first argument advanced by Socrates is the so-called peritrope, to use the later technical term, that the opinion of Protagoras destroys itself, for, if truth is what each man troweth, and the majority of mankind in fact repudiates Protagoras' definition of truth, it is on Protagoras' own pragmatic showing more often false than true".

In Modern Philosophy: An Introduction and Survey (1996), Roger Scruton formulates the argument as such: "A writer who says that there are no truths, or that all truth is 'merely subjective,' is asking you not to believe him. So don't."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chappell, Timothy (2005). Reading Plato's Theaetetus. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. p. 108. ISBN 3896653156.

- ^ Mendelson, Michael (2002). Many Sides: A Protagorean Approach to the Theory, Practice and Pedagogy of Argument. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 19. ISBN 1402004028.

- ^ a b Snare, Francis (2002). The Nature of Moral Thinking. New York: Routledge. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0203003055.

- ^ (389-90).

- ^ Tindale, Christopher W. (2012-09-18). Reason's Dark Champions: Constructive Strategies of Sophistical Argument. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781611172331.

- ^ Burnyeat, M.F. (2012). Explorations in Ancient and Modern Philosophy, Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521750721.

- ^ Carter, J. (2016). Metaepistemology and Relativism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 9781349673759.

- ^ Burnyeat, M. F. (2012). Explorations in Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521750721.

- ^ Fogelin, Robert (1999). Wittgenstein-Arg Philosophers. Oxon: Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 9780415203784.

External links

[edit]- Myles, Fredric Burnyeat (1976). "Protagoras and Self-Refutation in Plato's Theaetetus". The Philosophical Review. 85 (2): 172–195. doi:10.2307/2183729. JSTOR 2183729.

- Chappell, Timothy (2006). "Reading the Peritrope" (.doc). Phronesis.